Djibouti remains well-positioned, despite uncertainty

Geography is Djibouti’s key asset. Its strategic location in the Horn of Africa has lured global powers to establish military bases there, bolstering its economy and security. How much the country will continue to benefit will depend on regional stability, especially in Ethiopia and Somalia, as well as ethnic tensions domestically.

In a nutshell

- Djibouti’s location has attracted a foreign military presence

- This keeps the country secure despite both internal and external instability

- Regional tensions are unlikely to compromise Djibouti’s development

Thanks to its position in the Horn of Africa, at the southern entrance to the Red Sea, Djibouti has become key to understanding Africa’s security and economic outlook. Geography will remain a competitive advantage for this nation of fewer than one million people. However, regional tensions and internal instability may compromise Djibouti’s growth and its place as a strategic trade hub.

Formerly known as the French Territory of the Afars and Issas, Djibouti was founded in 1977 following an independence referendum. As its former name suggests, the history of this country – both before and after independence – has been shaped by tensions between the Somali-related Issa clan, comprising 50-60 percent of the population, and the Afar, comprising 40 percent of the population and found mainly in Djibouti’s north.

Because of the country’s desert climate, with poor soil and an annual average rainfall of 5.1 inches, both clans were traditionally nomadic pastoralists, scattered throughout Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somaliland.

Troubled past

As in other African countries, independence in Djibouti came before a national identity, and ethnic and clan identities determined political conflict and allegiances. While the Afar minority had been given an important role during French colonial administration, postindependence Djibouti was dominated by the Issa clans, albeit with a tacit agreement that the president should be an Issa and the prime minister an Afar.

Resentment among the Afar culminated in an armed insurgency in 1991.

Under the presidency of Hassan Gouled Aptidon (1977-1999), supported by the predominantly Issa People’s Rally for Progress (RPP), the country became an authoritarian one-party state. Resentment among the Afar culminated in an armed insurgency in 1991 against Mr. Aptidon’s regime, led by the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD).

The conflict was a low-intensity one and in 1994 both parties signed a power-sharing agreement. In 1999, Ismail Omar Guelleh succeeded his uncle as president. Though he has maintained a repressive state and kept control over the parliament and the military, Mr. Guelleh has managed to integrate important factions of the Afar clan.

Strategic location

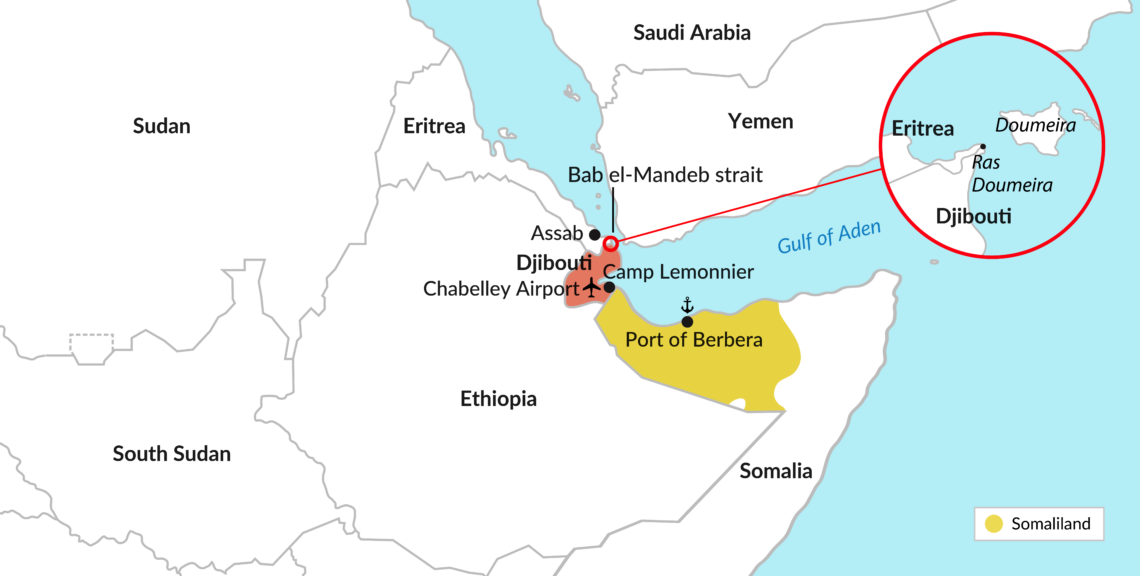

Besides ethnicity and clan politics, geography has also been key in shaping Djibouti’s political and economic outlook – for better or worse. Djibouti is bordered by Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, and separated from the Arabian Peninsula by the 20-mile Bab el-Mandeb strait. That makes the country a maritime trade choke point between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, and a strategic security hub in an extremely volatile region.

Geography explains why France, the United States, Italy, Germany, Spain, Japan and China all have forces stationed in the country. In the case of China and Japan, these were the first military bases built on foreign territory.

Location is Djibouti’s main strategic advantage.

In fact, location is Djibouti’s main strategic advantage. The country has little agricultural potential, very few natural resources and a low-skilled workforce (adult illiteracy is estimated at 65 percent). Lacking an industrial base, Djibouti’s economy is almost fully dependent on the services sector – which accounts for 80 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) –especially maritime port services.

Two factors have determined Djibouti’s economic growth rate, which has notched more than 5 percent in recent years: stable income from lease contracts with foreign powers, and the implementation of a massive infrastructure program, largely funded by Beijing.

Djibouti First

Because of its almost nonexistent agricultural potential, renting land to foreign powers has a low opportunity cost. The presence of foreign military bases can help reassure potential investors in an uncertain region. However, the underdevelopment of Djibouti’s economy, which only has a budding private sector, reduces impact these foreign bases can have in creating jobs for local suppliers.

Camp Lemonnier is the U.S.’s most expensive overseas base (with an annual rent of $63 million) and its only permanent base in Africa. The base is mainly an intelligence-gathering and counterterrorism center providing training to African forces in the war against Islamic militant groups, which Washington sees as the primary threat to American interests in the region. The U.S. also uses the Chabelley Airport to launch drone missions in Yemen, parts of Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Ethiopia and Southern Egypt.

Reflecting efforts to combine hard and soft power in its Africa policy and a long-term commitment to Djibouti’s economic growth, in 2014 the U.S. Congress passed the Djibouti First Initiative, which established contractual preference to Djiboutian goods and services supporting American efforts there. However, although a few Djiboutian companies have been awarded supply and construction contracts, the impact has been minimal. Djibouti’s private sector is too small and underdeveloped, and the business environment is poor (Djibouti ranks 171 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s 2017 Ease of Doing Business ranking).

The Belt and Road Initiative

China’s approach to Djibouti has been quite different. Beijing’s military support facilities in Djibouti are intimately linked to its economic ambitions. In its naval strategy, Beijing refers to the need for “near seas defense, far seas protection,” signaling a growing concern for the security and promotion of Chinese interests abroad.

Facts & figures

Chinese investments in Djibouti

China’s growing investment and military footprint in Djibouti is a direct consequence of the country’s place in Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For China, Djibouti represents not only a security hub but also a logistics, resupply and trade center, in a relatively stable country. Chinese investments, which go far beyond security concerns, make Beijing not only a lender of last resort for Djibouti but a privileged and attractive partner. China became Africa’s top job creator in 2016 and is now Djibouti’s largest foreign investor.

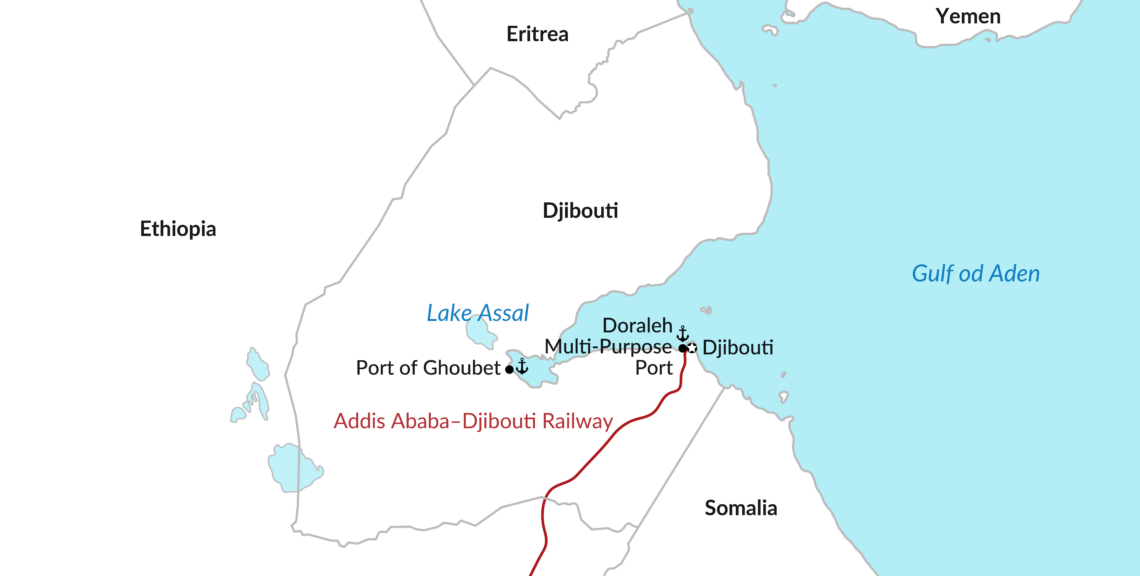

Through its Export-Import Bank, the country financed the construction of the Doraleh Multi-Purpose Port, with a handling capacity of 7.08 million tons a year; the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, the first electric transnational railway on the continent, which reduced travel times from two days to 10 hours; the Port of Ghoubet, which will function as a terminal to export salt from Lake Assal; and a water pipeline that will deliver 100,000 cubic meters of water per day from neighboring Ethiopia to Djibouti. Also, China Mobile International has selected the Djibouti Data Center as their base to facilitate network expansion, co-location and submarine fiber cable access services in East Africa.

These projects have the potential to transform Djibouti’s economy, even though (as opposed to the American approach) they do not directly address the concerns of local companies. The Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, for example, was conceived, financed and built by Chinese companies. In a country where water scarcity is linked to chronic poverty and ethnic tensions, the water pipeline, financed by Beijing’s Export-Import Bank, may significantly improve living conditions.

China’s investments in the country also represent tangible economic gains. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), mega-projects like the Doraleh Multi-Purpose Port and the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway are expected to support GDP growth of 7 percent in 2017-2019. Beijing is also financing the under-construction Djibouti Free Trade Zone, contributing to job creation in a country where labor force participation is less than 25 percent.

China’s security and economic approach to Djibouti aligns well with the country’s development plan, enshrined in “Vision Djibouti 2035,” to transform the country into a middle-income economy and a logistics and commercial hub for East Africa.

Threats to stability

Over the past decade, and despite some clashes between the regime and the opposition, Djibouti has reinforced its relative stability under the rule of Mr. Guelleh, who came to power in 1999 and was reelected to a fourth term in 2016. However, three factors may undermine the country’s perceived stability and economic potential.

The first is instability in Ethiopia. Djibouti is the gateway to Ethiopia, a vibrant but landlocked economy with 100 million inhabitants, and the country’s fate is directly linked to its neighbor. Clashes between the Oromo and Somali communities, increasing popular disapproval of the regime, and the government’s violent responses to public criticism may compromise Ethiopia’s “economic miracle” and weaken Djibouti’s prospects for growth.

The second is deteriorating regional security. Neighboring Somalia remains an extremely fragile and fractured state and acts as the operational base of al-Shabaab. The threat of maritime piracy in the Gulf of Aden is a concern, as is the conflict between Djibouti and Eritrea over the status of a hill called Ras Doumeira and the island of Doumeira, situated close to the strategic Bab el-Mandeb strait. After clashes between the two countries in 2008, Qatar stationed peacekeepers in the border region. But tensions recently flared up after Doha withdrew its forces.

Even under a worst-case scenario, the presence of foreign military forces would likely stabilize the situation.

The third threat lies in the relationship between ethnic Somalis (particularly the dominant Issa group) and the Afar. Although unlikely during a period of economic growth and political reforms, tensions between these two groups could resurface during economic deterioration or increased state repression. Despite Djibouti’s economic progress, the unemployment rate remains extremely high (estimated at 40 percent by the IMF). The national extreme-poverty rate is also very high, estimated at 44 percent in the country’s rural areas, which are home to a significant number of Afar communities.

Scenarios

While the political and economic situation of the country is somewhat fragile, Djibouti’s geographic advantage – part of what French historian Fernand Braudel called the “longue duree” of history – is likely to continue to determine the country’s future. Within this context, we should anticipate three possible scenarios.

The first scenario is that of mounting regional insecurity. Under this scenario, the region’s security and economy will deteriorate due to instability in Ethiopia and Kenya and/or a resurgence of piracy attacks along the Horn of Africa coast.

The slowdown of economic growth in Ethiopia, as a consequence of political unrest, would compromise Djibouti’s development and stability. This could be further aggravated by an increase in the flow of refugees and migrants through Djibouti, which is a crossroads for people escaping drought and violence in Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea and the brutal conflict in Yemen.

However, even under this worst-case scenario, Djibouti’s advantageous geographic position and the presence of foreign military forces would likely stabilize the situation. Increasing insecurity would reinforce Djibouti’s position as a base for evacuation, counterterrorism, counter-piracy and humanitarian operations. Ultimately, security-driven investments are resilient to conflict.

In the most likely scenario, Djibouti’s regional and domestic context will continue to offer both risks and opportunities. Areas of instability and regional tensions will persist but will not fully compromise growth or integration. Foreign powers will remain in the country, driven by both security concerns and economic opportunities. A political opening is unlikely, but the country’s strategic position and the security and economic interests of foreign powers are expected to sustain Mr. Guelleh’s regime.

Under this middle scenario, Somaliland and Eritrea may gradually weaken Djibouti’s regional influence. The Somali Port of Berbera is already attracting foreign attention and capital and will be home to a free trade zone, and the United Arab Emirates is installing military bases in Berbera and in the Eritrean port city of Assab. From a purely military perspective, technology is expected to decrease the rationale for establishing bases in foreign territory. But economic and trade interests will probably guarantee the presence of foreign powers in Djibouti.

In the best-case scenario, Djibouti would become a middle-income country akin to “Africa’s Singapore.” This scenario would entail an unlikely combination of regional stability, good governance and structural transformation, allowing Djibouti to fully reap the benefits of integration within East Africa and between African regions under the Belt and Road Initiative.