China’s soft landing in the Balkans

In the next few years China will be opening an investment bridgehead in the Balkans. As other powers such as Russia and Turkey have increased their geopolitical presence in the region, China’s expansion will be even stronger – but different in kind because it will be a “soft,” mostly economic penetration.

In the next few years China will be opening an investment bridgehead in the Balkans. Other traditional powers have increased their geopolitical presence in the region, notably Russia and Turkey. China’s expansion will be even stronger, yet different in kind because it will be a “soft,” mostly economic penetration. This push will be all the more powerful if the European Union decides to neglect the region, as seems probable with its decision to delay the next round of accession until 2025. Keeping the Western Balkans out of the EU will provide fertile ground for Chinese ventures such as the “16+1 Initiative” – part of the much larger Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Thus, the next decade promises to open a new sort of geopolitical fault line in the Balkans, alongside traditional interethnic disputes and the larger rivalry between Russia and the West. This time the battlefield will be economic, and the fight will be over Chinese investment capital. Russia and Turkey will keep trying to draw the region into their orbit, meeting opposition from the United States and the EU. That leaves room for China to make inroads in its own quiet fashion.

In the time when the “new Cold War” between Russia and the West is reaching an alarming pitch, China is not militarily engaged to either bloc and can turn the confrontation to its own advantage. Beijing’s first step will be to become a key economic player in the Balkans; political leverage will come later. By keeping an equal diplomatic distance from Washington and Moscow, and capitalizing on a strategic partnership with the EU, China will use the Balkans as an easily accessible “no man’s land” to make a European entrance. The main conduit will be Mediterranean ports.

With only 20 million inhabitants, the Western Balkans do not represent an important market for Chinese products. The region is more useful for its location. Compared with Russia’s energy and arms sales and Turkey’s commercial interests, China is much more concerned with the Western Balkans as a transit route to the EU’s huge internal market.

In its search for new markets, China has made improved logistics an overriding goal.

China, which may account for 20 percent of global GDP by 2030, is making economic expansion a priority. Trade and investment diplomacy has become the key to its foreign policy. In its search for new markets, China has made improved logistics – faster and cheaper connections – an overriding goal. This strategy was only reinforced by the Communist Party’s 19th Congress in October 2017.

The mammoth BRI program – with its overland and maritime components (the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road) – gave a new direction to Chinese foreign policy. Oriented toward the West and intended to give China the leading role in Eurasia, the project was launched in 2013 as Beijing’s top geopolitical priority.

By interlacing Central and South Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe with dense transportation and communications networks, including a new Eurasian Land Bridge, it aims to create a shared space accounting for 70 percent of the world’s population, 55 percent of its economic output, and 75 percent of its energy reserves. Ultimately, the goal is not only to create a better external environment for China’s economic growth, but also to give Beijing more say in world politics.

Destination Europe

With such global ambitions, China is more interested in building a financial network in Southeast Europe than in constructing military blocs around the Baltic and the Black Sea, as NATO and Russia are doing. Since Beijing prefers not to give up any negotiating leverage (which it would need to do if it dealt with the EU as a whole), it employs a “state-by-state” strategy for developing individual projects with European countries, including those in the Balkans.

Nevertheless, there is no doubting the importance of the EU in Chinese strategy. In trade terms, China accounted for more than one-fifth (20.2 percent) of the bloc’s imports and 9.7 percent of its exports in 2016, according to Eurostat. The annual 180 billion-euro trade deficit with China has caused strains, prompting the EU to adopt anti-dumping and other protectionist measures. Investment inflows mirror trade, as Chinese foreign direct investment into the EU totaled 35 billion euros in 2016, a 77 percent increase from the year before, while EU outward investment into China fell by a quarter.

Beijing is trying to encourage trade liberalization and free access to the single market by supporting the euro area, including holding approximately one-fifth of its monetary reserves in euros. In addition to intensive economic relations, Chinese officials held 88 high-level meetings with EU representatives in 2013-2016.

From the European point of view, China is one of its main strategic partners and a force to be reckoned with, along with the United States and Russia. The EU is beefing up its diplomatic presence in China while developing bilateral policy channels like the Connectivity Platform (2015) to coordinate projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative. At the same time, the European Commission has prepared a plan for screening Chinese infrastructure investments. “If a foreign state-owned company wants to purchase a European harbor, part of energy infrastructure or a defense technology firm, this should only happen with transparency, scrutiny and debate,” Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said while announcing the plan in September 2017.

In fact, only 15 EU member states have agencies to screen foreign investments, which will make it no easy task to implement Mr. Juncker’s plan. Most exposed will be countries like Greece and Hungary, whose fragile economies are heavily dependent on foreign investment. Greece was the site of China’s first major infrastructure project in Europe, by the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), which in 2009 acquired a 35-year concession from the Greek government to upgrade and operate two container terminals at the port of Piraeus.

Investment race

The Western Balkans is the perfect springboard for China’s expansion strategy. The region borders directly with the EU and its countries enjoy zero customs regimes with the bloc.

Some of China’s headline infrastructure projects in the region are with Serbia. This includes a 350-kilometer high-speed railway line between Budapest and Belgrade that will ultimately link up with Piraeus; a $260 million bridge across the Danube in Belgrade; and a new 350 MW coal-fired power unit in Kostolac, Serbia’s first new electric capacity to be installed in 30 years, financed by a 700 million-euro Chinese loan. A much larger long-term project is the proposed Danube-Morava-Vardar waterway to the Greek port of Thessaloniki, which would ultimately provide an inland link for bulk cargoes between Dutch ports and the Aegean Sea. Hungary, Serbia and Macedonia would be directly involved in this mammoth project, whose total cost is estimated at 15 billion euros.

Macedonia is a good example of how China uses its diplomatic leverage at the UN.

Politically, China has supported Serbia’s insistence on not recognizing Kosovo, giving Belgrade a second “no” vote among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. This will delay indefinitely Kosovo’s membership in the United Nations, until an agreement can be worked out with Serbia. Beijing was also reluctant to allow Kosovo to attend Interpol’s annual meeting in Beijing, leading Pristina to delay its application to that organization for another year.

A good illustration of how China uses diplomatic leverage at the UN is its treatment of Macedonia in the early 1990s. At that time, the new government in Skopje decided to recognize Taiwan. Beijing immediately froze bilateral relations and vetoed continuation of the UN Preventive Deployment Force (UNPREDEP) mission to Macedonia. China only relented after Macedonia withdrew its recognition for Taiwan. But while diplomatic relations have normalized, Chinese engagement in Macedonia remained minimal for many years, even after the Macedonian authorities tried to entice investors with a free economic zone.

Recently, China loaned Macedonia 580 million euros for two highway projects: Skopje-Stip and Kicevo-Ohrid. Beijing has earmarked another 500 million euros to the Republic of Macedonia for projects related to the new Silk Road initiative. Skopje hosted a high-level regional meeting of Chinese and Balkan officials in October 2017, and Macedonian President Gjorge Ivanov declared for the first time that his country needed China as much as the EU. His somewhat desperate tone is understandable given Macedonia’s protracted economic crisis, which caused it to be dropped from the World Economic Forum’s “Doing Business” list of 137 countries in 2017.

Brotherly love

With Albania, China’s special relationship goes back to the 1970s. After withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact in 1968, Albania was ignored by NATO and found itself suspended between two hostile military blocs. The country’s communist leader Enver Hoxha turned to a “fraternal alliance” with Maoist China, based on common ideological ground. Albania thus has the oldest sustained friendship with China of any country in the Balkans.

Postcommunist Albania has recently increased its economic cooperation with China. A visit by Prime Minister Edi Rama to Beijing in 2014 was soon followed by the announcement of a new railway project in EU Pan-European Corridor VIII, which would run from Durres – on Albania’s Adriatic Coast – to the Bulgarian Black Sea port of Varna. A Chinese company is also expected to win a concession to build the Ionian-Adriatic highway, which will run from Albania through Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia to Italy.

A key factor in improving Chinese-Albanian economic ties is Beijing’s goal to establish a strong presence in European ports. Albania is well-positioned in this regard, with three major harbors on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas: Durres, Vlore and Shengjin. After Piraeus in Greece, these Albanian ports could be an important bridgehead for China’s commercial entry into Europe.

Albania’s government has offered China a 25-year concession on Shengjin’s port in return for modernizing its infrastructure. China will gain access to an Adriatic port within easy reach of Italy; while Albania – in addition to a major boost to its economy – may be able to soften the Chinese attitude toward Kosovo and its majority Albanian population.

There is no doubt that the Western Balkan countries will be competing against each other for Chinese investment, which can make a huge difference in an economically depressed region. (A Serbian business association calculated that the average annual salary in the region is lower than in 21 African states.) The main competitors will be Albania and Serbia – an interesting pairing of opposites. Albania has the longest friendly relationship with China, while Serbia’s economic ties were closer during the postcommunist period. Albania is the western terminus of Pan-European Corridor VIII, while Serbia is astride north-south Corridor X. Albania is a member of NATO, while Serbia is Russia’s historical partner in the Balkans.

The ‘16+1’ process

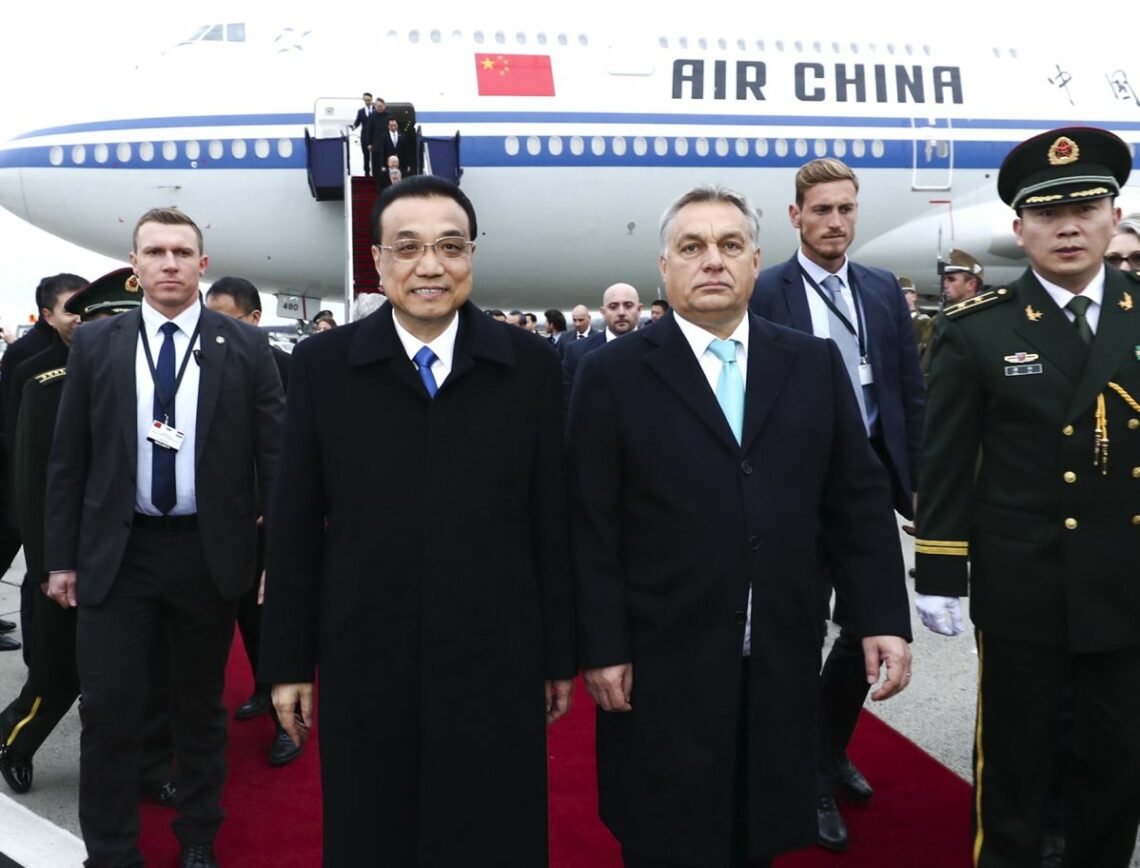

Apart from individual relations with each Balkans state, Beijing has also pursued a regional process known as the “16+1” initiative. Started in Warsaw in 2012, it has continued with subsequent meetings in Bucharest, Belgrade, Riga and Bratislava. The most recent 16+1 summit, on November 27-28, 2017, launched several investment projects. Foremost among these is a “Transport Community” to link up Pan-European Corridors VIII and X, with Macedonia occupying the main crossroads position.

The Chinese government has earmarked 10 billion euros to finance infrastructure projects in these 16 Central and Eastern European countries. Top priority will go to road, rail and water transport over the two pan-European corridors, which add up to a kind of mega-terminus in Southeast Europe for the Maritime Silk Road. These investments also reflect a wider competition between China’s vast Eurasian project and the EU’s own “Berlin Process” designed to prepare the Western Balkans for accession.

China wants to penetrate the world’s richest internal market by acquiring bridgeheads on the EU’s periphery.

China is attempting to realize its strategic goal of establishing a presence inside the EU – the world’s richest internal market – by acquiring bridgeheads in non-member states on its Balkan periphery. Ports and land corridors are equally important. The region is also a crossroads of energy corridors, such as Russia’s “Turkish Stream” pipeline and the EU’s Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which carry additional geopolitical implications.

Scenarios

What do Beijing’s activities to date tell us about its plans in the Balkans? The answer is contained in two possible scenarios.

The first – and somewhat less likely – possibility is that China will stick to its state-by-state approach to economic cooperation. This emphasis on bilateral ties would naturally tend to accentuate the Albanian-Serb rivalry for regional dominance as they strive to attract as much economic and political support from China as possible. Economic competition would take place along the alternative transport routes (Corridors VIII and X), while the venue for diplomatic rivalry would be the United Nations, especially concerning recognition for Kosovo.

Under this scenario, China would benefit from its nonaligned status in the “new Cold War” between Russia and the West, acting as an arbiter or even tipping the scales. Most of all, China will be guided by its own interests. That suggests it will refrain from using its veto against Kosovo (which would be taking sides against the U.S.) and at least abstain (so as not to spoil relations with Russia). Beijing will probably try to repeat this global balancing act in the region as well, by seeking to equilibrate between Albania and Serbia.

The second scenario would see China taking a more comprehensive approach, using the “16+1” process as a template for wider regional initiatives. The drawback here is the exclusion of Kosovo, which is required by China’s policy of nonrecognition.

This leaves a major hole in the “16+1” program and the regional transport network. If China proposes to make Albania’s Shengjin its second port in Europe, then it cannot ignore the overland route through Kosovo. Serbia itself is dependent on the port of Durres and is already building its portion of the Nis-Pristina-Durres motorway.

Failing to support transportation projects in Kosovo would also not sit well with the EU and the U.S. – international partners that China cannot afford to ignore. This suggests that Beijing will come under increasing pressure to write Kosovo into its regional infrastructure plans, in analogous fashion to its inclusion in the EU Berlin Process (even though five EU member states do not recognize Kosovo).