A paragon of democracy suffers a hiccup

For months now, Chile has been rattled by political protests. President Sebastian Pinera has tried to assuage tensions by investing in social programs, but the measures have proven insufficient in the eyes of the population, who continues to demand a new constitution.

In a nutshell

- Chile is facing demonstrations over the political status quo

- The Pinera government will hold a constitutional referendum

- Uncertainty over the outcome is straining the economy

Since mid-October, Chile has been roiled by protests that have paralyzed its economy and upended its politics. The result has been a moment of upheaval and collective soul-searching, unlike anything Chile has seen since its return to democracy over 25 years ago. How the country emerges from its current turmoil and semi-paralysis will have important implications for the future of market democracies across Latin America.

Unrest on Chile’s streets is nothing new. Mass demonstrations focused on the cost of higher education crippled Santiago in 2006 and 2011. And in 2016, frustrations with the nation’s social security system boiled over into a week of marches and strikes. But this most recent social movement is distinct in both its size and its nebulous ambitions. The only unifying platform that has been articulated thus far is a deep discontent with the current state of affairs.

‘18-O’

The slogan adopted by the protesters – “Chile desperto,” meaning “Chile has awoken” – captures the sense of widespread frustration without identifying what is wrong. Most commentators simply refer to “18-O,” the date, October 18, when the protests began. Many protesters believe the source of the problem is the market-oriented consensus that has defined Chile since the days of the Pinochet military dictatorship (1973-1990). For them, the market is running roughshod over social issues.

Other equally fervent protesters would say that the root of the problem is not the free market model itself, but the abuses and privileges generated by an unfair system. Much attention has been focused on how Chilean politics and business are dominated by graduates of a handful of Santiago high schools, and how wealth has been concentrated into the hands of an economic elite who monopolize markets and hold enormous sway over the political system. Pinochet’s dictatorship is viewed by these protesters as the turning point when such inequalities were created. Replacing the Pinochet-era constitution, which has been in effect since 1980, is seen as the only comprehensive solution.

The protests brought a level of violence that has not been seen since the 1970s.

The Chilean protests evoke striking parallels to protests that crippled Brazil in 2013, which, as in Chile, began in response to a small increase in public transportation prices. Also, as in Chile, the protests emerged “out of nowhere.” The sitting president of Brazil at that time, Dilma Rousseff, had an approval rating of above 60 percent. But the protests, though initially small, snowballed into riots that manifested broad discontent from across Brazilian society. Ms. Rousseff’s efforts at a rapid policy response were insufficient. Eventually, that movement was hijacked by a political class who used it to force President Rousseff from power in a legally dubious impeachment proceeding. This example has undoubtedly been on the mind of Chile’s President Sebastian Pinera, who has vowed that he will not resign from office before his term expires in 2022.

The protests had brought a level of destruction to Chile that has not been seen since the early 1970s when the country nearly descended into civil war. Arson and vandalism have caused more than one billion dollars in damage – even the Santiago metro system, once the crown jewel of Latin American public transit, was crippled. Meanwhile, thousands of people – both protesters and police – have been injured in clashes, including several hundred blinded from rubber bullets.

Two dozen demonstrators have been killed. Multiple accusations of human rights violations led the UN to send investigators, who produced a damning report documenting extensive improprieties by the police. And yet, despite prominent images of violence and vandalism, the vast majority of the protests have consisted of peaceful marches and cacerolazos — a tradition of banging empty pots and pans to evince frustration. Mr. Pinera’s initial response focused only on the fraction of demonstrations that had turned violent. “We are at war with a powerful enemy,” he declared in a hastily arranged news conference in October. “They are relentless and do not respect anyone or anything.”

Too little too late

Former Minister of the Interior Andres Chadwick (now facing criminal charges for human rights violations), threatened to prosecute protesters under an anti-terrorism law used to suppress the indigenous Mapuche people during the Pinochet era. This style of stern saber-rattling has always played well with President Pinera’s base, a group of Chilean voters who live in perpetual fear of a descent into Venezuelan-style chaos. But it proved a completely tone-deaf response to the mass outpouring of peaceful marches and community gatherings.

President Pinera, urged on by Mr. Chadwick, declared a state of emergency under another law that had gone unused since the Pinochet era. Ten thousand soldiers enforced a curfew in Santiago that lasted over a week. Images of the military violently arresting protesters en masse rekindled memories of the dictatorship. Eventually, President Pinera realized the extent of his mistake and accepted the resignations of half of his cabinet, including the interior minister. For most Chileans, that and subsequent gestures were too little, too late.

Since Mr. Chadwick’s firing, President Pinera has adopted a more moderate tone – though that has not been enough to revive his approval ratings, which stand at 6 percent. He is, fundamentally, a pragmatist determined to see out his term. The president also understands that if there is any hope of preserving the core of the Chilean free-market economic model – one that is nearly unique in South America – he must disassociate laissez-faire economics from authoritarian governments.

Facts & figures

Chile has long been the poster child for a development model centered on open markets and fiscal restraint as well as a firm commitment to the rule of law, coupled with social programs similar to more developed countries in the OECD. And, by almost all measures of economic well-being, Chile’s record since returning to democracy in 1990 has been one worthy of envy. In the past 25 years, income per capita has quadrupled to nearly $25,000 per year, the highest in Latin America and more than double the average for the region. Poverty rates, meanwhile, have plummeted: In 1989, nearly 40 percent of the population lived on less than $5.50 per day; today, that number is only 7 percent.

Inequality has been frequently cited as a catalyst for the protests and it is true that Chile remains extraordinarily unequal. However, as measured by the Gini coefficient, inequality has been falling since the 1980s. It has more or less flatlined over the past half-decade, holding steady around 0.5. The fact that inequality has stopped dropping even as Chile’s economy has continued to grow is one telling indicator when it comes to explaining the protests. Perhaps a more important driver behind the protests is the concentration of wealth, which is increasing among the privileged economic elite, because it is directly tied to governance.

New constitution

A more powerful driver of discontent, however, seems to be the remnants of the Pinochet military rule that continue to structure Chilean society, most notably the constitution crafted under the dictator. Many of the focal points of frustration: the higher education system, the social security system, the privatization of public goods like water, are laid out in the constitution. And while the document has been amended numerous times, including significant reforms in the 2000s, protesters have called insistently for its wholesale replacement.

The nature of the Pinochet constitution helps to explain the nature of some of the complaints. When former President Michelle Bachelet (2014-2018) tried to put together a supermajority called the New Majority (Nueva Mayoria) to rewrite the constitution, she failed and her coalition fragmented. As a result, there is little leadership from Chile’s political opposition in helping the protesters formulate an agenda for debate.

It seems almost certain that voters will overwhelmingly opt for a new constitution.

In a surprising move that acknowledged the depth and force of the protests, Mr. Pinera took the first step to accede to the demand for a constitution change by agreeing to a plebiscite, eventually scheduled for April 2020. It will give voters the chance to vote, first on whether they want to replace the existing constitution, and, second, on the rules that would govern the election of participants in the constitutional convention, if such were to take place.

While much could change by April, it seems almost certain that voters will overwhelmingly opt for a new fundamental law. It might have been considered a minor blessing that nearly two-thirds of the Chilean urban populations took some time off during the southern summer, but they returned ready to take to the streets again. The massive demonstrations for International Women’s Day only added to the energy of the protests.

Scenarios

If Chileans do vote for a new constitution on April 26, as seems likely according to opinion polls, the country will enter a period of tremendous institutional uncertainty. The April plebiscite, in the case of a “yes” vote, would be followed with elections held in October to determine the members of the constitutional convention. Fundamental questions about how these members would be selected remain unanswered. Would there be quotas for women and for indigenous groups, for example, to ensure their representation? Would the constitutional convention members be drawn from the legislature or the nation at large? Would citizens need to affiliate with a political party to nominate themselves for the convention?

These crucial questions and the uncertainty they represent are dwarfed by the unpredictability that would be involved in drafting a new constitution. The convention, if it goes forward, will have carte blanche to write a new document from scratch. Property rights, social rights, the makeup of a supreme court, the independence of the central bank, the structure of Chilean elections, and the constitutionally-mandated “subsidiary” role of the state in healthcare, pensions, and education – all of these and more would be up for revision.

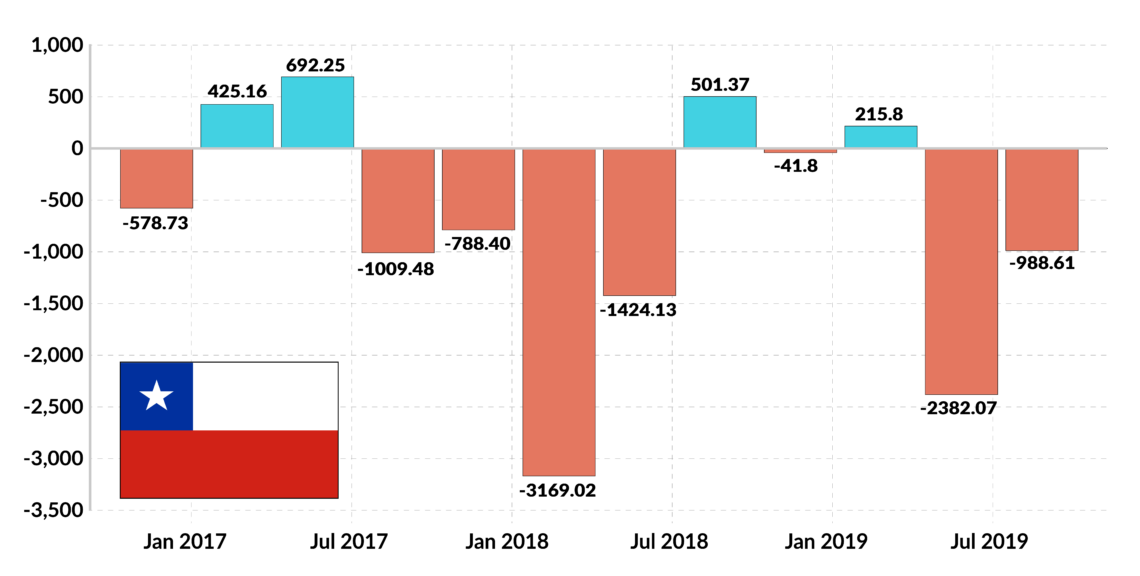

It would be a fool’s errand to predict how the country’s basic law would change if a convention were called. What is clear is that confusion surrounding the constitutional outcome will generate financial distress, especially in the realm of foreign investment. On the day when President Pinera announced the constitutional referendum, the peso plummeted nearly 13 percent. While it has now recovered from those historic lows in December, it remains dramatically weaker despite substantial propping by Chile’s central bank. If a constitutional convention occurs, the volatility of the peso and of Chile’s markets are almost certain to remain, fluctuating in tandem with the apparent likelihood of changes in Chile’s property laws or market regulations.

Continued volatility and a dampening of foreign investment would hit the state mining concern, Corporacion Nacional del Cobre (Codelco). The company has been struggling to raise the capital needed to upgrade its mining operations and remain competitive on a global scale. The state had once planned to inject $20 billion into Codelco over the next decade. However, new Finance Minister Ignacio Briones wants those funds redirected to programs intended to quell social unrest.

That leaves the concern, already saddled with nearly $20 billion of debt, to seek capital on the open market. There could hardly be a worse moment for that, as uncertainty and pessimism in the international financial market over the coronavirus spread and the dramatic slowdown in the Chinese economy makes access to capital problematic. At the same time, in a vicious feedback loop, if Codelco is unable to upgrade its mines, tax revenues generated from copper production and royalties, a vital source of income to the Chilean state, will decline.

Though Codelco’s issues are particularly acute, they are also emblematic of the challenges that the broader Chilean economy will face in the months ahead. Already, GDP is estimated to have decreased 1-2 percent as a result of the social unrest, severely limiting the funding available for precisely the types of social programs with which President Pinera hopes to assuage the protesters.

While unlikely, another scenario could play out in the run-up to the April plebiscite. The president’s abysmal approval ratings could encourage his own coalition to seek his resignation. That would be an unprecedented and extremely disruptive move in Chile’s strong presidential system and President Pinera has repeatedly declared his intention to see out his term. Nonetheless, if protesters return to the streets in the numbers seen in December, even the president’s most fervent supporters would be forced to confront the fact that he has become toxic in the eyes of the vast majority of the nation.

In an uprising that is amorphous and ill-defined, one source of discontent has been abundantly clear: the status quo must not be maintained and no one personifies the status quo quite like Mr. Pinera.