The future of U.S. China policy

The China policy of the coming Biden administration can be inferred from the President-elect’s political trajectory and his election promises. While policy changes are imminent in some areas, others will see a degree of continuation from the Obama era.

In a nutshell

- Joe Biden has nuanced views about Communist Party-ruled China

- There will be some easing in the economic war between the U.S. and China

- On key issues of Asia security, signals from the Biden circle have been unclear

In late November 2020, United States President-elect Joe Biden tapped six individuals to key inner circle positions in his incoming administration. All six are old hands from President Barrack Obama’s term in office (2009-2017); there is an uncanny sense that the Washington establishment is back. This brings both joy and sorrow to China and other Asian countries. But President Biden’s likely policy toward China deserves elaboration.

Forensic prognostication

An assessment can be made by scrutinizing Mr. Biden’s personal political record, his attitude toward and statements on China during his career – especially when he was Mr. Obama’s vice president – and the political trajectories, and views, of his chosen cabinet members. Also, valuable leads can be found in the comments made on China by Mr. Biden and his running mate Kamala Harris during the election campaign. The third source of insight is the Democratic Party – its views of China and, particularly, the Communist Party of China (CPC), can be found in official documents. Finally, there is the president-elect’s and his inner circle’s appraisal of the China policy pursued by the outgoing administration of President Donald Trump.

Two critical questions immediately come up in the analysis. The first is: How do President Biden and his team view China’s rising power?

It is clear that President Trump views CPC-ruled China as a “strategic adversary” all across the board. Mr. Biden, however, seems to have a more nuanced view. While agreeing that China is an ideological adversary, the president-elect defines it as a strategic competitor of the U.S – but on some issues, as a partner. Mr. Biden argues that while the U.S. must compete with China in the fields of economy, technology and defense, it is critical to cooperate with Beijing on climate change, global public health and nuclear proliferation.

The new administration is most likely to seek a limited reset in the hope of creating a more positive and effective China policy.

The second question is: Which power, China or Russia, poses a greater threat to the U.S., especially militarily?

Mr. Biden criticized China sharply. On the campaign trail, he went so far as to call the Chinese leader, President Xi Jinping, a “thug.” And he emphasized in his April Foreign Policy essay that the U.S. must deal with China “forcefully.” Still, these enunciations can also be interpreted as campaign rhetoric. In reality, the new administration is most likely to seek a limited reset in the hope of creating a more positive and effective China policy.

Rival or foe

Both the president-elect and his running mate have described the Russian military as a great threat. Secretary of state nominee Antony Blinken declared at least once (during a TV interview last September) that China poses “the greatest challenge” to the U.S. However, he still holds that Russia represents a very significant threat and the U.S. policy should focus on the regime of President Vladimir Putin.

National security advisor-in-waiting Jake Sullivan, a rising star within the Democratic Party, mostly shares Mr. Biden’s and Ms. Harris’ views on the Middle Kingdom. As recently as 2017, he argued against “containment” as a “self-defeating policy,” advocating instead “a middle course – one that encourages China’s rise in a way that is consistent with an open, fair, rules-based regional order.”

The U.S. policy needs to be about more than just bilateral relations with Beijing – but rather “about our ties to the region that create an environment more conducive to a peaceful and positive-sum China’s rise,” Mr. Sullivan lectured.

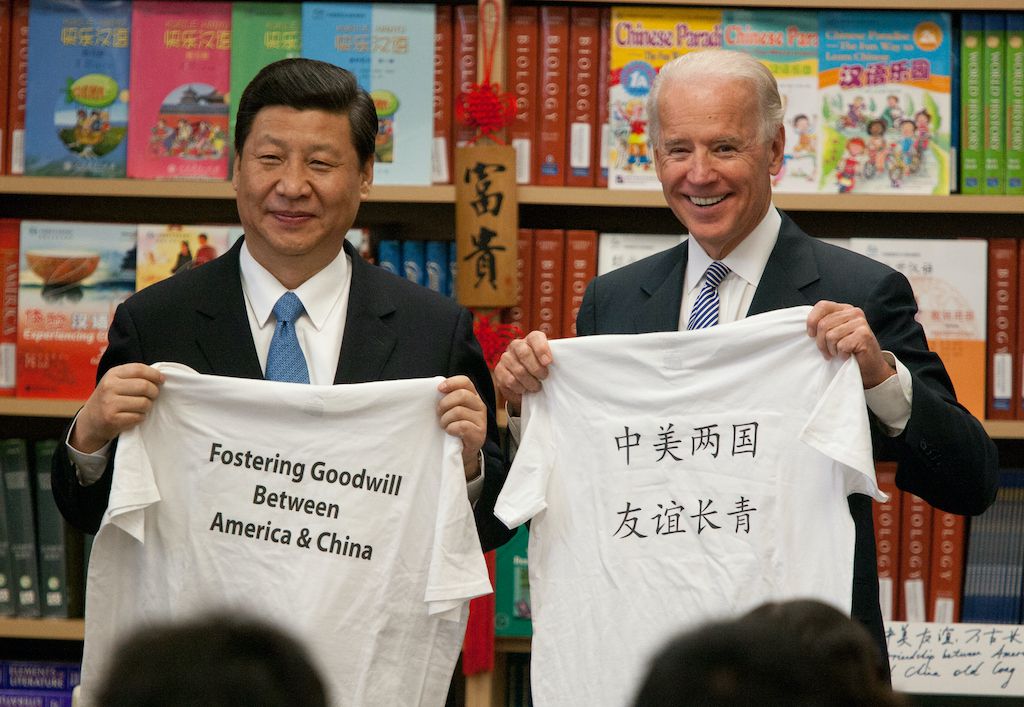

Such theories from top-tier Democrats make it easier to understand why many of Chinese dissidents living abroad heartily supported President Trump’s second-term bid and even condoned his postelection antics and conspiracy theories. Mr. Biden’s record, including his friendly assessment of President Xi during his vice presidency, also contributed to this attitude.

New policy contours

In all fairness, President Biden’s China policy will diverge from President Obama’s lenient approach. Under Mr. Xi, today’s China is very different than it was during the Obama era. The contours of the Biden policy, some of its essential aspects, can already be discerned.

In the economic realm, the Biden administration will likely conduct business in a more transparent, predictable and, arguably, more sophisticated way than its predecessors. “Soft toughness” could be the guiding principle here.

President Biden will have to focus on domestic issues first, due to the Covid-19 pandemic and other immediate challenges the U.S. faces. Adjusting the policy on a range of trade issues, including Mr. Trump’s tariffs, may have to wait. However, it is conceivable that in due time the new administration will try to forge a unified front with U.S. allies on global trade policy to make China abide by international rules. It is likely that Washington will consider joining Asia’s mass-scale trade agreement – the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). But this is technically impossible to take place in the short or even medium term.

Low and high hanging fruit

There is a large question mark, too, over the extent to which Beijing can be made to play by the West’s rules, as Mr. Biden has pledged. For one, President Trump has been unable to push China toward structural economic reform, especially concerning its state-owned enterprises. President Biden stands a no better chance of persuading Mr. Xi and the CPC to get rid of that sector, vital for any state-run economy. On the other hand, there likely will be some easing in the economic war between the U.S. and China. It will benefit the U.S. companies doing business in China and, to a lesser extent, help Chinese exports.

Unlike during the Obama years, Americans will be vigilant when it comes to sensitive know-how.

There is good reason to think that the Biden administration will keep the country in fierce competition with China when it comes to technology. Incoming Secretary of State Blinken made a telling remark recently: that the president-elect had been concerned about China’s use of technology to strengthen its authoritarian grip on the population. One could infer from this that to maintain the U.S. edge over China in high-tech, the new administration will not lift, or significantly ease, the Trump administration’s restrictive measures against Chinese firms.

At the same time, Americans will introduce more proactive measures to promote research and development (R&D). The era of purloining and easy forced transfers of technology from Western firms is over for China. Unlike during the Obama years, Americans will be vigilant when it comes to sensitive know-how.

Volatile security issues

Regarding regional security, signals from the Biden circle have been unclear and even contradictory. If the president were to fall back on the policy instincts and views he expressed as vice president, China could expect to deal with a more flexible, less resolute U.S. than under Mr. Trump. This prospect already worries some Asian countries, especially Japan, South Korea and Vietnam.

On the other hand, Mr. Biden’s consideration of Michele Flournoy, undersecretary at the Pentagon during the Obama administration and veteran of many heated policy debates, for the top defense post raised many eyebrows within the Democratic Party. Last June, Ms. Flournoy published an article in Foreign Affairs, arguing that the U.S. should develop a credible capability to destroy all Chinese naval vessels and submarines in 72 hours to thwart the CCP’s conventional deterrence in the South China Sea. Mr. Biden finally opted for a former U.S. commander in Iraq for the job. However, it is conceivable that his administration will work even harder than the Trump team to ensure free navigation in the China Seas and an effective U.S. presence in the region. This was highlighted in the Democrats’ 2020 party platform.

In the realm of human rights, the Biden administration is sure to be more vocal on issues such as the mistreatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang province, or Beijing’s ruthless drive for total control over Hong Kong. However, given that the Chinese government considers all these issues as domestic affairs and that Hong Kong’s special independent status has already been undermined, it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Biden administration’s criticism could bring tangible results.

Nonetheless, President Trump’s policy restricting international student exchange programs will most likely be revised. The U.S. remains the most desirable country for young Chinese to study. Simultaneously, the Biden administration will likely consider limiting the mainland Chinese’s access to critical technical disciplines.

The biggest unknown: Taiwan

The president-elect’s policy on Taiwan is still vague even though the Democrats’ 2020 platform comes short of endorsing Beijing’s One-China principle and reaffirms its commitment to the Taiwan Relations Act. During the Obama years, the U.S. government pursued a typical “strategic ambiguity” policy in that hotspot. The U.S. is treaty-bound to provide Taiwan with the means to defend itself. It acknowledges Beijing’s stand that Taiwan is part of China but stops short of officially and explicitly recognizing it. Under this policy, Washington assumes that China will want to take Taiwan back by force and the U.S. forces in the region must provide deterrence from that eventuality. On the other hand, the policy encourages cross-strait cooperation and exchange as a means to maintain peace.

President Obama would never have crossed Beijing’s red line in “One China” rhetoric. Mr. Biden also emphasized that no amount of weaponry shipped to Taiwan will guarantee its security and that cross-strait exchanges and communication are essential tools for protecting the status quo.

However, the Trump administration has violated this framework. On November 12, 2020, speaking in an interview on U.S. radio, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that “Taiwan has not been a part of China,” and added: “That was recognized with the work that the Reagan administration did to lay out the policies that the United States has adhered to now for three-and-a-half decades.” Mr. Pompeo’s declaration was followed up by an unannounced late-November visit to Taiwan of a two-star Navy admiral overseeing U.S. military intelligence in the Asia-Pacific region. Such a call would not have been made on President Obama’s watch.

The Taiwanese will be on tenterhooks when the Biden administration starts in January.

Mr. Biden is almost sure to make some conciliatory gestures toward Beijing once he is president. On Taiwan, however, he appears to have no clear new policy. On the one hand, Mr. Blinken, the appointee for secretary of state, has said Mr. Biden would “step up defenses of Taiwan’s democracy by exposing Beijing’s efforts to interfere.”

On the other hand, the Taiwanese authorities vividly remember Hillary Clinton’s attitude toward Taiwan when she was the secretary of state. Wikileaks revealed that in 2011 she received an e-mail from her then-aide Jake Sullivan, who forwarded a New York Times op-ed article by political commentator Paul Kane. Under the headline, “To save our economy, ditch Taiwan,” the author argued that the U.S. could abandon the ally in exchange for Beijing’s cancellation of the $1.14 trillion U.S. debt held by China. In her reply to the aide, Ms. Clinton wrote she found the idea clever.

Regardless of what transpired later, the point is that Mr. Sullivan today is Mr. Biden’s nominee for the national security slot. Faced with China’s relentless pressure on Taiwan, on all fronts, including militarily, Taipei officials will surely miss the Trump era. The Taiwanese will be on tenterhooks when the Biden administration starts in January.

Still, the Taiwanese hope that, aside from their democracy, the island’s cutting-edge semiconductor industry, strongly linked with top technology firms in the U.S., will motivate President Biden to continue offering Taiwan an effective protection.

Scenarios

A limited improvement. Under this script, the U.S.-China relations become steadier after Mr. Biden enters the White House. This will manifest itself gradually in improving trade and cultural exchanges, and also in a better diplomatic climate.

Nevertheless, there will be more question marks over security issues for the Asia-Pacific region than under President Trump, especially during the early part of the Biden administration.

On China’s side, a successful expansion of regional trade and vaccine diplomacy will boost Beijing’s influence and strengthen its Belt and Road strategy in 2021.

Even if the Biden administration continues active U.S. engagement in the Asia-Pacific, tensions in the South China Sea are likely to ease. But in the case of Taiwan, there could be, at best, only a temporary slowdown in President Xi’s drive to take over. No risk-management mechanism will be established in that hotspot. Mr. Biden’s term in office will mark only the preparation phase for the full-blown geopolitical competition between the U.S. and China.

A weakening of the U.S. position. The second, equally possible scenario is more pessimistic. It involves the countries in the Asia-Pacific region being saddled with a Biden administration that falls back on the old habits of framing Asia-Pacific and China policies similarly to those during President Obama’s time in office. Candidate Biden’s many campaign pronunciations give credence to this scenario. There is also fear that the president may have inherited his former boss’s knack for all talk and no action, or much talk and little action.

In the worst-case scenario, American leadership proves no match for the Chinese political elites and the U.S. position in the Asia-Pacific deteriorates significantly. The promises made by Mr. Biden during the election campaign cannot be kept. Taiwan’s government eventually has to find its own way out or surrender.