Germany’s ‘fat years’ are over

Over the past decade, Germany has worked hard to keep its public finances sound. The coronavirus crisis will undoubtedly change that state of affairs. The question now is whether Germany will keep its fiscal discipline once Covid-19 subsides.

In a nutshell

- For a decade, Germany has kept its debt in check

- High taxes have allowed it to run budget surpluses

- Lower taxes may now be the stimulus the economy needs

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

Of all the geopolitical and economic powers in the G20, Germany is the only one to have registered a budget surplus over the last several years. Since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2007, government debt among G20 nations has increased by 72 percent, while gross domestic product (GDP) has only grown 31 percent. The G20’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 63 percent to 81 percent between 2007 and 2018.

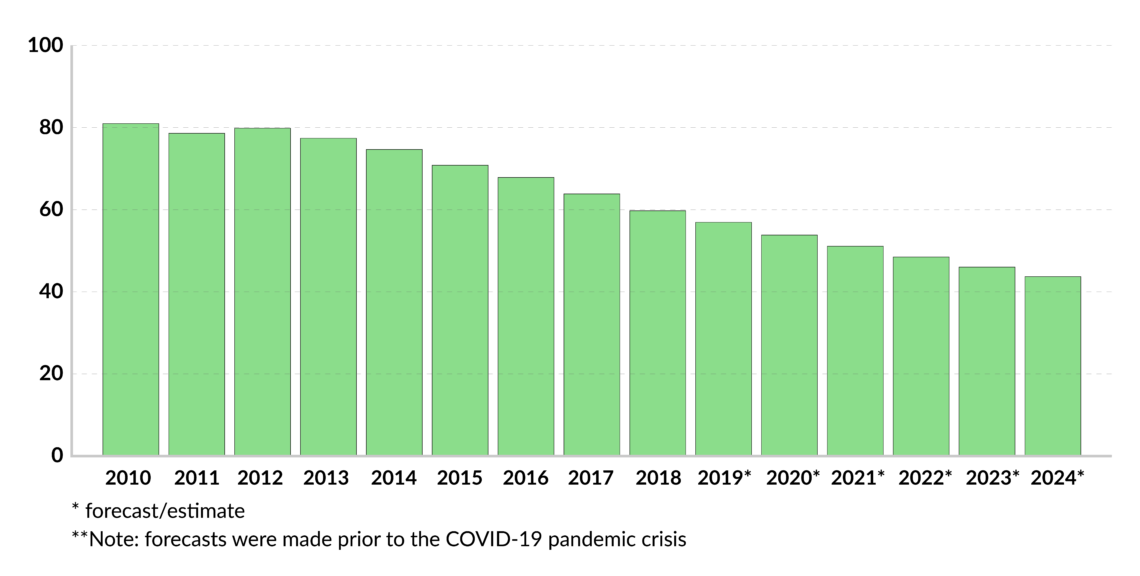

Germany first followed the trend, then reversed course. Since 2010, it has slashed its public debt-to-GDP ratio from 81 percent to below 60 percent, meeting the eurozone criterion of sound public debt for the first time in 18 years. As shown in the graph above, the International Monetary Fund estimated that this trend would continue for the next several years.

That was before the coronavirus crisis occurred. The IMF made three key underlying assumptions. First, it expected GDP growth to continue at a modest but positive average rate of about 1.3 percent. Second, record low (even negative) interest rates would further reduce the costs of servicing public debt. Third, public expenditures would be kept in check by the new constitutional “debt brake” rule.

No one expects German government bond rates to rise anytime soon.

Of these three assumptions, only the low interest rate forecast remains viable. No one expects German government bond rates to rise anytime soon – they are more likely to remain in negative territory. That would not have changed if Germany had entered a mild recession, as GIS wrote in a 2019 report, published before the coronavirus crisis hit.

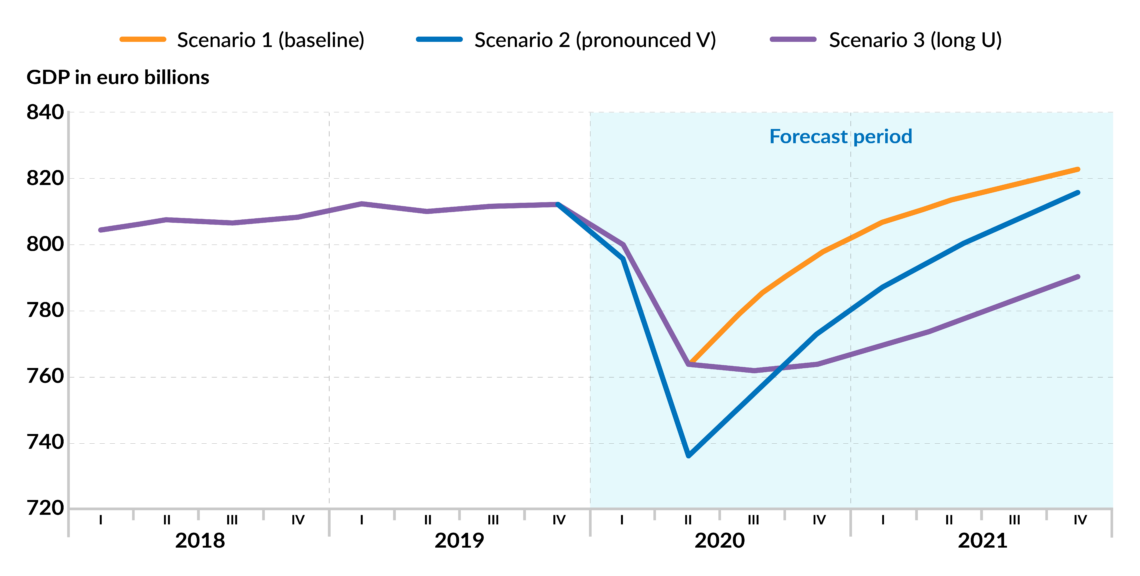

At the time of this writing, the impact of the pandemic and the mitigation measures on GDP remains very uncertain. The German Council of Economic Experts recently published scenarios that see a range of GDP losses for 2020 of between 2.8 and 5.4 percent and a potential rebound in 2021 of between 1.0 and 4.9 percent growth. Other studies are gloomier and predict that with a shutdown duration of two months, the costs in Germany could reach 255-495 billion euros and reduce annual GDP growth by 7.2-14.0 percentage points. With longer shutdown periods, the costs go up to 354-729 billion euros and 10-20.6 percentage points of lost growth.

As a consequence, the IMF’s third assumption (continued balanced budgets) will also become void. In a swift reaction to the crisis, the German treasury has put in place “an assistance package of historic proportions,” as the government puts it.

The federal government will take out additional loans totaling roughly 156 billion euros to support employees, self-employed people and businesses. The states are implementing similar supplementary budgets. Much more money is promised in terms of equity measures and loan guarantees for German businesses. The total of directly budget-relevant extra expenditures is more than 350 billion euros (almost the size of the total federal budget in 2019); the amount of new guarantees amounts to a staggering 820 billion euros.

Breathing room

Still, the fiscally conservative German public and most German economists deem this unprecedented public spending spree – even compared to the extraordinary measures taken following the financial crisis when German GDP fell by 5.6 percent in 2009 – acceptable and necessary. It is hoped that the recession will be more short-lived, giving way to a V-shaped recovery as economic activity regains a semblance of normalcy. And more than in 2009, Germany is supposed to be able to afford more public spending.

Facts & figures

Longtime GIS readers already know the details of the decisions made in 2009. Back then, the CDU/CSU-SPD grand coalition amended the German constitution to introduce the “debt brake” (Schuldenbremse) – a balanced-budget provision that took full effect a few years later. From 2016, the federal government has been forbidden from running a structural deficit of more than 0.35 percent of GDP. Germany’s states (Länder) would not have been allowed – under normal circumstances – to run any structural deficit starting in 2020.

It is important to note that the debt brake rule does not mean the government can never run a deficit. The legislation restricts itself to the “structural deficit.” This accounts for business cycle fluctuations and allows “automatic stabilizers” to do their work: during a recession, government tax receipts fall and expenditures rise. This temporary deficit does not count as part of a structural deficit. Also, the rules permit exceptions to be made for emergencies such as a natural disaster or severe economic crisis.

Today, Germany is reaping the benefits of this strategy to forestall future debt crises and create confidence in sustainable public finances. Thanks to the debt brake (as well as low interest rates and export-fueled tax revenues), the German government was able to build up the fiscal breathing space that comes in so handy now.

Time for a tax ‘brake’?

Governments can generate economic stimulus through increased government spending or tax cuts. Prima facie, both tend to grow public debt. Yet both can also support private consumption, employment and investment in times of crisis, or stimulate them afterward, helping public finances recover.

Germans shoulder one of the world’s highest burdens of taxes, fees and social insurance payments.

Even some proponents of watering down the debt brake are skeptical of increasing government spending at the expense of private investment. Room for fiscal maneuver can also be used to lower taxes, they argue. They have a point: Germans shoulder one of the world’s highest burdens of taxes, fees and social insurance payments.

Germany’s recent budget consolidation did not result from reckless austerity – government spending has increased in almost all areas except for servicing debt. Instead, it stemmed from stubbornly high taxation in an environment of high employment and positive growth. In the 2013 to 2021 period (which has included two election cycles), tax receipts have increased by 380 billion euros.

Hence, one way to keep German firms (especially the small ones) in business at times of steep demand decline and supply-chain disruption is to relieve taxpayers. Lower corporate and income taxes could increase competitiveness, boost returns and spur private investment by German businesses. It would also help the aging German population (a significant concern for the long-term sustainability of German fiscal policy, see below) better secure its future.

Scenarios

Even without the coronavirus crisis, the era of budget surpluses in Germany would most likely have ended this year. In the short term, the enormous spending on recovery initiatives, along with the recession-related drop in tax revenue, implies that the German debt-to-GDP ratio could quickly jump from slightly below 60 percent to somewhere around 70 percent in just one year.

Besides, Germany is entering election mode. There is even the lingering possibility of early elections before the official date in autumn 2021. As in other countries, when elections loom, parties tend to outdo each other with proposals on how to spend more. The spending priorities include digitization, as Germany’s broadband and mobile phone infrastructure are less advanced than in many other OECD countries. Also on the list are renewable energy and electric mobility, affordable housing, education, road and rail infrastructure, and, of course, even more social benefits.

At the moment, all this is considered of minor importance compared to tackling the virus and its immediate economic impact. But once most of the population develops antibodies to the virus, many Germans may again fall into the old habit of asking other people to pay for the things they want.

[[quote]]Assuming the pandemic will not have dramatic, drawn-out implications for the global economy, Germany’s long-term future faces two countervailing forces: aging and the stability of the debt brake.

A major source of stress on Germany’s fiscal stability is its aging society. Most of the country’s baby boomers will retire during the 2020s. At the same time, a relatively small number of young people will enter professional life – and pay taxes. The demographic transition will have substantial consequences for budget viability. This March, the finance ministry published its public finance sustainability report. The key variable is how much money the government will have to come up with to meet all obligations arising from demographic change.

The report develops two scenarios to 2060. In its optimistic scenario, governments at the federal, state and municipal levels, as well as social insurance organizations, would lack an extra 50 billion euros, or 1.5 percent of GDP. Under the pessimistic scenario (lower growth, less employment participation), the gap would be 140 billion euros – or 4.1 percent of GDP. As early as 2025, the country would see increasing structural deficits, leading to a debt-to-GDP ratio in 2060 of 75 percent in the optimistic scenario or 180 percent in the pessimistic one.

That is a very wide range of outcomes. However, as long as the German debt brake remains a binding commitment, German governments will have to make tough decisions on priorities.

My baseline scenario is that academic doubts and political temptation will not suffice to formally dismantle the constitutional balanced-budget rule formally. Doing so requires a two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament and would be unpopular. Hence, there is only a 10 to 20 percent probability that official public structural debt will sharply increase in the next five to 10 years.

It is much more likely that officials will find creative ways to circumvent the debt brake’s strict rules. In addition to creating “shadow budgets” (financial commitments that are not appropriately accounted for), politicians can declare “unusual emergencies beyond the control of the state” to adhere to the rules while still running big deficits.

A simple majority in the Bundestag can declare such emergencies. The coronavirus was an obvious and justified example. However, in the (unlikely) case that the German Constitutional Court accepts climate change as an emergency and allows the government to take parts of the excessively costly German energy policy out of the structural deficit calculation, much higher deficits would suddenly be legal.

Germany’s “fat years” of budget surpluses are over. But for the longer term, I still expect the debt brake (along with very low interest rates) to have at least a dampening effect on excess deficits in Germany.