How China missed a chance to stop Covid

The head of the WHO praised China’s response in Wuhan as swift and transparent, but there are reasons to challenge this view. Authorities suppressed early reports of the disease’s danger, delaying action when the spread of the virus could be best contained.

In a nutshell

- China failed to act early on to contain coronavirus in Wuhan

- Responsibility for the failure falls squarely on the government

- Local medical professionals in China reacted properly

After China moved to shut down the city of Wuhan to try to prevent the spread of coronavirus, its President Xi Jinping was lavishly praised by Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, head of the World Health Organization (WHO). The transparency and swiftness with which Chinese officials had sprung into action impressed the official. “The speed with which China detected the outbreak, isolated the virus, sequenced the genome and shared it with the WHO and the world are very impressive, and beyond words,” he said, and noted that China was setting “a new standard” for outbreak response.

People in China, however, have been questioning the authorities’ handling of the crisis, especially in its initial phase – the best time to stop a potential epidemic in its tracks.

Disturbing facts

Looking closely at the events in December 2019 and January 2020, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the disaster has been, to no small extent, human-made. Here is, in chronological order, what happened in the period shortly before the shutdown of Wuhan:

- Early December: The appearance of a new kind of flu is reported by Dr. Zhang Jixian, a Wuhan-based respiratory expert. Two weeks later, she warns that human-to-human transmission of the virus is taking place

- December 27-30: Reports about the new virus appear on the internet and are promptly censored by the authorities

- December 31: Under public pressure, the municipal government reports 27 cases of infection, seven of them severe. The first expert group is sent to Wuhan by China’s Ministry of Health

- January 3: Coronavirus begins to spread to other Chinese cities, such as Shenzhen, Weizhou and Changsha, though the number of infections is initially small

- January 4-8: Hong Kong, as well as Thailand, Japan and other countries, report individual coronavirus cases spreading from Wuhan

- January 7: The virus has infected seven medical workers treating a patient in China. This development is not officially reported

- January 16: The Wuhan Health Commission insists that there is no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission related to coronavirus

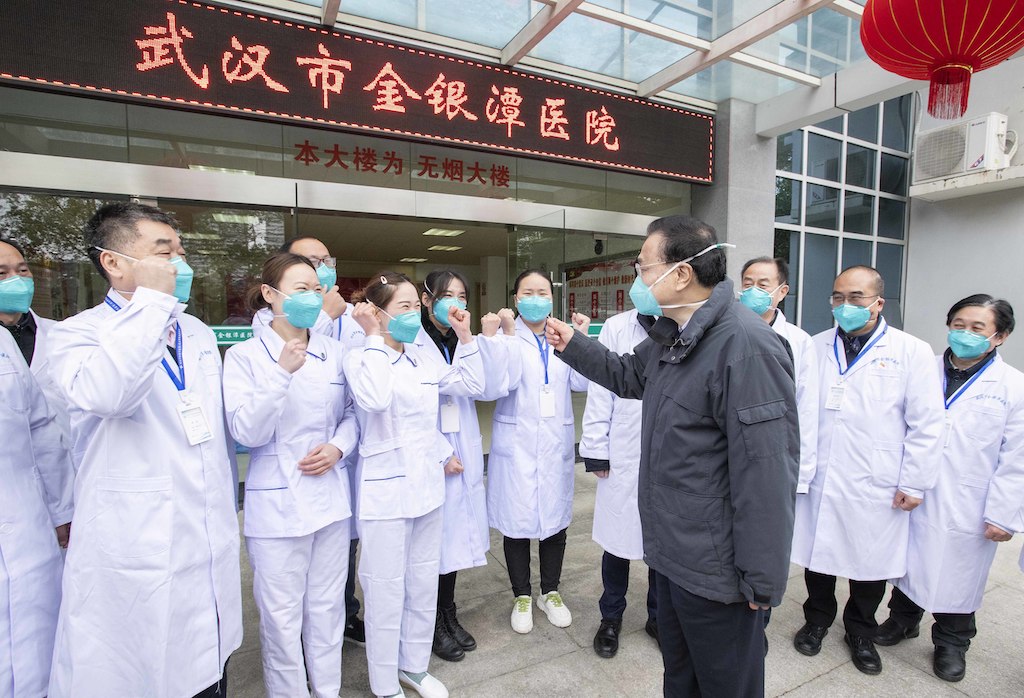

- January 20: A second expert group headed by Zhong Nanshan (the epidemiologist and pulmonologist who discovered the SARS coronavirus in 2003) goes to Wuhan and delivers its conclusion: human-to-human transmission is evident. The Communist Party of China orders radical measures to combat the disease. The Epidemic Prevention and Control Command in Wuhan is established

- January 23: Wuhan becomes a closed city

If January 20, 2020, can be regarded as the watershed moment in the struggle against the coronavirus, the days from January 7 to January 19 must be seen as being of utmost importance for that effort. During that period, the authorities failed to disclose that the deadly disease can be transmitted between people. No effective measures were taken during the 13 days to avoid a nationwide and possible worldwide epidemic.

By the end of December 2019, some medical workers had already realized that the virus could be transmitted from human to human. On December 30, eight individuals, among them Dr. Li Wenliang, sent messages to three newsgroups via the popular Chinese social media application WeChat, warning their colleagues and friends of a newly discovered SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)-like virus.

Silencing doctors

Dr. Li himself identified the rapid spread of infection among the family of a coronavirus patient being treated in the hospital. However, his and some others’ voices were quickly muted by China’s “stability maintenance” apparatus. Worse, these people were all held by the police for allegedly spreading rumors. The detentions ended with official warnings. To intimidate others who might follow in the footsteps of these “rumor mongers,” their apprehension was reported by TV stations and other media in the country.

For nearly three weeks, until January 20, the local government tried to hide the scale of the outbreak.

The authorities made a concerted effort to conceal information about how the virus could be transmitted at a time when they already had highly credible information about it. The official rhetoric had it that the unknown virus was “controllable” and “preventable.” This intended playdown of the danger led to the fabrication of false information, distortion of reality and, above all, complacency among local government officials.

When coronavirus emerged in December, municipal virologists in Wuhan promptly reported it to the authorities. One of the key institutions in charge of such matters is the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. According to an insider source, the nature of the coronavirus pneumonia was identified at the beginning of January 2020. By January 11 (at the latest), government officials in decision-making positions should have been informed about the danger – that is, that the virus could be transmitted between humans, was deadly and could be highly contagious. Unfortunately, there was no sufficient reaction in the upper levels of the state.

Facts & figures

The Wuhan Health Commission did announce the appearance of the novel coronavirus on December 30, 2019, but for nearly three weeks, until January 20, the local government tried to hide the scale of the outbreak. The motivation was political: China’s ruling establishment is concerned above all about social stability and the image of the Communist Party.

From January 11 to January 17, the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (NPC & CPPCC) of the province held their annual meeting in Wuhan, a prominent political event in the area. Only good news is welcome under such circumstances. It was thus no coincidence that the Wuhan Health Commission, a government organ, refused to publish any report about the spread of the virus in that period. It so happened that on January 11-12, eight more medical workers (not to mention several other citizens) were infected with the coronavirus. The infection of medical workers (altogether 15 by January 12) was made public only on January 21.

Worse still, despite their knowledge of the contagious nature of the virus, the municipal and provincial government officials did not cancel a “10,000-family banquet” extravaganza on January 19, and a New Year Show on January 21 in Wuhan. Neither had they prevented the outflow of 5 million people in the critical time (January 10-20) to other places. Beyond doubt, these events facilitated the spread of the coronavirus.

Belated apologies

Only recently, Wuhan’s Communist Party chief admitted during a televised interview that the impact of the epidemic could have been reduced had the necessary steps been taken in a timely fashion. It is rare for a party leader with the rank of secretary (though not at the highest level), to publicly admit mistakes. But his reflection arrived late.

Prominent experts who served as key advisors for the decision makers also have not lived up to their responsibilities.

The Wuhan mayor sought to shift the blame by pointing out that as a local government official, he had no mandate to disclose volatile information. His statement could be construed as a reproach of President Xi Jinping’s one-person-rule leadership style. On the other hand, the mayor was trying to pass the buck to his superiors (although it is likely that he had not received any instructions from the central government before the January 20 signal for action).

Not only politicians failed to act responsibly. The technocrats and prominent experts who served as key advisors for the decision makers have not lived up to their responsibilities either. After the coronavirus was initially detected, on December 30, the State Council sent a group of experts headed by Dr. George F. Gao, director general of the Chinese National Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to investigate. On January 27, The New England Journal of Medicine, one of the world’s leading medical journals, published a paper on China’s coronavirus. Dr. Gao is one of 40 Chinese authors. The paper provided detailed data based on 425 early cases, gathered during the authors’ stay in Wuhan. Mr. Gao and his colleagues produced a robust analysis, concluding that initial cases of the novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia occurred in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 and January 2020.

The authors of the paper understood the danger of the virus. Nevertheless, they kept it to themselves during the critical days before January 20 as they waited for the paper to be published. As a result, the CDC failed to respond promptly to the outbreak of the disease. Valuable time was lost.

Blame-shifting games

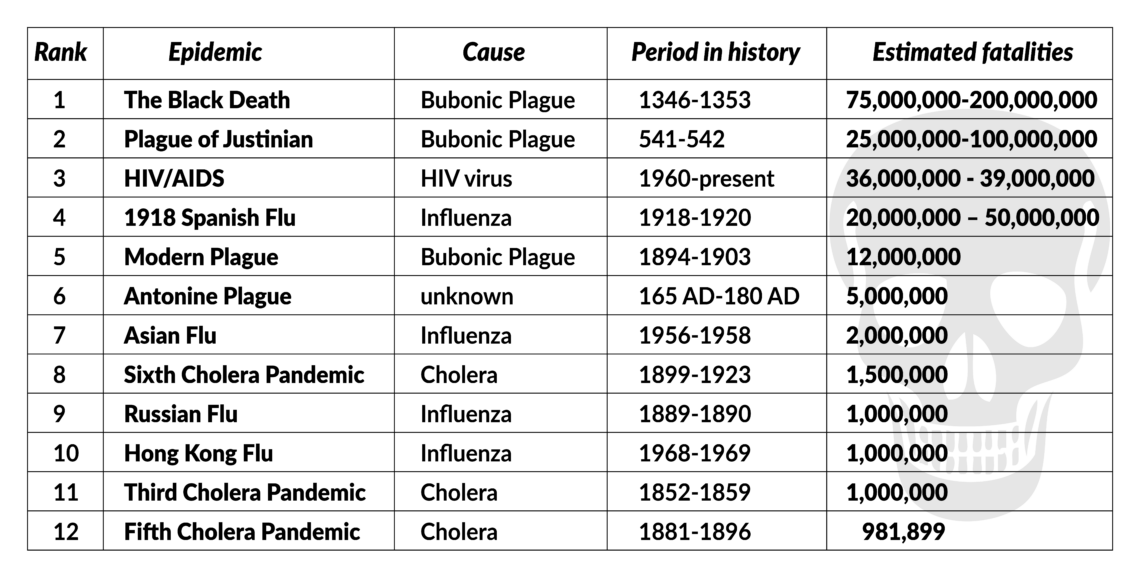

The death toll of the coronavirus has already surpassed that of SARS. The Communist Party, the health authorities and the local government in Wuhan are engaged now in blame-shifting games. By official rules of the Chinese state, enshrined in public heath laws, however, the health officials, national and local, only have the competence to report problems to the other parts of the government. Once informed, all the local governments have an unshirkable responsibility to disclose information to the public and promptly undertake necessary measures to protect its safety.

The reality in China looks different. It is characterized by two contradictions rooted in its political system and recently deepened by President Xi’s quest to centralize power. One is the contradiction between the role of the Communist Party and the government’s competence. Mr. Xi has reversed the trend, going back to the 1980s, of gradually confining the power of the Party. Now its “leading role” is emphasized. During his recent meeting with the head of the WHO in Beijing, Mr. Xi is said to have told Dr. Ghebreyesus that he personally was in charge of the virus-containment effort. That assertion was later omitted in the official communique from the meeting – apparently because of the steadily worsening epidemic.

Hushing up the reality and understating the danger in such a precarious situation can be explained in only one way.

The second contradiction lies between rule of law and rule of the Communist Party. As mentioned before, local governments have a legal mandate to handle public health emergencies. Yet their hands are tied because, in the end, the party has the final word. Although China’s laws are mostly harmonized with the prerogatives of the party, there are exceptions. The rules for dealing with an epidemic are one such case.

Scenarios

It is true that, to an extent, Beijing has learned the lesson from SARS. In 2002 and 2003, the country was criticized for concealing information that was essential for the world to know. It is impressive that the Chinese CDC sequenced the coronavirus’s genome within seven days of its appearance and informed the WHO and the international community. At the same time, information about the virus was released with a significant delay domestically.

Beijing always handles what it considers inside information with the utmost care and tries to make sure that the outside world never gets a full picture of developments taking place in the country. The same strategy was employed on the coronavirus story.

Comparing China’s effort to eradicate the SARS epidemic in 2002-2003 with today’s activities, it is clear that things have changed dramatically regarding technical means and medical technology. China’s economy is significantly larger, so its resilience is likely to be better if the crisis deepens. However, in terms of information policy and the general transparency of the government’s actions (determined by the country’s institutional arrangement), things have remained mostly unchanged.

Hushing up the reality and understating the danger in such a precarious situation can be explained in only one way: officials see it as a defense of the Communist Party’s interests. That was precisely what happened before January 20, 2020. In this context, the WHO head’s outburst of enthusiasm over China’s response to the epidemic may have pleased Beijing, but it only undermines the credibility of an important organization with vast global responsibilities.

Today, the Communist Party of China is fully mobilized to contain the coronavirus epidemic. President Xi has made it the government’s highest priority to stabilize the economy and shield society. But the cost of the delay is already becoming evident. The president exudes confidence that he and his party cadre can overcome all the difficulties. Success, however, will hinge on many other factors, too – among them the fast and accurate flow of information. At this point, much critical data is missing, such as the death rate among the infected people, the exact transmission rate, incubation period of the virus, and many other elements necessary to disarm the deadly microorganism.