A critical look at the Digital Markets Act

The European Commission’s proposed Digital Markets Act aims to increase fairness and competition among firms working in the digital space. In doing so, however, it introduces new burdens and could give less enterprising firms the upper hand.

In a nutshell

According to the European Commission, a unique type of firm exerts tremendous control over most digital business models. These behemoths, called “gatekeepers,” organize access and manage upstream and downstream businesses, just as trusts did in their day. Like trusts, these digital companies could bar any noncompliant business from using the internet, stifling competition and economic freedom. For all these reasons, the Commission felt compelled to propose a new regulation, the Digital Markets Act, or DMA.

As of this writing, the DMA remains only a proposal. It still needs consultation and political approval. However, in the EU, such legislation is often passed with few amendments. It is styled as a separate and complementary tool for competition enforcers, introducing new policy objectives of “fairness and contestability.”

Regulations for gatekeepers

The DMA introduces the notions of “digital sector” and “gatekeeper.” While the very idea of a “digital sector” is already difficult to grasp, the concept of “gatekeepers” is altogether foreign to antitrust practices. The DMA describes them as “structuring elements” of the digital economy that enjoy an entrenched position in providing intermediation services. Network effects help make users (businesses and individuals alike) dependent on these gatekeepers. According to the DMA, this dependence allows them to engage in unfair practices and harm consumer welfare. Therefore, gatekeepers have a major impact on digital markets and require oversight.

The provisions regulate gatekeepers instead of taking the standard antitrust approach.

The DMA’s provisions apply to all gatekeepers and are applicable “ex ante” (see box). That means these provisions regulate gatekeepers instead of taking the standard antitrust approach of remedying any harmful market behavior in which they might engage.

Facts & figures

Ex ante vs. ex post regulation

Normally, regulatory action occurs after a market failure or distortion. This is “ex post” regulation. It always takes place once information is already available and sufficient evidence is presented to prove negative consequences. Sometimes, however, authorities aim to identify problems before they occur. This is ex ante regulation – it is predictive and prone to the regulators’ bias. In other words, ex ante regulation tells market actors what to do, whereas ex post regulation tells them what not to do.

Source: ECIPE.org

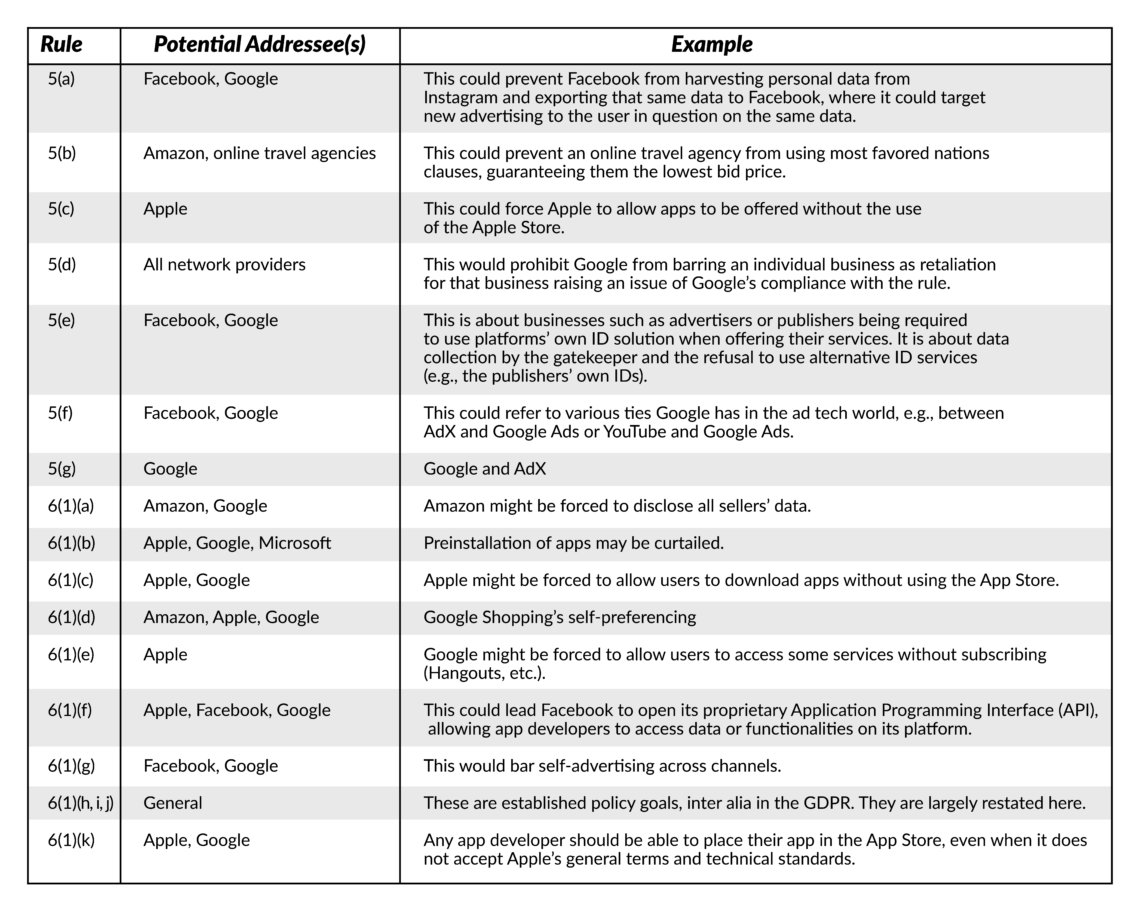

Under the DMA, gatekeepers’ main obligation is to allow all other market actors to use the platforms they maintain without discrimination and without tying in other services. Gatekeepers are barred from self-preferencing their other services, combining data collected from two or more of their own services, and self- or cross-advertising among channels. A more extensive list of regulations and possible applications is summarized in the table below.

Facts & figures

Digital sector

An underlying premise of the DMA is that digital markets can be separated from nondigital markets for purposes of applying regulatory requirements. However, digital technologies are increasingly transforming many industries – not just internet platforms. In various “traditional” sectors of the economy, firms compete to reach users and consumers through multiple business channels, including digital ones. Also, individual businesses are increasingly adopting digital tools to plan and produce goods, extract value from data, branch out into new markets and update their strategies.

In short, business models are incorporating digital tools. This transformation is occurring across sectors, activities and business cases, meaning digital technology appears in multiple combinations throughout the economy. By the EU’s legal line of thought, then, everything is digital. But if everything is digital, what is the value or even the sense of regulating the digital realm separately

Digital and nondigital channels are intertwined. Separating them is impossible.

Even if the focus is restricted to a narrow view of digital services, these almost always filter down into nondigital services, tangible goods or infrastructure. For example, while Uber is an application, it relies on millions of “real-world” people, cars and streets. It combines these with other digital services, like payment and routing, which are themselves dependent on several nondigital elements. Digital and nondigital channels are intertwined. Separating them is practically impossible.

When narrowing the scope even more by concentrating only on markets, the DMA’s distinction cannot hold. Within a given industry, digital and analog agents compete to reach end users through distinct means with their own particular costs and benefits.

For example, when Amazon decided to sell books on the internet, it did not create a new market in the digital space. Even in selling online, it competed against all other bookstores in brick-and-mortar locations, organizations selling books in print catalogs, and many more. Assuming Amazon is the only online retailer of books but has no more than a 30 percent share of the total global market, would that make it a monopoly in the digital market? The answer is no, because there is no such thing as an online book market that is distinct from the offline book market. The only relevant market for antitrust purposes is the product market, encompassing both the online and offline distribution channels.

Curtailing gatekeepers

The DMA could hinder the widespread adoption of digital technologies. First, it creates extra regulatory costs that could undermine the competitiveness of businesses acting in the digital space. Just as the effects of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) have benefited large tech firms and hurt other companies, the DMA creates extra regulatory costs that raise barriers to entry, thereby preserving the incumbents’ positions.

The DMA could also slow down digital innovation. Reducing digital businesses’ competitiveness compared to their nondigital counterparts deters digital transformation, slowing down or even preventing disruption. The obligation to share data with and grant access to rivals makes it cheaper (if not free) for firms to copy market leaders’ moves. Imitation becomes more attractive than innovation.

In other words, innovation laggards benefit from the regulation, enabling them to imitate the leaders, which are themselves deterred from innovating. Requiring access to rivals gives them a decisive strategic advantage through regulation – at no cost.

This risk of free-riding appears in the DMA in multiple instances. For example, it states that the gatekeepers should ensure access under similar conditions to, and guarantee interoperability with, the same operating system, hardware or software features that are available or used in the provision of any ancillary services by the gatekeeper. This overlooks innovation resulting from the incentive to design an operating system with proprietary services attached to it.

Furthermore, the DMA creates a skewed playing field against digital channels and companies identified as gatekeepers. The key to understanding this is recognizing the DMA’s focus on increasing the “contestability” of core platform services rather than digital markets. This focus suggests that the EC designed the regulation explicitly to uproot the gatekeepers’ market positions in favor of other companies. It is therefore wrong to assume that the current gatekeepers enjoy “unassailable” market positions. The DMA would help other companies replace them.

None of this offers clear benefits to consumer welfare or innovation, especially if the firms that replace the incumbents provide inferior services. In fact, it encourages rent-seeking, free-riding behaviors at the expense of incentives to innovate. The DMA’s bias seems aimed not against unfair practices, but against the “gatekeeper” firms themselves.

The DMA would encourage free-riding behaviors at the expense of innovation.

Finally, the DMA pushes antitrust activity into the regulatory realm. Competition law assumes that market processes are self-regulating, and only steps in if they produce outcomes that are detrimental to competition. However, the DMA assumes that the digital gatekeepers, if left to their own devices, do not act according to competitive market processes and must be directed before entering those markets. The gatekeepers bear the cost by having to conform with all the requirements stipulated by the antitrust authority-turned-regulator.

In focusing on gatekeepers in digital markets, the DMA does away with various antitrust safeguards. Prioritizing the interests of competitors, suppliers and users of digital platforms, the DMA regulates gatekeepers’ activities and prices. It does not even allow the EC to modify the obligations it imposes if they prove counterproductive or harmful. This lack of a safety valve is particularly troubling since much of what the DMA prohibits actually creates value for consumers. While the EC has assumed that the DMA will produce positive outcomes, it is difficult to predict the real economic effects of its many prohibitions and rules.

Scenarios

The DMA replaces economically sound, effects-driven antitrust law with regulation based on bad economics and suspicious modeling. The act could slow the adoption of digital technologies among European companies for three main reasons:

First, increasing regulatory costs are likely to drive up barriers to entry, thereby reinforcing rigidity in the economy and in companies themselves. The DMA will suppress incentives for small and medium-sized platforms to innovate and scale up. Growth and success will be met with increased regulatory scrutiny, possible legal liability and an inability to claim the profits brought by innovation.

Second, the DMA’s regulatory proposals will reduce incentives for large online platforms to provide innovative products and services to European businesses and consumers. Restrictions on gatekeepers, including prohibitions on bundling and adjacent market entry, would directly hinder platforms’ ability to develop new products and services for customers. Companies that are close to meeting gatekeeper status may be discouraged from creating new services that would bring in additional users.

For example, the rules could dissuade a large platform provider from investing in a new telehealth channel, for fear of outgrowing its established regulatory category. DMA restrictions will keep existing gatekeepers from constraining each other through competition, particularly outside of their own area of specialization. Examples could include Apple introducing search functions or Microsoft offering digital advertising services.

Finally, as large online platforms are constrained, opportunities for natural affiliations between less-digitized European firms and highly digitized American firms will dwindle.