A test for China-NATO strategic restraint in the Indo-Pacific

A UK-led carrier strike group will be present on China’s maritime doorstep on the centenary of China’s communist party. The West means to show unity in response to Beijing’s disruptive global posture. Chinese leadership could resort to several options to show its displeasure.

In a nutshell

- The UK has dispatched a strong naval group to waters claimed by China

- The intention is to show Western resolve in confronting Beijing’s policies

- China may respond with further militarization of the South China Sea

Soon, the United Kingdom Carrier Strike Group 21 (CSG21), led by the Royal Navy’s most potent ship, the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, will pass the Malacca Straits and enter the South China Sea. The British government has heralded the deployment as an important element of the post-Brexit “Global Britain” campaign and a powerful tool in support of international rules-based order.

The UK’s reasoning behind an inaugural operational deployment to the Indo-Pacific has been set out in a recent defense and security white paper. In what it describes as a “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific, London has acknowledged that the region’s stability is of crucial importance to global economic vibrancy. It also warns of the increasingly potent military challenge posed by China in the area and, for the first time, the need to stand up to Beijing’s coercive behaviors. This analysis echoes the bipartisan sentiment in Washington. For this reason, the mission has been choreographed not only as a joint UK-United States deployment but also as a power projection drive by NATO in the Indo-Pacific region.

The carrier is host to a detachment of 10 U.S. Marine F-35B stealth fighters and will be escorted by a Dutch frigate HNLMS Evertsen and the U.S. destroyer USS The Sullivans. The timing of the CSG21’s arrival in the South China Sea, much of it claimed by China as its territory, comes at a particularly sensitive moment for Beijing, as the Chinese Communist Party celebrates its centenary.

NATO vs. China

Recent Group of Seven (G7) and NATO statements have incensed Beijing. In a joint statement, G7 leaders condemned human rights abuses against China’s Uighur population in Xinjiang, expressed deep concern over the erosion of freedom in Hong Kong and for the first time also stressed the importance of the stability of the Taiwan Strait. All three issues are what China describes as “core concerns” – strictly internal affairs and off-limits to foreign interference.

NATO leaders asserted that China increasingly endangers the security of Western democracies.

G7 members also rallied behind Australia, whose relations with Beijing remain strained. In the margins of the G7 summit, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison revealed that the Royal Australian Navy would be dispatching two frigates for joint exercises with the British-American group. In a subsequent speech to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris, Mr. Morrison called for global cooperation to ensure peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific, blaming China for undermining the rule of law and threatening the world order. French Prime Minister Emmanuel Macron emphasized France’s commitment to defending, in partnership with Australia, the balance in the Indo-Pacific region against coercion and intimidation.

The NATO summit immediately after the G7 was even more direct. Celebrating renewed unity of vision, NATO leaders asserted that China increasingly endangers the security of Western democracies. Highlighting concerns over China’s expanding nuclear arsenal, enhanced cooperation with Russia and Chinese disinformation campaigns, they observed that “China’s stated ambitions and assertive behavior present systemic challenges to the rules-based international order and areas relevant to Alliance security.” Another statement read that Beijing’s coercive policies run contrary to the values enshrined in the Washington Treaty, NATO’s founding charter.

Before and shortly after the CSG21’s deployment to the Mediterranean for joint exercises, British and NATO leaders have barely concealed the message intended for China. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, visiting the carrier on May 21, observed that the voyage would show China that the UK believes in the law of the sea. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg paid a visit to the carrier during exercises off Portugal to state that the alliance was facing global threats and challenges, including the shifting balance of power with the rise of China. “She carries U.S. Marines, she is protected by a Dutch frigate, and she is on her way to the Pacific,” the secretary said. Commodore Steve Moorhouse, the CSG21 commanding officer, added that the aim of the voyage was to uphold international norms in the Indo-Pacific.

Angry words, calculated steps

China reacted with predictable vitriol. In response to the G7 communique, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said that the U.S. was “sick” and that the G7 should “feel its pulse and prescribe medicine for it.” Of NATO, he stated that the alliance had brought wars and instability to the world. He also claimed that NATO owed a debt of blood to the Chinese people, who would never forget the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia. A popular digital artist in China probably best summed up Chinese sentiment when he lampooned G7 members, plus Australia and India, as animal characters assembled at a Last Supper table with an American Bald Eagle representing Jesus. The parody went instantly viral in China.

The plan would be modeled on NATO’s Standing Naval Forces Atlantic framework during the Cold War.

Further fueling Beijing’s ire and confirming NATO’s determination are reports coming from Washington. The Pentagon’s China Task Force is said to be putting the final touches on creating a Pacific region “Permanent Naval Task Force” to counter China’s rapidly advancing military capability. The task force would be given a named military designation in the West Pacific. The arrangement would allow the U.S. secretary of defense to channel funding directly into ways to address military challenges from China. Intriguingly, reports suggest that the plan would be modeled on NATO’s Standing Naval Forces Atlantic framework during the Cold War.

The plan would allow for NATO naval assets to be attached to the force for months at a time, creating a rapid reaction capability during times of escalation but also undertaking port calls and military diplomacy. This closely resembles the mission goals of CSG21: the UK’s aim to offer a regularized deployment to the Indo-Pacific, and the Biden administration’s goals of coalition building to serve as a force multiplier to counter China’s rogue policies.

Meanwhile, the USS Ronald Reagan, a Nimitz-class, nuclear-powered supercarrier on route to the Indian Ocean to assist in securing the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan, has conducted maritime strike exercises in the South China Sea. Its commander also revealed that one of the group’s destroyers had worked alongside an Australian frigate to ensure that all nations continue to benefit from a free and open Indo-Pacific region. A key component of the U.S. Free and Open Indo-Pacific policy is Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs). The U.S. Navy exercises the right to the free passage of its vessels in international waters. In the South China Sea, this in practice means the transit of navy vessels within 12 nautical miles of areas claimed by China, sometimes close to Chinese military bases.

Since 2015, the U.S. Navy has undertaken over 30 FONOPs in the area, sometimes encountering dangerous maneuvers by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). The British Royal Navy has launched similar operations there. For example, HMS Albion, an amphibious assault ship, passed through the disputed Paracel Islands in response to China’s excessive maritime claims in 2018, attracting a furious response from Beijing. This time around, it remains unsaid whether elements of the CSG21 will undertake U.S.-style FONOPs. That could trigger a military response from the Chinese. Experts have already drawn comparisons with a recent FONOP conducted by Royal Navy destroyer HMS Defender off the Crimean peninsula, prompting a hostile response by Russia’s security forces.

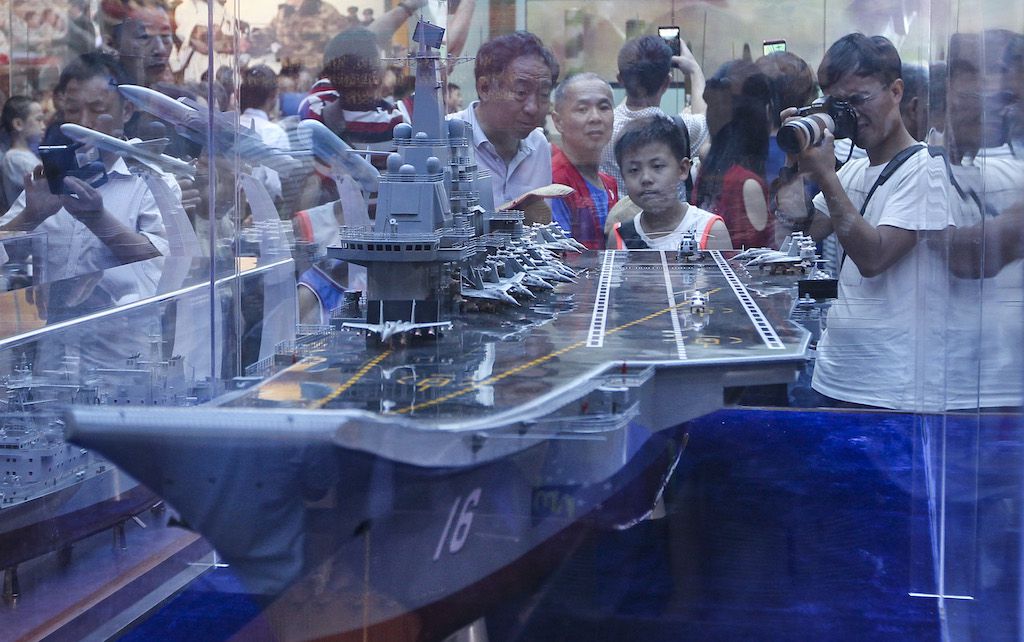

The Great Wall of Sand

On 23 April, Xi Jinping, in his capacity as Chairman of China’s Central Military Commission, presided over the commissioning of three warships amounting to 60,000 tons of new Chinese naval power at the Yulin Naval Base in Hainan. The new vessels include Hainan, China’s first Type 075 amphibious helicopter carrier; Dalian, Type 055 guided-missile cruiser; and Type 094 (Jin-class) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine Changzheng-18. The PLA has recently increased the pace and scale of its military deployments across the South China Sea, indicating a willingness to push back against the imminent arrival of the Western carrier group there.

This heightened readiness of Chinese forces across the region may indicate Beijing’s confidence in its new military bases built on reclaimed atolls in the disputed waters of the Spratly Islands. A decade ago, China embarked on spending billions of dollars to construct state-of-the-art military outposts at the heart of the South China Sea. Reclaiming several pristine atolls in the Spratlys, some of them within the Exclusive Economic Zones of other claimant states, Chinese dredging vessels disgorged billions of tons of sand on top of shattered reefs creating artificial islands.

Defense experts speculate about the utility of the artificial islands.

It became rapidly evident from satellite imagery that these islands would be turned into sophisticated naval and air bases, prompting then U.S. Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Harry B. Harris Jr. to decry the construction by China of a “Great Wall of Sand” in the sea. In the intervening time, the bases have served as a forward capability for the saturation of the region by China and an extension of Chinese command, control, communications, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities.

Not only has the PLA Navy established and regularized its deployments at these bases, but the rapidly expanding tonnage of the Chinese Coast Guard has also poured into the Spratly Islands. Finally, China’s “blue hull” fleet, the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia, has sustained assertive activities across the region. Masquerading as a fishing fleet, its vessels use “swarming” techniques to maintain a Chinese presence within numerous disputed atolls of the Spratly Islands. In March 2021, the Maritime Militia stationed about 200 vessels in Whitsun Reef, a feature also claimed by Vietnam and the Philippines, prompting outrage in Manila and Philippines Foreign Affairs Secretary Teodor Locsin to lose his composure with Beijing on Twitter.

In early June, a formation of 16 PLA Air Force transport aircraft overflew their bases in the Spratlys and bore down toward Malaysian airspace off Borneo, ignoring repeated attempts at radio contact by civilian air traffic controllers. The Royal Malaysian Air Force scrambled fighter interceptors and Kuala Lumpur lodged rare diplomatic protests with Beijing. Even more recently, early warning and electronic warfare aircraft and a Type-815G intelligence-gathering ship have been spotted at Fiery Cross Reef, one of the PLA bases at the edge of the Spratlys.

Scenarios

One of the missing components of China’s militarization of the Spratlys has been the deployment of fighter jet and bomber detachments to the bases – the reinforced military hangars have apparently remained empty. Defense experts speculate about the utility of the artificial islands. Some find them inherently vulnerable and exposed – U.S. strategic bombers or guided missiles could rapidly reduce them to coral rubble in a high-intensity conflict. Others have questioned the strategic utility of the bases as a defensive line, a kind of maritime Maginot Line. However, China’s goal seems to have been to exploit the latency of the bases in a sub-conflict environment, also stressing the civilian dual utility of the islands for search and rescue, navigation safety, maritime domain awareness, and fisheries management.

One of the options available to the PLA now is to announce the closure of large tracts of sea space to conduct military exercises. Perhaps the most provocative exercises on the menu of options for the PLA could be live ballistic missile tests into portions of the South China Sea timed with the arrival of the NATO ships. As displayed at recent military parades, China’s strategic rocket force boasts mid-range, precision-guided “carrier killer” missiles, including the Dongfeng 21-D, fired from China’s mainland and designed to target individual vessels at sea with multiple warheads. But perhaps the obvious option for Beijing is to deploy one of its own new carrier strike groups to the area and possibly land fighter jets on its bases in celebration of its 100th birthday.

On July 1, China’s Communist Party celebrated its centenary amid great fanfare in Beijing. The event featured a large military parade. The presence of a robust foreign naval force under NATO auspices in its backyard has been a major irritant and may compel Beijing to mount its own show of strength there. Over several months, the South China Sea has once again become increasingly militarized despite recent calls for restraint by ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers.

There are numerous options for China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to demonstrate Xi Jinping’s displeasure with the appearance of the NATO aircraft carrier group on China’s maritime doorstep. All of them ramp up the potential for military escalation.

As the CSG21 undertakes joint exercises and port calls with friends and allies, the next two months will serve as a litmus test for strategic restraint in the Indo-Pacific.