Colombia seeks radical change by electing Gustavo Petro as president

Mr. Petro’s victory extends the Latin American trend of rejecting incumbent parties. The president wants to raise taxes, boost social spending and curb fossil fuels.

In a nutshell

- The president was a senator, a former M-19 guerrilla and ex-mayor of Bogota

- Even before taking office on August 7, Mr. Petro softened his leftist agenda

- A legislative majority may help his chances of delivering radical changes

The leftist Gustavo Petro won Colombia’s June 19 presidential election, triumphing with 50.4 percent of the runoff vote over the populist outsider Rodolfo Hernandez. His victory marks a repudiation of politics as usual and is a milestone for Colombia, which has never been governed by a socialist. He took office in the Latin American nation of 51 million people on August 7.

Mr. Petro, a former M-19 guerrilla and mayor of Bogota, long led presidential polling by a wide margin and had earned more than 40 percent of the May 29 first-round vote. His support was buoyed by voter dissatisfaction with the right-of-center government of Ivan Duque and support from the poor.

Still, his victory was by no means assured. Mr. Hernandez, a businessman and antiestablishment outsider who had been compared to Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, was a slight favorite in the week leading up to the election. He capitalized on the electorate’s fatigue with standard-bearer politicians of all ideological stripes and managed to surpass right-wing Federico Gutierrez, known simply as Fico, in a first-round upset. Mr. Hernandez, however, faltered in the weeks before the runoff vote, refusing to appear in a televised debate with Mr. Petro.

President Petro and his Historic Pact coalition appear to have won by using his political machine to turn out voters. He received nearly 2.7 million more votes in the second round than the first, and the overall turnout was the highest it has been since 1994. The presence of Afro-Colombian Francia Marquez on Mr. Petro’s ticket likely helped drive support for him in the western departments of Cauca, Narino and Choco, where he earned more than 80 percent of the vote.

Rejection of the status quo

Mr. Petro’s election marks the 12th straight free and fair presidential election in Latin America in which the incumbent party has lost power. There has not been such a strong regional mandate for change since the transitions to democracy began in the 1980s.

The contest itself represented a blow to Colombia’s traditional parties and the country’s professional politicians. In the first round, Colombian voters abandoned the center and moved away from the traditional right, turning what had promised to be a showdown between the establishment right and the antiestablishment left into a contest between two options representing a break from politics as usual. Massive social protests in 2019, 2020 and 2021 had foreshadowed voter sentiment, but many parties and candidates failed to heed the warnings.

The results lay bare the vacuum in Colombia’s political center. Sergio Fajardo, the former mayor of Medellin and the Center Hope coalition candidate, placed a distant fourth in the first round, with a meager 4 percent of the vote – far worse than in 2018, when he earned 23.8 percent of the vote and fell only 1.5 percentage points short of making the runoff. Although his coalition performed well in the March legislative elections, his individual performance reflected a chaotic campaign marked by the resignation of Ingrid Betancourt, who dropped out of the presidential race and threw her support to Mr. Hernandez.

Gustavo Petro supports taking steps to bolster the fragile 2016 peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla group.

The same is true with the failure of the traditional right and its candidate. Right-wing candidate Mr. Gutierrez arrived with the backing of the Conservative Party, the Liberal Party, the Party of the U, the Radical Change party, and the Christian MIRA party, as well as tacit support from the governing Democratic Center led by former President Alvaro Uribe Velez. This coalition would have guaranteed him a majority in congress, but the trappings of establishment support worked against him in the campaign – especially his association with the unpopular President Duque and the toxic Mr. Uribe. As with Mr. Fajardo, Mr. Gutierrez’s failure shows how deep voter dissatisfaction runs with standard-bearers. Instead, voters opted for two antiestablishment candidates to shake up the status quo.

Policy proposals

On the campaign trail, Mr. Petro promised to enact sweeping change to Colombia’s economic and social structures. Along with being the former mayor of Bogota, he was a senator. He also finished second to President Duque in the 2018 presidential contest. This time around, he campaigned on a platform to increase social spending and reduce the country’s inequality. His policy proposals included scrapping private pensions, taxing unused agricultural land, and raising the corporate tax burden. He pledged to use the new tax revenue to fund universal free higher education and a minimum wage for single mothers while cutting the government deficit.

In addition to these core economic issues, Mr. Petro supports taking steps to bolster the fragile 2016 peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla group and is a vocal proponent of peace talks with the National Liberation Army (ELN), the last active guerilla group. The president has also spoken in favor of legalizing drugs, which would mark a radical shift from the country’s current approach to narcotics. In foreign policy, Mr. Petro’s team has already announced it will pursue the normalization of relations with Venezuela.

These proposals, along with promises to end new oil exploration and ban fracking, have alarmed Colombia’s business community and many in the middle class. In fact, Reuters news agency reported claims that some oil and real estate companies signed agreements with a so-called “Petro escape clause,” invalidating contracts if he were to win. The president-elect understands these concerns. In April, he was moved to issue a statement in the presence of a notary in which he pledged not to carry out expropriations if elected.

Challenges

Mr. Petro will face several challenges, from a polarized electorate to a difficult financial situation to the inequality and insecurity that hampered President Duque’s administration. Governing will not be easy, as he is pulled between demands to deliver on his promise for radical change and the reality of governing with the compromises required to keep the support of a coalition majority in the legislature.

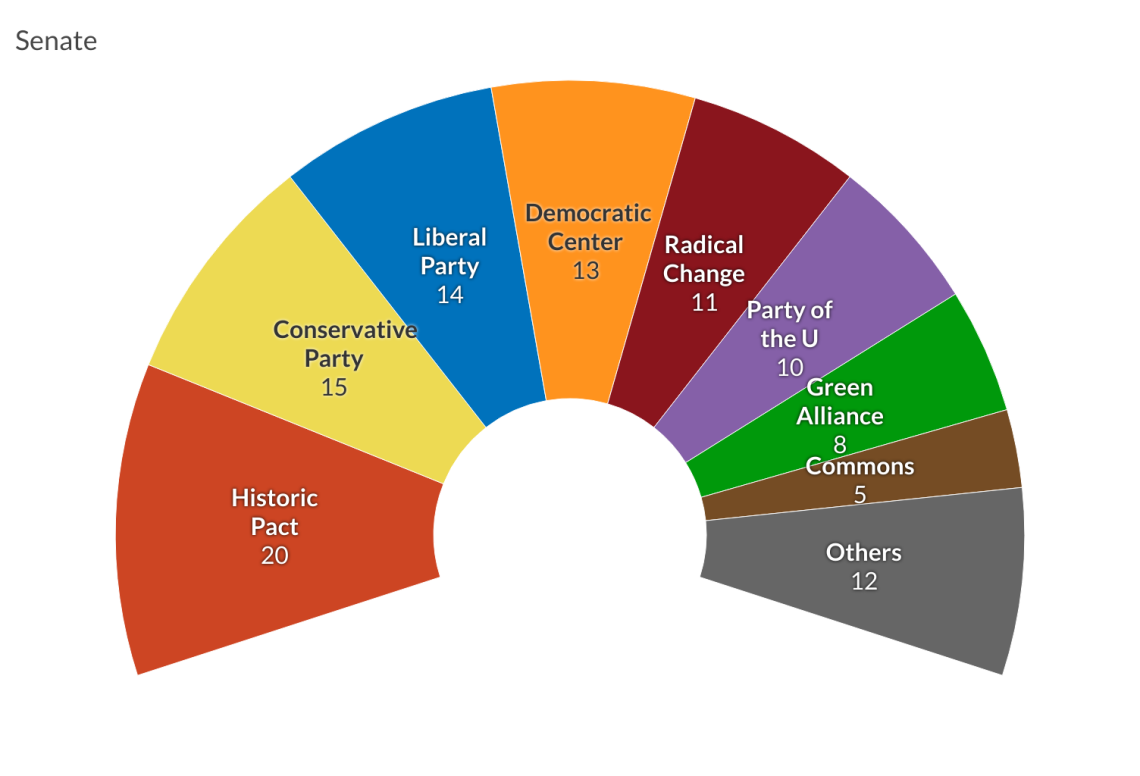

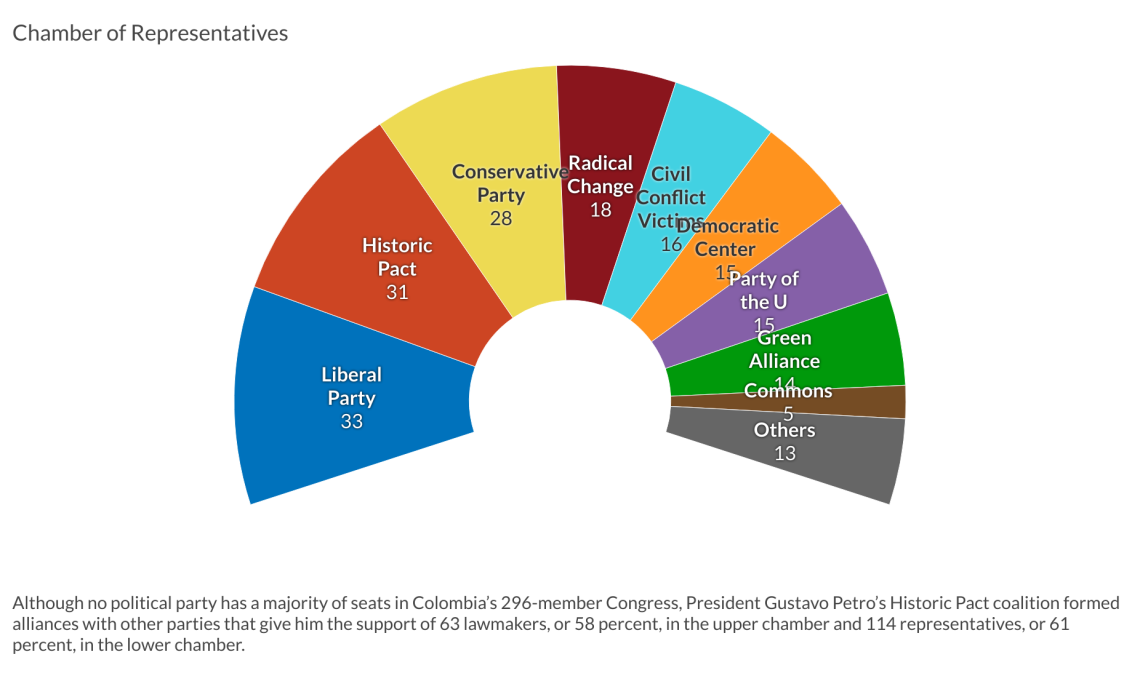

By July 20, he had secured a working legislative majority in both the upper and lower chambers. The president’s Historic Pact alliance will have the support of 63 out of 108 lawmakers in the Upper House and 114 out of 186 representatives in the Lower House until the next election in 2026. The majority was bolstered when the U Party’s 10 members said they would join the presidential coalition.

On August 1, Mr. Petro’s transition team prioritized environmental policies, the implementation of the 2016 peace accords with the FARC, negotiations with the ELN, and a moratorium on new mining contracts for the administration.

The most immediate concern is the economy. Annual inflation is expected to hit a 22-year high of 9 percent in 2022. The higher food and fuel prices have alarmed an already restive population. Moreover, Mr. Petro has made progressive tax reform a centerpiece policy. This is difficult enough to achieve under normal conditions, let alone amid low growth and high inflation.

The country’s security situation also presents a problem, as Colombia still has at least 20,000 enemy combatants.

The fiscal deficit is likely to grow. The new administration plans to cut mining and oil projects that will harm the country’s balance sheet while the cost of the proposed social programs will eat through government money. Something will have to give, and before his term is up, Mr. Petro will have to make some tough decisions on revenue and spending.

The country’s security situation also presents a problem, as Colombia still has at least 20,000 enemy combatants, including the ELN, dissident FARC groups, paramilitary groups, and especially the Clan del Golfo drug trafficking organization, which has already approached Petro with an offer to disband in return for generous amnesties. Key aspects of the government’s peace accord with FARC, particularly those related to rural economic development and reintegration, remain unrealized.

Unfortunately, as in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and other countries throughout the region, President Petro will find governance difficult.

Due in part to Colombia’s unusual counter-honeymoon electoral cycle – legislative elections shortly before the presidential ones – no party has anywhere close to a majority in Congress. And despite the presidential results, centrist and traditional parties continue to be the most important at the congressional level. Mr. Petro’s Historic Pact earned the most seats in the Senate but came in second in the Chamber of Representatives behind the Liberal Party. Colombia’s Congress has 296 members and, with coalition partners, the president has a majority in both chambers. However, traditional parties and politicians, especially those in the center, are quite likely to play an outsized role in the coalition.

Scenarios

Broad coalition and a balancing act

Given these constraints, the most likely route in the short term is that Mr. Petro forges agreements and alliances with traditional parties to get things done. In doing so, the president will have to moderate his proposals, grant concessions to more centrist actors, and show a willingness to distribute cabinet portfolios to other parties.

There is already some evidence of an attempt to moderate leftism. In selecting his cabinet, Mr. Petro has announced the appointments of two traditional politicians, Jose Antonio Ocampo and Alvaro Leyva as ministers of finance and foreign relations, respectively.

Mr. Ocampo is a progressive liberal whose proposed policies echo President Gabriel Boric’s reform agenda in Chile, with higher social spending financed through greater taxation on the wealthy. However, Mr. Ocampo, who previously served as finance minister and co-director of Colombia’s Central Bank, is one of the country’s most well-known economists and his appointment provides reassurance to markets and other sectors about the administration’s radicalism. Likewise, the appointment of Mr. Leyva as foreign minister suggests a measured approach to the country’s security situation. He is an economist and conservative lawyer. A longtime politician, the incoming minister promoted the peace agreement in Havana between the government of Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC guerrillas.

Mr. Petro will need to be strategic in further appointments if he is to build cross-party support for his policies.

Legislative gridlock

Despite the imperative to build alliances, however, the president may find it difficult to maintain support for a full four years. To begin, he will face pressure from historically marginalized groups as well as his vice president, who has not been keen on the prospect of granting concessions to traditional parties, to realize his grand campaign promises and promote radical social change. Attempts at meeting these demands will likely alienate potential allies in Congress and lead to a legislative stalemate. In this same way, the deterioration of the country’s fiscal situation is likely to require unpopular policy changes.

It is also notable that Mr. Petro’s experience in Colombia’s Senate is that of an adversary, who has been quick to fight with opponents and allies alike. No matter the size or composition of his coalition, this does not bode well for passing legislation and implementing policy in the long term.

A move to the left and executive rule

If congressional negotiations fail, some worry that Mr. Petro may pursue his policy goals via executive fiat, or worse, govern in the mold of authoritarian leftists like Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, or Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel. Seizing more executive powers is certainly possible: in the campaign, Mr. Petro suggested that he could declare a state of emergency, which would allow him to issue a flurry of executive decrees. His postelection actions to build a broad coalition, however, suggest that this is the least likely short-term outcome.

The possibility that he will turn into a dictator seems even more remote right now. Mr. Petro’s track record as a politician and the conditions under which he took power are much different than those surrounding the other leaders, and Colombia’s new president will not enjoy the support of the military or other entrenched power structures. In either case, governing via decree would exacerbate polarization, invite judicial challenges, and undoubtedly imperil his administration.

Ultimately, the composition and durability of Mr. Petro’s governing coalition will determine how much success he enjoys with his policy goals. Failure to improve the country’s economic or security situation is likely to spark further protests and erode the new president’s political capital. It may also send voters to pursue different promises of change.