Australia’s green energy potential

Fossil fuels are a significant part of the Australian economy, but the country is now taking big strides toward renewable solutions. Green energy from Australia has the potential and the materials to become a major global supplier – despite growing spats with China.

In a nutshell

- Fossil fuels play a big role in Australia’s economy

- Australia's green energy sector has promising potential

- Its wrangling with China poses a significant challenge

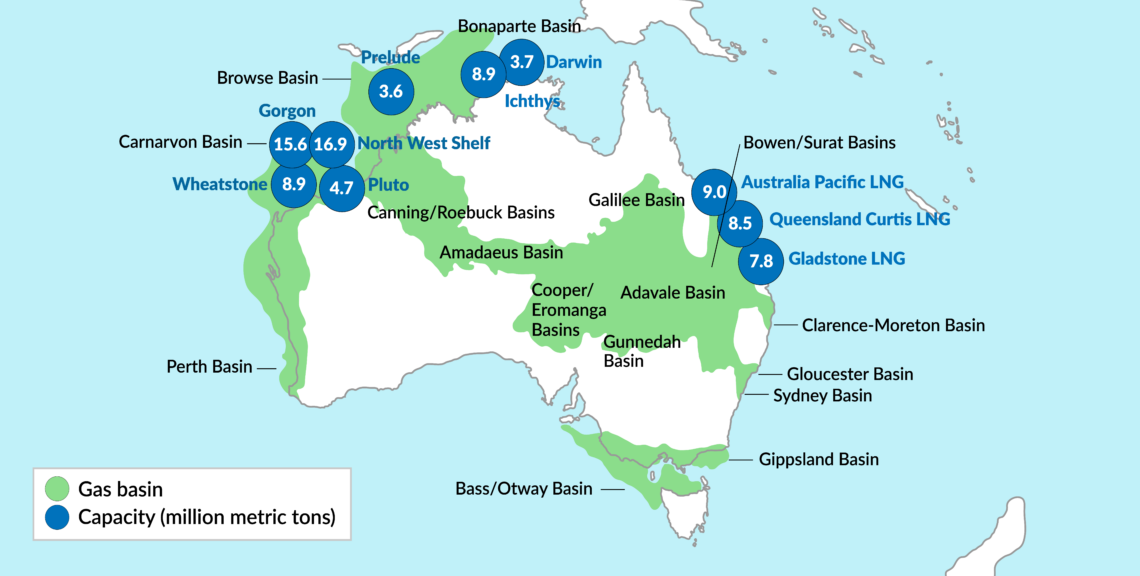

Australia is one of the few rich Western countries with significant net energy exports. It sells more than 60 percent of its overall energy production abroad in the form of coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG). In 2020, Australia was the world’s second-largest LNG exporter, after Qatar.

Yet Australia also has the potential to become a critical player in the production of environmentally friendly, or “green” energy. Eventually, it could be one of the world’s largest exporters of hydrogen and the critical raw materials (CRMs) needed for the global expansion of renewable energy, decarbonization and digitization technologies. It already sells an enormous amount of resources abroad. Iron ore and coal alone account for about a third of its total exports. It is also an important supplier of CRMs to Western countries.

The country holds the world’s largest proved recoverable reserves of uranium (some 30 percent) and is the third-largest producer of the resource (about 21 percent of global production in 2019). Nevertheless, it does not have any nuclear power plants.

In 2019, fossil fuels still made up almost 90 percent of Australia’s energy supply and 79 percent of its electricity generation. Some 60 percent of its power comes from coal. It has taken steps to change this situation, investing AUD 31 billion ($23.66 billion) since 2017 on renewable energy, which now accounts for about 20 percent of electricity supply. Nevertheless, the country faces an energy and climate crisis with major foreign policy and geopolitical implications.

Facts & figures

Export powerhouse

Australia is a leading exporter of raw materials. It is the world’s largest exporter of iron ore and coking coal. It is the world’s largest producer of bauxite, a source of aluminum (of which Australia is the fifth-biggest producer). It is also the world’s fifth-largest producer of copper and cobalt. It has the second-largest reserves of copper, cobalt and bauxite, and the third-largest reserves of lithium and rare-earth minerals.

Looming crises

Australia suffers from frequent electricity outages because of insufficient policy coordination between federal and state authorities, a lack of federal government control over onshore gas fields (which fall under the jurisdiction of state or territorial governments), as well as infrastructure issues like weak transmission, interconnector failure and lack of storage. Prices are among the highest in the world, burdening households and businesses. This unreliability in supply threatens to cripple the country’s large, energy-intensive industrial sector.

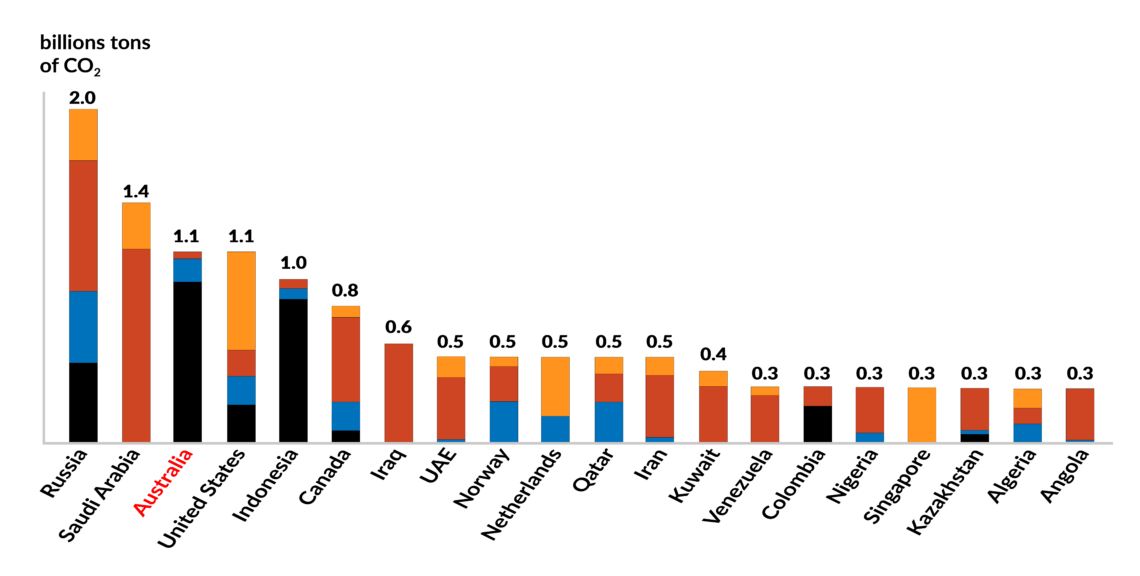

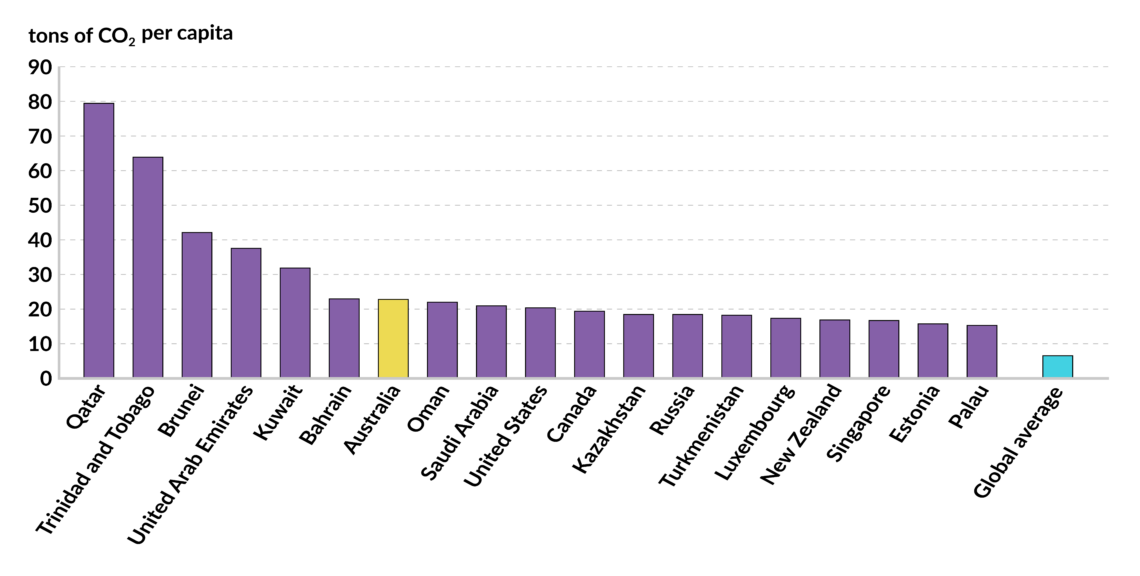

Per capita, Australia is one of the biggest carbon emitters in the developed world.

Although Australia is a major LNG exporter, it also faces a long-term gas crisis. The eastern parts of the country risk supply shortfalls by 2025 due to the aging gas fields in the Bass Strait and in the Gippsland and Otway Basins, which are depleting faster than expected. New plans for a long-distance transcontinental pipeline do not appear commercially viable, since liquefying and shipping gas is often a lower-cost option. The government has therefore favored LNG and Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRU) moored at Port Kembla and other harbors in New South Wales.

The government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison is promoting gas projects to help the economy recover from the downturn brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. But since Australia’s gas reserves are only the 14th largest in the world, (1.2 percent of the global total), a long-term transition period based on natural gas appears unlikely.

Facts & figures

Australia’s carbon emissions from electricity generation (per kilowatt-hour) are nearly twice those of the United States. Per capita, the country is one of the biggest emitters in the developed world. Although it accounts for just 1.3 percent of global carbon emissions, its share would rise to 4 or 5 percent if one were to include the burning of the coal it sells abroad. The CO2 emissions from its fossil fuels exports are the third highest in the world.

Climate change has severely affected Australia’s environment. In recent years it has experienced disastrous fires, water shortages and record high temperatures. Wildfires in 2019-2020 alone burned through some 18 million hectares, causing an ecological disaster. The country’s government has accepted that global warming is a major factor behind these phenomena, offering hope that its energy and climate policies will now produce a growing political consensus after a decade of disunity over the issue.

Facts & figures

A green superpower

Australia’s green energy sector is growing rapidly with significant potential. It plans a huge increase in distributed energy – that is, generating electricity from renewable resources in a disbursed manner, from homes and businesses, rather than from big, centralized power plants. This type of production is becoming cheaper to implement. By 2040, the country wants to generate 94 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. According to its road map, coal and gas power plants will not keep running past their currently scheduled retirement dates, and some may even shut down earlier.

The country’s conservative government had previously taken a skeptical tack toward green energy, but now, backed by powerful investors, it is pushing a renewable energy-based export industry to help hasten its transition toward decarbonization and diversify its economy. The latter will be crucial in the eventual absence of the coal industry, which contributes some $42 billion a year to the Australian economy.

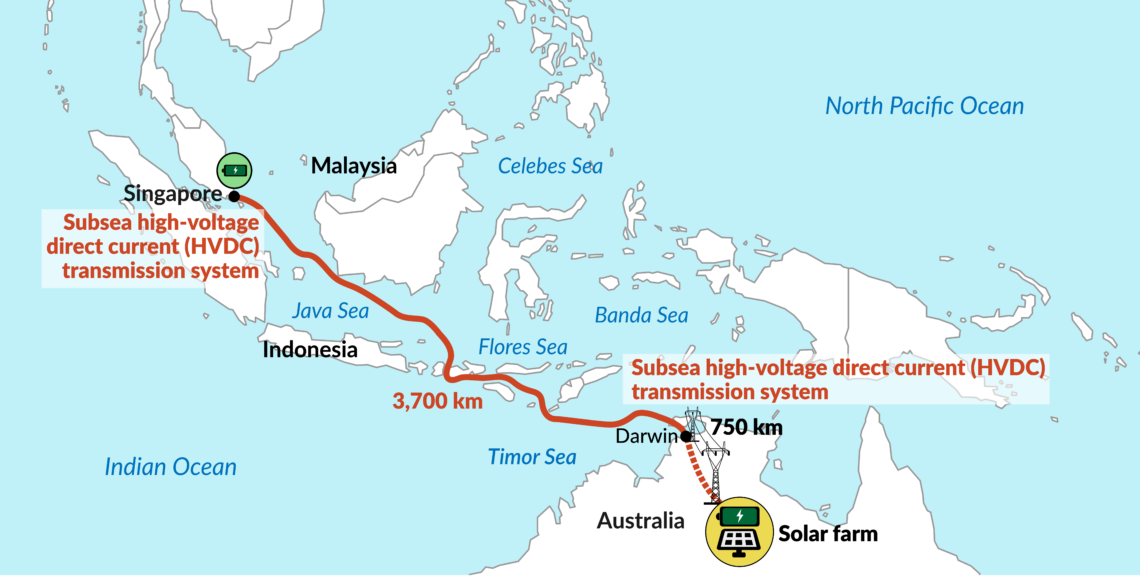

Australia will soon host the world’s “biggest battery,” a 700-megawatt energy storage facility in New South Wales, as well as what is being billed as the world’s largest solar farm, in the Northern Territory. The latter will produce electricity for a 3,700-kilometer high-voltage direct current (HVDC) undersea cable that by 2027 will run at depths of up to 1,700 meters across the Timor, Flores and Java Seas to Singapore, supplying that country with $1.5 billion worth of green energy.

By 2050, global production of CRMs could increase by 500 percent.

Solar and wind power capacity per capita is due to increase at a rate five times faster than in the European Union, U.S. or China. The planned Asian Renewable Energy Hub in Western Australia will be the world’s largest combined solar and wind farm, and aims to generate 26,000 megawatts. Not only will it offer power generation, it will also produce hydrogen that can be used to power vehicles and make ammonia for fertilizers and pharmaceuticals. National Energy Resources Australia (NERA) has just unveiled a network of 13 regional hydrogen technology clusters across the country.

Australia has enormous potential to enhance its energy efficiency. A lack of policy solutions and targeted programs in the past has made it one of the least-efficient energy users in the world. A recent ranking placed it 18 out of the world’s top 25 biggest energy consumers, based on 36 efficiency measures.

Optimal conditions

According to a May 2020 World Bank report, by 2050 global production of CRMs such as lithium and cobalt could increase by 500 percent. Preventing global temperatures from rising by more than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels (a threshold most climate scientists agree would result in catastrophic effects if crossed) would require some 3 billion tons of CRMs for the appropriate wind, solar and geothermal technologies. With its plentiful CRM resources, Australia’s geopolitical significance could grow.

And while countries like Australia, Canada, the U.S. and Chile have more restrictive mining regulations, they are also more predictable, less corrupt and more investor-friendly than most developing countries with CRM reserves. They are therefore expected to see the bulk of CRM-related investment in the coming years. Australian mining companies, with their expertise, advanced technology and ability to innovate, have already built up a positive reputation and a world-class industry.

All this means that Australia could become a crucial supplier of CRMs, as the U.S., Europe, Japan and India all seek to reduce their dependence on China. Its optimal conditions for solar and wind power, and its huge swaths of unpopulated territory, also make it an ideal place for projects like the Asian Renewable Energy Hub mentioned above, and therefore a dominant hydrogen exporter.

Hampered by China

In recent decades, Australia has benefited greatly from China’s economic rise, as its exports of fossil fuels, raw materials and agricultural products (including beef, barley and wine) shot up. In 2019, China accounted for some 38 percent of Australia’s exports. Since 2008, Chinese companies have invested more than $100 billion in Australia. China depends on Australia for 61 percent of its iron ore, 53 percent of its coal and 23 percent of its thermal coal.

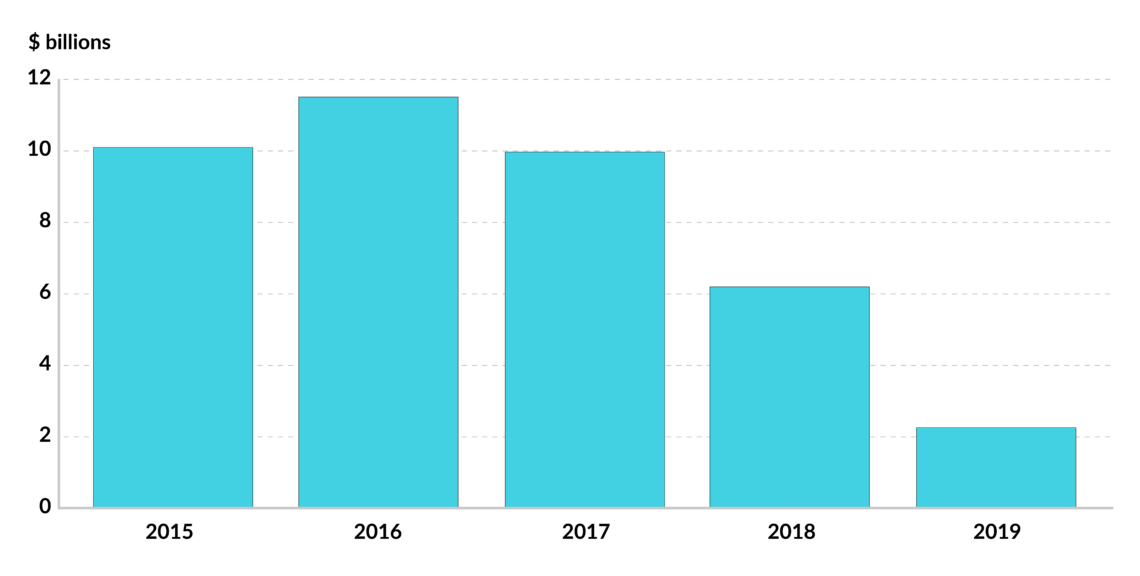

China is Australia’s biggest trade partner – the exchange was worth some $190 billion in 2019, and the recent rapid deterioration in relations between the two countries has hit the latter hard. In the same year, Chinese investment in Australia declined to its lowest level in a decade. It is not just Chinese companies that are less keen to invest in Australia. Canberra has also tightened its foreign investment screening, and officials see Chinese investors as presenting a higher strategic risk.

Facts & figures

In 2020, Beijing restricted coal imports from Australia. China is relatively self-sufficient in coking coal (used to make steel) with 80 percent of its consumption coming from domestic mines. Yet it still needs to import more than 70 million tons a year. Officially, China said it had implemented the severe curbs on coal imports because they had failed to meet environmental standards. Australian coking coal accounted for 78 percent of Chinese imports of the fuel in March 2020. By October, that share had dropped to just 26 percent.

The deteriorating relationship between Beijing and Canberra is both the result of the growing great power rivalry between the U.S. and China, as well as bilateral policy conflicts. Australia, with its population of 25 million and its vast continent, is a perfect target for Beijing’s aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy, providing an opportunity to undermine the “Five Eyes” intelligence group (which also includes the U.S., United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand). China worries that the Five Eyes could morph into an unofficial alliance of Western nations and other democracies (like India) aimed at containing it.

Willing to pay the price

Beijing’s attempts to coerce Australia by economic means show its willingness to pay a significant economic price to intimidate other countries that do not respect its interests. As a Chinese government official stated last November: “China is angry. If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy.” At the time, the Chinese embassy in Canberra leaked a document detailing 14 grievances, used as justification for Beijing’s retaliation and intimidation policy. The document denounced Australian government statements critical of Beijing as violations of China’s sovereignty.

China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of steel. Curbing Australian coke imports translated into higher costs for China’s vast steel industry. Coal from Chinese mines is dirtier and costs some 60 percent more than coal from Australia and other foreign exporters. China’s regional competitors in the steel market – Japan, South Korea and India – benefit from the deteriorating Sino-Australian relationship, which allows them to buy Australian exports cheaper.

Facts & figures

The high-quality Australian coal is more efficient than what China produces, and many local power plants depend on it. The reduced supply contributed to widespread electricity blackouts in more than a dozen Chinese cities. Authorities had to dim streetlights, suspend factory production and turn off heating in office buildings.

Potential and dangers

Australia is particularly vulnerable to climate change. Yet it is also one of the best-placed countries to profit from the global transition to renewable energy. The rapid pace of technological development could make Australia a green energy superpower, exporting renewable energy, hydrogen and its derivatives.

Australia’s economic growth was built on maintaining a strategic alliance with the U.S. and developing an ever-closer trade relationship with China. This balance between Washington and Beijing, and between its foreign policy and commercial interests, has become increasingly difficult to maintain. It is a stark example of the challenges many other democracies face due to their growing economic dependence on China and its new confrontational foreign policy.

An Australian expert recently warned: “The message is clear. If your media is overly critical, if your think tanks produce negative reports, if your MPs persist in criticism, if you probe Communist party influence in your community and politics and if you don’t allow Chinese state and private companies into your market, and so on, you will be vulnerable to Beijing’s retribution as well.”