The decline of social democracy

After a wretched result in last year’s general elections, Germany’s Social Democrats are now voting on whether to enter another grand coalition with the CDU/CSU. Whatever they decide, it may already be too late for the party to pull out of its tailspin. The SPD’s sad decline is part of a much broader eclipse of social democracy in Europe.

In a nutshell

- The decline of Germany’s SPD goes beyond poor leadership and lack of vision

- Populists of the right and left are capturing the left’s anti-establishment base

- Past successes have deprived social democrats of their “unique selling point”

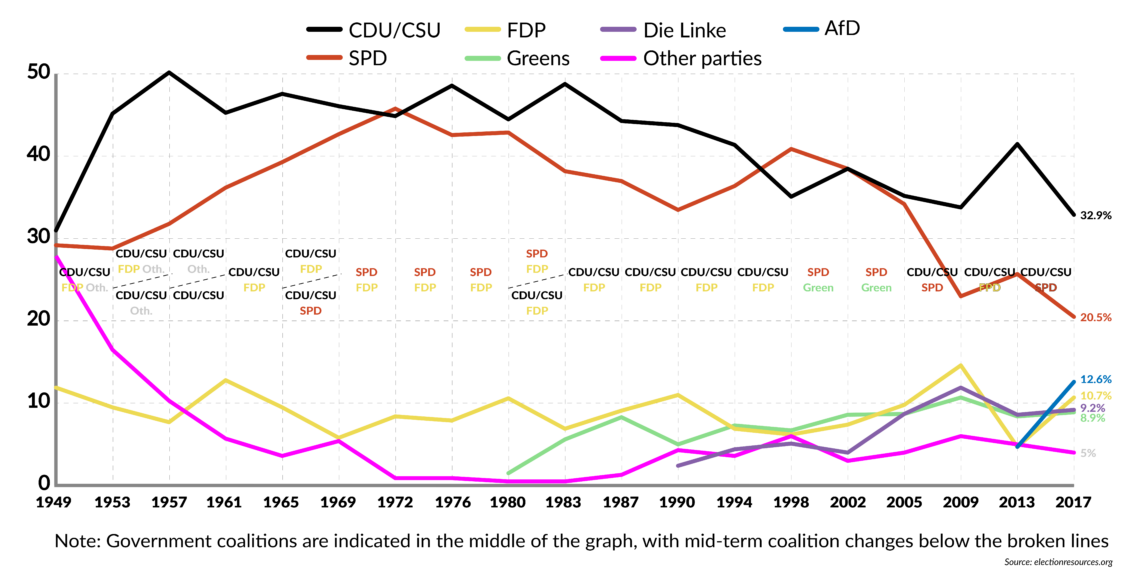

Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) is in deep trouble. Just how much trouble was shown by its 20.5 percent result in the September 2017 election – the party’s worst since World War II.

Already on election night, the SPD admitted defeat and vowed not to reenter a “grand coalition” with the center-right CDU/CSU (whose 32.9 percent result was the second worst in the party’s history). But after Chancellor Angela Merkel’s ruling party failed to coax the Greens and Liberals into a new coalition, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier (a two-time foreign minister for the SPD) publicly appealed to his party to act responsibly. After painful soul-searching and with the narrow approval of party delegates, the Social Democrats once again entered coalition talks with the Christian Democrats – more than four months after the elections were over.

Whether Germany’s two establishment parties – dubbed “the coalition of losers” – will form a government remains to be seen. The preliminary coalition agreement has to be approved in a referendum of the SPD’s 463,000 members, and the party’s unpopular leader (Martin Schulz, who finally resigned on February 13) has been having a hard time selling it to the base. Meanwhile, opinion surveys have the SPD polling in the mid-to-high teens, with a sensational Feb. 16-19 INSA poll showing the party falling behind the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) into third place.

The SPD is bereft of a grand vision and lacks credibility as a defender of the poor, huddled masses.

What happened to the proud party that once dominated German politics with chancellors like Willy Brandt (1969-1974), Helmut Schmidt (1974-1982) and Gerhard Schroeder (1998-2005)? There is no shortage of explanations. In the past two general elections, the party leaders who ran against Angela Merkel – Mr. Schulz and Peer Steinbrueck – had the charisma of a local bank teller. The SPD also lacks credibility as a defender of the “poor, huddled masses” after Mr. Schroeder’s effective but unpopular labor market reforms in the early 2000s. Even more obvious, the Social Democrats are bereft of a grand vision for Germany’s and Europe’s future – something the left has always needed more than the pragmatic center-right.

But the reasons for Social Democracy’s decline go deeper. And they are not restricted to Germany.

Populist squeeze

Among the 28 member states of the European Union, only six have governments led by social democrats (Italy, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Sweden). In last year’s elections, socialists or social democrats were virtually wiped out in France (5.7 percent), the Netherlands (5.7 percent) and the Czech Republic (7.3 percent); in Austria, they lost to a center-right coalition. Social democratic parties have no parliamentary representation at all in Hungary and Poland, and have been relegated to a marginal role in Greece (6.3 percent). Among larger EU states, only the Labour Party in the United Kingdom registered a surprising increase in votes during last year’s snap election.

That exception may be telling, too. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is a graybeard and Marxist dinosaur who spent decades on the fringes of British politics. Now he embodies the antiestablishment populism of the far left. In Germany, Mr. Corbyn’s positions would be regarded as far outside the social democratic mainstream and much closer to Die Linke, an outright socialist party.

Populists of the right and left tend to overlap on substance, including hostility toward open markets and transatlanticism.

Europe’s rising radical populists of the right and left tend to overlap on substance, including such hot-button issues as hostility toward trade and open markets, or opposition to transatlanticism in foreign policy and defense.

What these parties or “movements” mostly share is (a) disdain for elites and experts of all kinds; (b) claims to represent the “true” will of the people, homogeneous and united in their goals; and (c) a presumption that complex problems will always yield to straightforward, simple solutions.

The SPD’s biggest losses in the September 2017 election (some 500,000 votes) were to the AfD on the populist right. Together with their leftist counterpart Die Linke, these two parties can now claim to represent those “left behind” – especially low-income voters in underdeveloped rural areas and eastern Germany. Combined, they have a larger constituency than the SPD.

This has far-reaching implications. With the advent of the AfD, the prospects for a German leftist government under Social Democratic leadership have vanished. Back in 2013, the left spectrum (the SPD, Greens and Die Linke) could still claim a majority in the Bundestag. The only reason a grand coalition was formed was because Die Linke was deemed unfit to govern. Today, these leftist parties claim less than 40 percent of the vote.

The new mainstream

It has often been argued, especially in SPD circles, that the main reason for the party’s decline was its relegation to a junior partnership in the grand coalition with the CDU/CSU. However, this is hard to prove with bare facts. In 2013, the SPD barely improved its vote (and was far outdistanced by the ruling CDU/CSU) despite having spent four years in the opposition. And in 2017, the party lost its traditional stronghold of North Rhine-Westphalia, even though it had ruled there at the head of a center-left state government.

Facts & figures

SPD on the skids

German federal election results by party, 1949-2017

Nevertheless, the argument that the SPD has lost its edge – or in business terms, its “unique selling point” – seems justified. Like many other European parties of the center-left, its appeal to the underprivileged parts of society has been overshadowed by populists of the left and right.

One reason for this is that social democrats, when in government, must often abandon traditional goals like guaranteeing jobs in industries that have become uncompetitive, or redistributing income and wealth even if it means increasing taxes and debt. As Margaret Thatcher famously said: “The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money.” This is particularly true if other people and businesses can take their money and investments elsewhere in the age of digitalized globalization.

That is what happened in Germany 15 years ago, when the country was regarded as “the sick man of Europe.” Gerhard Schroeder, its Social Democratic chancellor, reacted by overhauling Germany’s rigid labor laws and bloated welfare system. This caused massive estrangement among the leftist clientele of the SPD, which has not won a national election since Mr. Schroeder’s second term in 2002. His reforms backfired badly on the party, but paid off handsomely for the country. Germany regained its competitive edge, allowing it to take the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession in stride. Somehow, the SPD leadership failed to take credit for this accomplishment, and voters continue to ascribe economic competence and success to the center-right.

Europe lives in an age of social democracy, yet social democratic parties are in retreat.

A second reason why the SPD has lost its appeal is that social democracy has become the new mainstream ideology, espoused on many occasions by the center-right. Whenever typical social democratic demands (such as a higher minimum wage, enhanced welfare and retirement benefits, or same-sex marriage) gained popularity, the CDU/CSU under Angela Merkel swiftly endorsed them – stealing credit from the SPD for being socially progressive. This technique of Ms. Merkel’s – called “asymmetric demobilization” – may have driven some conservative voters to the AfD, but it has damaged the SPD far more seriously.

The end, my friend

More than ever, perhaps, Europe is living in an age of social democracy, yet social democratic parties are in retreat – defeated by their own success. There were failures as well. Many socialist and social democratic parties were too complacent about their traditional constituencies among public-sector employees and industrial labor unions. They were correspondingly slow to react to the new challenges of digitalization, globalization and migration.

To escape this trap and revive social democracy as a political force, two strategies are available.

One follows the road of the populist and radical left. The surprising success of three old Marxists – Bernie Sanders in the United States, Jean-Luc Melenchon in France and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK – in whipping up enthusiasm among idealistic young voters could present a tempting example. However, it is worth noting that while all three men “rocked the establishment,” none managed to win an election. Even if they did, socialist idealism would run into the hard constraints of reality, and great expectations would turn into great disappointment.

The alternative is to emulate Emmanuel Macron: free oneself of old socialist party structures and mentality, then create a centrist and mildly antiestablishment grassroots “movement.” Grandiose visions of Europe’s future could be combined with pragmatic reform measures, which might even yield results before the next elections. In any case, vigorous activity creates the impression of charismatic young leadership.

Either one of these paths would be the end of social democracy as we have known it.