A tale of two pandemics

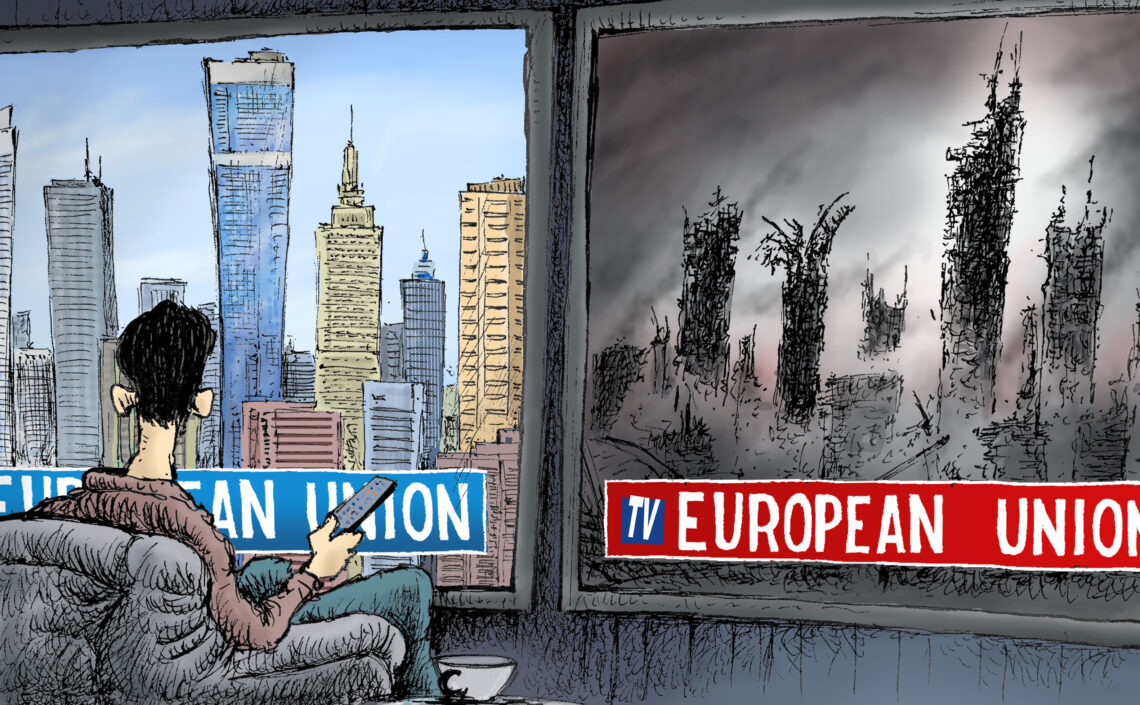

The future of the EU is heavily threatened by the Covid-crisis, according to critics. Or, quite to the contrary, it will prosper as EU leaders breathe new life into the European project. Which of the two narratives is more likely to materialize?

In a nutshell

- The European Union is having a bad pandemic

- The list of mistakes is long

- But so is the list of bold EU responses to the challenge

Two contrasting narratives concerning the impact of Covid-19 on the European Union are prevalent in Europe today. One depicts the epidemic as accelerating existing trends toward disintegration. The other sees the virus as enabling a leap forward toward greater integration.

Sky is falling

The first narrative, widely voiced by political leaders (for example, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte), journalists (including the editors of The Economist) and academics (drawing on the work of political scientists such as Douglas Webber, author of European Disintegration?), is potentially disastrous.

The European Union is having a bad pandemic and may end up collapsing, the reasoning goes. Covid-19 has given another potentially fatal twist to the multiple crises that have threatened the union since 2008. EU members responded to the epidemic in disarray, each determining its own strategy, without a thought for fellow Europeans. Initial bans on exports of medical supplies to other member states were quickly reversed but left a bad aftertaste. China, Russia, Cuba and even Albania reached Italy with medical assistance before EU members have managed to do so.

Most countries chose suppression strategies to stop contagion, imposing strict lockdowns, with heavy economic consequences. But Sweden opted to rely instead on the public’s supposed acquisition of immunity as contagion spread, while the Netherlands and Britain (still part of the single market and customs union) vacillated. National capitals, rather than Brussels, took critical decisions. Trust in the EU faltered, and euroskeptic nationalists claimed to be vindicated by border closures. As many as 67 percent of traditionally pro-EU Italians told pollsters that their country was disadvantaged by EU membership.

Some doubted whether this relaxation of the rules would remain temporary and feared the return of beggar-thy-neighbor economic policies.

The epidemic produced a deep recession, far worse than in 2008/2009, with each country providing financial support according to its means for stricken businesses and individuals. This exacerbated differences between a prosperous north and poorer south and raised debt forecasts dramatically. The risk premium on Italian government debt increased, despite the European Central Bank’s (ECB) 750 billion-euro emergency asset purchase program (PEPP). A ruling by the German Constitutional Court cast doubt on the ECB’s bond-buying program, risking an institutional crisis.

France, Italy, and Spain pushed for European solidarity in the form of debt mutualization and grants, a plan which the “frugal four,” Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden resisted. Subsequently, France and Germany agreed to a major recovery program which the European Commission formalized on May 27. But the overall amount was below expectations and opposition to the scheme’s grant elements will be vocal on June 19 when EU leaders are scheduled to debate the rescue package dubbed “Next Generation EU.”

The EU approved exceptional state aid, budget deficits and border controls as governments struggled to stop the spread of the virus while keeping businesses running and protecting citizens. This shook the EU’s pillars: the single market, the stability and growth pact, and the Schengen system of open internal borders. Some doubted whether this relaxation of the rules would remain temporary and feared the return of beggar-thy-neighbor economic policies.

The European Commission aimed for a coordinated exit from the lockdown but produced a road map for lifting coronavirus containment measures which, observers quipped, contained neither a road nor a map. Instead, it offered a list of principles, criteria, and recommendations which each country has interpreted in its own way. Italy decided in mid-May to reopen for tourists from early June, to the surprise of French competitors, while the commission tried to coordinate the revival of the tourism industry across the EU.

Covid-19 revealed the EU’s high dependence on China and India for medical and pharmaceutical products and its vulnerability to unforeseen obstacles in global supply chains. The epidemic inflamed relations between Washington and Beijing, casting further doubt on the future of the liberal international economic order in which the EU has been a key protagonist. Deglobalization and decoupling became the new watchwords, amid calls for greater self-sufficiency, state intervention in the economy (“industrial policy”) and the reshoring of jobs.

Climate policy, another European identity issue, is at risk because of the pandemic. The Greens were among the big winners in northern Europe in last year’s European Parliament elections and the European Green Deal is a signature policy of the European Commission that took office in December 2019. But voters, especially in southern and Central Europe, are more concerned with their livelihoods than with climate change, and their governments are unlikely to back stringent emission standards. This puts in doubt the notion of a “green recovery.”

This gloomy narrative sees the Covid-19 illness accelerating EU disintegration. But this is not the only possible reading of the pandemic’s impact on the EU.

The ambition of Ursula von der Leyen to lead a geopolitical commission faces new challenges in the times of Covid-19. Europe is caught between China and Washington and seems bent on propitiating Beijing. The EU’s soft power springs mainly from the attractiveness of its model and its provision of public goods, especially standards that set the conditions for commerce around the world. But an EU deep in a recession is straining to prop up its model. The classification by Freedom House, of Hungary, an EU member, as “partly free” and not democratic, lessens the EU’s once “magnetic attraction.” So far, the EU’s efforts to enforce respect for rule-of-law in Hungary, Poland and the Balkans have come to little.

This gloomy narrative sees the Covid-19 illness accelerating EU disintegration. But this is not the only possible reading of the pandemic’s impact on the EU.

Hardened by adversity

The dictum of Jean Monnet (1888-1979), the moving spirit behind European integration after World War II, that Europe will be forged in crises has been widely quoted since the onset of the pandemic. Despite diverse reactions among the 27 member states, the EU has taken several bold initiatives whose enduring benefit depends on containing the outbreak and mitigating its economic consequences. First indications, especially on suppression of the epidemic, are surprisingly encouraging.

The protection of human health is an EU objective, set out in article 168 of the Treaty of Lisbon; it includes such tasks as surveillance and preparedness for bioterrorism and epidemics. But the member states retain the principal responsibility while the EU’s main role until now has been to coordinate and persuade them to strengthen their rapid response capability.

Still, EU states were unprepared for the epidemic. France, for example, which had the largest stock of masks in the world in 2011, faced a shortage in 2020. This followed the dissolution of EPRUS (The Establishment for Preparing and Responding to Health Emergencies), under President Francois Hollande (2012-2017).

EU coordination encouraged the exchange of best practices among member states. Now, the commission proposes a major EU public health budget.

The European Commission stepped in to discourage initial bans on exports of personal protective equipment to other member states (albeit ill-advisedly prohibiting exports to most third countries). Soon member countries were providing each other with medical supplies and treating each other’s patients. The commission quickly launched the joint European procurement of personal protective equipment, improving supplies to the 25 participating member states. National authorities in Greece, Poland, and the Czech Republic, where the epidemic arrived later, learned from Italy’s experience and achieved better results. EU coordination encouraged the exchange of best practices among member states. Now, the commission proposes a major EU public health budget as a step toward creating a European “health union.”

After President Christine Lagarde’s shaky start, the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program and other initiatives (amounting to 7.3 percent of the eurozone’s gross domestic product) prevented the fragmentation of the eurozone and helped businesses absorb the shock. The ECB has not been deterred by the German Constitutional Court’s ruling questioning the legality of the ECB’s bond-buying program although this raised difficult institutional questions. The commission put forward an innovative scheme to help member countries protect jobs: “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE). The EU’s road map for recovery provided criteria for aligning national recovery plans with EU priorities – the single market, climate policy and the digital “transition.” Accordingly, for example, the French government demanded emission cuts from Air France as a condition for its 7 billion-euro bailout.

The relaxation of EU rules to help fight the pandemic does not necessarily imply permanent changes. EU ministers suspended but did not abolish the union’s 3 percent deficit spending limit so that governments can support health systems, businesses and workers. The commission’s more flexible approach to state aid takes the form of a temporary framework that expires at the end of December. Italy opened its borders in early June and others have announced similar steps. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have opened their borders to each other in a Baltic “travel bubble,” and the commission is encouraging remaining travel restrictions to be lifted, with safety measures in place, when health conditions permit. So, the Schengen system, which provides for exceptional circumstances, remains intact.

An agreement between France and Germany on the size and shape of an EU Recovery Fund revived cooperation between the two countries which have been the “locomotive” of European integration since the 1950s. The commission transformed this agreement into a proposal for a 750 billion-euro recovery fund, linked to the EU’s budget for 2021-2027. This scheme (“Next Generation EU”) involves raising funds through bonds guaranteed by the EU budget. These funds will then be distributed as grants and loans for meeting economic needs linked to the virus, as long as the expenditure is aligned with EU green, digital and other priorities. The bonds issued to fund this scheme will be repaid over a very long period and serviced partly by addition EU revenues, (“own resources”) such as a tax on large digital companies and a carbon tax.

Paradoxically, Brexit, itself involving partial EU disintegration, facilitated this major innovation, which London would have opposed. Without the UK, the “frugal four,” will struggle to obtain more than marginal adjustments, for example reducing the proportion of grants to loans, while maintaining their own budget rebates. Details remain to be agreed but the recovery fund clearly represents a significant step forward in European integration.

EU soft power still produces effects, despite the epidemic, whether in neighboring regions or further afield.

As to “mask diplomacy” euphoria in Italy over assistance from China and Russia: it has not outlasted the first deliveries of medical supplies and assistance, which occurred before mutual aid among EU countries got underway. The EU quickly mobilized a 3.3 billion-euro assistance package for the countries of the Western Balkans and extended to them its arrangements for combined procurement of personal protective equipment. A joint summit meeting by videoconference on May 6 noted that EU support and cooperation “goes far beyond what any other partner has provided to the region, (and) deserves public acknowledgment.”

Serbian President Alexandar Vucic gave such an acknowledgment the next day. He welcomed support from the EU, the United States and China and declared that “Serbia is committed to the West.” Mr. Vucic exemplifies democratic backsliding and geopolitical maneuvering in the Balkans. Nonetheless, EU membership, albeit distant, remains the goal of all countries in the region.

EU soft power still produces effects, despite the epidemic, whether in neighboring regions or further afield. The EU’s geopolitical influence takes the form less of security and defense (which member states tend to oversee themselves, despite recent initiatives) than of the provision of public goods, including product and process standards. The commission acted geopolitically when it encouraged European governments to buy stakes in companies to prevent takeovers by Chinese state-backed enterprises. It is acting geopolitically when it pushes back against unilateral U.S. sanctions on Iran or maintains pressure on Russia over Ukraine. It is acting geopolitically when it allocates resources to fighting the coronavirus in developing countries and calls for a global response. EU climate and digital policies also have geopolitical dimensions.

The two narratives briefly examined here cast light on different aspects of the EU in the times of Covid-19. Euroskeptic nationalists typically propagate claims of EU failure but have been rather subdued during the pandemic as mainstream governments have taken over their trademark policy of closing borders to foreigners. Nonetheless, the grip on power of several pro-EU mainstream leaders, including President Emmanuel Macron in France, Prime Minister Conte in Italy and Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez in Spain, remains tenuous.

Pro-Kremlin and pro-Beijing sources of disinformation stir up perceptions of EU disintegration as do politicians who predict collapse, if their particular desiderata are not met. Covid-19 has encouraged both greater national autonomy and more sophisticated forms of EU solidarity and cooperation. The pandemic reinforces the observation of political economist Erik Jones that both integration and disintegration may be occurring at the same time.