From inflation to higher taxes

Inflation is rising, and while that would be easy enough to handle under normal circumstances, today’s situation is far from normal. The heavily indebted governments of the U.S. and Europe will almost inevitably have to turn to higher taxes to resolve the problem.

In a nutshell

- Inflation has begun rising rapidly

- Central bankers do not want to raise interest rates

- Europe will raise taxes first; the U.S. will soon follow

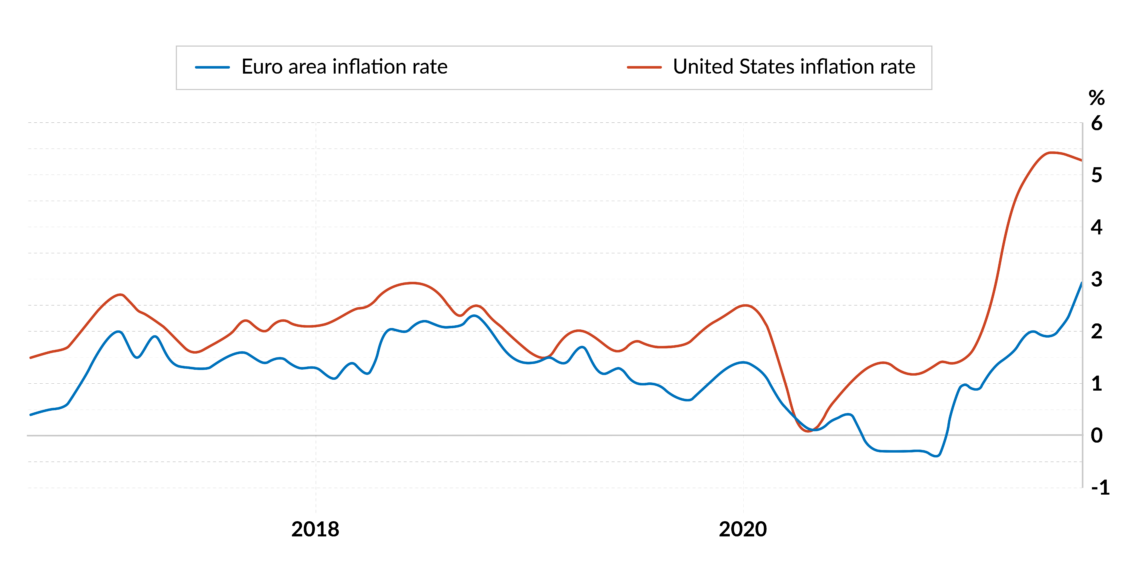

After a decade of blithe money printing, Western central bankers have finally achieved their target: inflation has moved beyond the 2 percent threshold in Europe and the United States. In fact, prices are growing faster than expected. The latest Eurostat data shows that annual inflation in the euro area is about 3 percent (up from 2.2 percent in July). In the U.S., annual inflation is well above 5 percent, and consumers expect it to rise further over the next 12 months.

Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic pretend that everything is under control and that the inflationary spikes are a flash in the pan. The European authorities tend to blame the allegedly temporary rise in energy prices, while the Americans frequently refer to the (also short-lived) supply-chain and labor-market bottlenecks.

Both the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve Board, however, have not offered clear indications about the next steps they will take. ECB president Christine Lagarde seems more interested in launching the digital euro and using the money supply to sustain the banking industry and tackle public indebtedness. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell keeps announcing the beginning of less profligate spending but also confirms that interest rates will stay low for a very long time. The interest rate on the 10-year U.S. Treasury is currently about 1.3 percent – less than 4 percent in real terms, about the same as the real yield of the German Bund.

Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic pretend that everything is under control.

The central bankers’ relaxed response to rising inflation has important consequences that could lead to a range of different outcomes. This report analyzes some of the possibilities for the U.S. and the eurozone.

Awash in cash

In the U.S., inflationary pressures appeared earlier and are more pronounced. Americans’ expectations about inflation over the next five years support Chairman Powell’s confidence that he can keep interest rates low. While Americans know that inflation is high and could grow, they also believe that it will soon fall back to about 2 percent.

This explains why investors keep buying large amounts of treasuries (a substitute for bank deposits), why the real estate market is booming (cheap mortgages) and why Wall Street remains healthy: plenty of people remain willing to buy stocks. All of this attests to optimism that the economy will continue to bounce back. The big question is whether that optimism rests on a solid foundation.

The answer is mixed. The good news is that the U.S. economy has recovered very quickly from the Covid-19 crisis. The International Monetary Fund now predicts gross domestic product (GDP) will grow by 7 percent in 2021 and almost 5 percent in 2022. People are awash in cash, and the surge in stock prices makes them feel richer – the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen 32 percent over the past three years.

Facts & figures

Some of this perceived wealth goes into the real estate market, some feeds Wall Street, and the quick recovery encourages large sections of the population to increase spending on consumer goods and services. In turn, the surge in demand has spurred producers to expand production by exploiting spare capacity and taking on new investment projects. Investments are up by 15 percent in nominal terms. New investments often incorporate state-of-the-art technology, so significant productivity gains may be just around the corner.

Inevitable inflation

One might therefore feel reassured. Inflation is inevitable when abundant liquidity stimulates demand and producers adapt at a slower pace, but once production catches up, many believe it will disappear.

However, there are some reasons for worry, as illustrated by four main questions:

- What if stocks stop rising and people realize that higher share prices no longer offset the losses associated with staying liquid?

- What if inflation is not tamed fast enough, and the American public changes expectations about future price rises?

- What if geopolitical tensions lead to global uncertainty, investments freeze, and growth rates drop below expectations?

- What if real wages start growing? (Average U.S. wages have risen slower than inflation, effectively cutting pay by 2 percent over the past year.)

The answers to these questions are unlikely to be positive for the inflation outlook. For now, the overall picture for the coming months will most likely be characterized by lower growth accompanied by relatively high, stable inflation. The slowdown in GDP is already palpable: some blame the new Covid variants, while others point to the shortage in computer chips and the lack of cheap, motivated workers.

These explanations all contain grains of truth. The main takeaway, however, is that producers are hesitating to engage in ambitious, long-term projects, while heavily indebted companies are refraining from expanding production until they see that interest rates stay put. If individuals unload liquidity by buying goods while supply increases at a slow pace, inflation fills the gap.

Appeasing Wall Street

In this context, two scenarios emerge. If the Fed wants to fight inflation, it will stop printing money and accept markedly higher interest rates. It would go from slowing down its purchases of government bonds (known as “tapering”) to an outright freeze. That would hit many indebted companies and consumers. It would also become more difficult – and therefore more expensive – for the government to sell treasuries.

If the Fed wants to fight inflation, it will stop printing money.

The upshot is quasi-stagnation, rising unemployment and persistent inflation. Taming that beast takes time, especially after 10 years of generous money printing. The situation would be painful and hard to accept for the Biden administration, whose policies depend on ample public spending.

A second scenario would see the Fed kick the can down the road and hope for the best. This is the most likely outcome, as the recent debate about Chairman Powell’s possible reappointment shows. The main difference between the two factions in the Senate is their stance on whether the Fed should increase the money supply only moderately in 2022 or do “whatever it takes” to keep the economy humming. Low interest rates remain a priority to make Wall Street happy. Officials will then blame the Covid variants for slow growth and inflation, and tell Americans that a crash in the stock market would be much worse than a few percentage points of “transitory” inflation.

High-tax future

Europe is heading in a similar direction. In contrast with the prevailing sentiment in the U.S., Europeans see rising inflation as a longer-term phenomenon but not as a significant threat. They are concerned about fiscal discipline, the sustainability of public debt in some key countries and the future of the welfare state in general.

The ECB will happily print new euros and buy all the government bonds it takes to keep economies afloat.

In recent years, the answer has come from the ECB, which bought colossal quantities of treasuries, either directly or by offering guarantees and privileges to the banks willing to roll over government-issued debt. Yes, inflation is coming, but the European authorities have their answer ready: Higher taxation and more modest state pensions will balance government budgets, while inflation will erode the public debt.

Unlike the U.S., the strategy is clear: the ECB will happily print new euros and buy all the government bonds it takes to keep economies afloat. The rest plays a secondary role and will become a matter of fiscal policy, which means higher taxes.

The West has enjoyed the illusion of a free ride for over a decade, but inflation is about to expose the several imbalances that policymakers have so far swept under the rug. Of course, low, or even moderate inflation is not an insurmountable problem. Yet, it can have dramatic consequences if it operates within a context of distorted financial markets, where central banks are committed to keeping nominal interest rates close to zero and may well force them further down by introducing their own digital currencies.

Certainly, the U.S. and Europe are not facing the same problems. They have different degrees of tolerance and expectations in terms of growth, public expenditure and unemployment. They have also chosen different scapegoats and targets.

Nonetheless, if these economies want to avoid a healthy but painful crash, there is only one main, discouraging option: higher taxation to rein in fiscal imbalances and cool off private demand. Europe is leading the way, America.