Covid-19 and Leviathan – the German case

Large parts of the world are still in the grip of severe economic and health crises. Many hope that, with effective vaccines, both issues will abate. But in Germany, the level of government intervention starkly increased with the pandemic.

In a nutshell

- Government intervention has skyrocketed during the pandemic

- Some measures are unlikely to be rolled back

- The German public often favors centralized decision-making

A look at economic and political history shows that big government is very often the result of crises like wars, recessions, natural disasters or pandemics. But even after these events subside, government power does not. Once governments assume new roles, creating agencies, authorities or taxes, they are very unlikely to dismantle them once a crisis subsides. And citizens often get used to being “cared for” in this manner – taking government authority, tutelage and subsidies, and even higher debt and taxes, for granted.

There are some notable counterexamples. When governments were blamed for worsening or even creating crises, this sometimes provided the opportunity for political reformers and entrepreneurs to make big changes. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1979 is an example of this; so is German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard in 1948 or even Chancellor Gerhard Schroder in 2003. But most emergency measures outlive their usefulness. In Germany, a 1902 tax on sparkling wine to finance Kaiser Wilhelm II’s war fleet is still in effect. Higher-income brackets still need to pay the “solidarity surcharge” to support the “urgent” task of German reunification.

Will today’s emergency measures follow this pattern, and the post-Covid world defined by “Leviathan” states? To assess this question, three aspects should be considered: state budgets (expenditures, taxes, debt), economic regulations and control over citizens’ lives.

Expanding welfare state

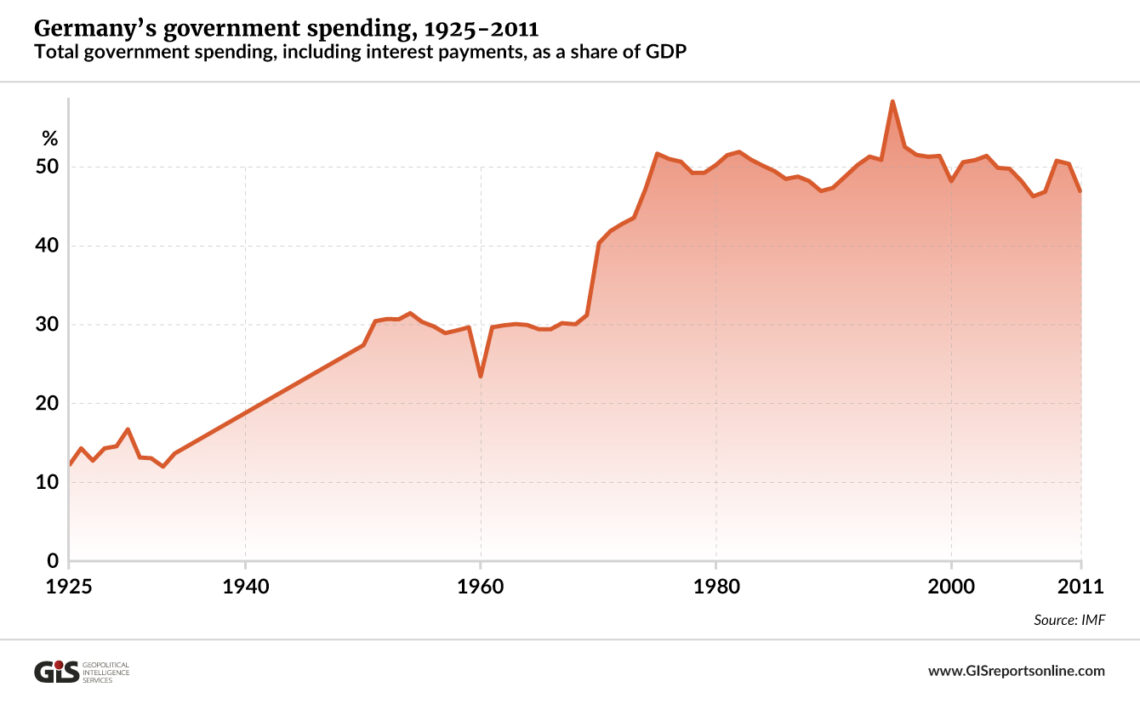

The last 100 years in Germany tend to confirm the Leviathan hypothesis. Before World War I, government expenditures were well below 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), partly as a consequence of fiscal sanctions imposed by the Versailles Treaty. With National Socialism and World War II, public spending and government debt naturally skyrocketed. But despite enormous economic growth during the 1950s and 1960s, public expenditure never returned to prewar levels. And it took only relatively mild economic setbacks, like the oil crisis and an ideological shift toward Keynesianism in the 1970s, to lead to an enormous increase in public spending, which was mainly financed by debt.

The idea that some public expenditures could be scrutinized under an emergency regime was never entertained.

German reunification was seen as a mostly welcome emergency that justified more taxing and spending to support the collapsing East German economy. But also, this “triumph” of capitalism over socialism did not help to slim down Leviathan for Western Germans. In terms of the tax burden and social security charges, Germany, Belgium and France have now overtaken Scandinavian welfare states and compete for the top position among OECD countries. Germany holds the top spot, with a record 45 percent of all government expenditures going to social measures.

Whereas taxes and social security systems require public debate and new legislation, public debt is a readily available tool to react to an unforeseen crisis. There was no concerted call to either raise or lower taxes in Germany when the pandemic struck. The consensus was to spend by allowing the deficit to rise. At the beginning of 2020, Berlin was in a relatively comfortable position, with budget surpluses for some years, a declining debt-to-GDP ratio and borrowing rates often in negative territory. But even without Covid-19, debt would have been on the rise again.

State budget

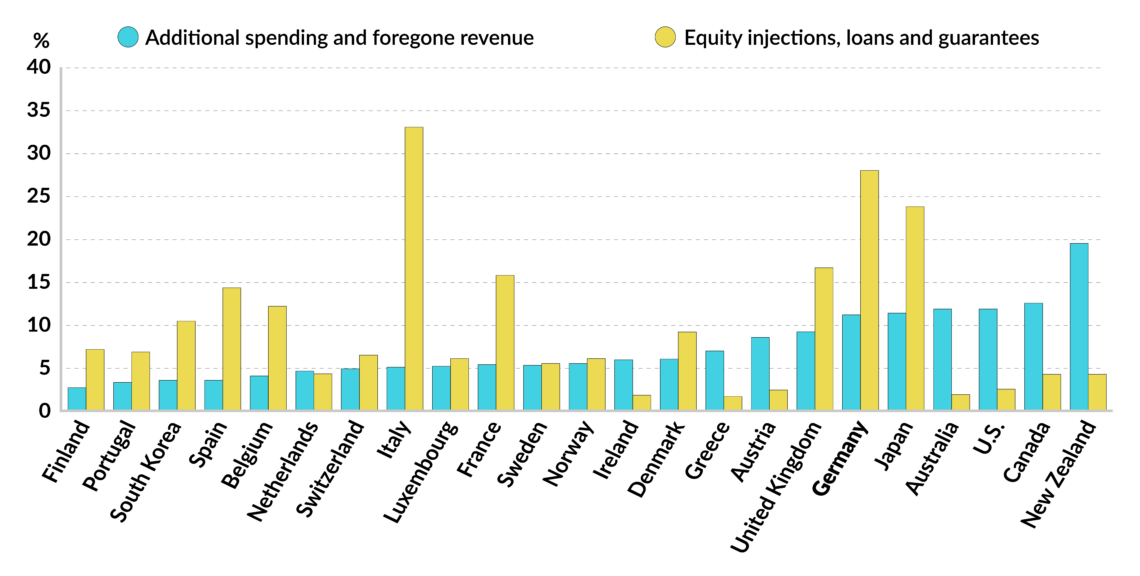

Last year, the German state had to borrow 140 billion euros – approximately 5 percent of its GDP. This year, the federal government alone plans a deficit spending of around 180 billion euros, to which 50 billion may be added. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the German economy contracted by around 5 percent in 2020. Economic growth is expected to pick up in 2021 as vaccines become widely distributed, but output is not projected to return to the precrisis level before 2022. This by itself implies a huge hole in the public purse as a consequence of lower tax receipts.

Crisis spending has increased more than in most other advanced economies. Most of it seemed reasonable (for example, scaling up medical infrastructure) and effective in preventing an even worse economic downturn (expanding short-term work benefits, providing liquidity to firms, and expanding loan guarantees). Last year the government implemented a temporary cut to value-added tax (VAT). Whether it boosted consumer demand or reduced business costs is debatable. The cut expired as planned at the beginning of this year, which goes to show that when it comes to tax cuts, governments are always likely to keep them temporary, but when it comes to tax increases, they can be counted on to make them permanent.

Facts & figures

Overall, the EU expects German government expenditures to have risen to 52.2 percent of GDP in 2020. This year also, half of the German economy is likely to be more or less directly “state-financed.”

At the same time, the idea that some public expenditures could be scrutinized under an emergency regime was never entertained. The Social Democratic finance minister (and the party’s top candidate for this year’s general elections) Olaf Scholz happily handed out extra money for green and leftist projects, without being hampered by his so-called conservative boss, Chancellor Angela Merkel, and her Christian Democrats. For example, the current cap on photovoltaics, which sets a limit on government payments for solar energy that is fed into the grid, will be abolished, and some 7 billion euros will be spent to make Germany a world leader in hydrogen technology. Also, extra pension subsidies for 1.3 million people will be handed out, costing taxpayers some 1.5 billion euros each year.

Who needs rules?

This spending spree was made possible by the relatively sound budget at the beginning of last year – which, in turn, was also the result of Germany’s debt brake, a constitutional law requiring a balanced budget. This rule allows for exceptions during emergencies like the current pandemic. However, many proponents of deficit spending, even in Ms. Merkel’s center-right party, used the crisis as an opportunity to demand that the rule be abolished. This would require an unlikely two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament. A prolongation of the emergency clause allowing abnormal deficits, however, seems likely even long after the crisis.

Much of government spending on subsidies for firms or people who could not work during lockdowns is justified. However, it is almost impossible to prevent credit misallocation to “zombie” firms that would and should have disappeared from the market even without the pandemic. The question is whether this support will go back to precrisis levels, or whether many nonviable businesses will remain on the list of those who “need” and “deserve” this lifeline. Politically, the most likely answer is the latter. Especially in a year with federal and state elections, no political party will want to be seen as indifferent to the plight of beleaguered businesses.

Basic freedoms

As in most other countries, the German government reacted to the outbreak of the pandemic with emergency measures that strongly curtailed private property rights and basic freedoms. These measures were based on the scientific advice of epidemiologists rather than economists. They were put into law in an often hasty, but formally correct manner, and widely supported by the public. Opinion polls suggest that many citizens were in favor of even stricter rules than those that were implemented.

This must not be taken as proof of an enduringly subservient spirit in German citizens; it is rather a reasonable expression of trust in experts and institutions. However, the current discussion on how to return to basic freedoms is concerning. Although the vaccine rollout has been embarrassingly slow, there has already been a debate on whether immune individuals should have the “privilege” to travel, shop and meet in groups. It is dangerous for a society to see basic freedom as something that has to be granted by the government rather than a fundamental right.

The German judiciary has performed its task with unrelenting vigilance.

Germans also adopted a similar attitude to federalism and decentralization of powers during the crisis. Foreign and domestic observers were understandably confused by the discrepancy in regional lockdowns. But infection rates and hospital capacities differed enormously across the country. The different policy responses were not only proportionate, but they also allowed regions to learn from others’ experience. However, the federal government as well as most media and citizens were actively calling for a more centralized one-size-fits-all policy, dismissing decentralized responses as an unsightly patchwork.

Shifts in power balance

The balance of state powers has also come under strain between the executive and parliaments on both the federal and state levels. During emergencies, the executive typically takes the lead, as it has to react swiftly to unforeseen circumstances. But because most ordinances and bylaws pertaining to Covid-19 measures must be ratified and executed on the state level, Chancellor Merkel and her federal “Corona-Kabinett” could not directly issue decrees like French President Emmanuel Macron, for example.

Instead, a committee has become the main steering board of the Federal Republic during the crisis. The Conference of Ministers-President (MPK), consisting of the chancellor and the executive leaders of the 16 German states, effectively decides on the next emergency measures. The meeting usually ends after many hours of haggling on Zoom, with more or less binding decisions agreed among leaders. Then the Bundestag and state parliaments are notified and invited to debate; but the package deal has already been made, with no realistic way to change it in parliament. This collusion among executive leaders has been going on for a long time. The crisis provides some justification for such procedures – but they could easily become customary in normal times.

Meanwhile, the German judiciary has performed its task with unrelenting vigilance. Several Covid-19 ordinances were struck down by courts, mostly regional. They operate by weighing individual liberties as enshrined in private and public law against the aims and means of administrative acts. The main benchmark is the principle of proportionality: Is a law or regulation that curtails individual rights effective, necessary to produce the desired result, and proportional to the infringement of personal rights?

Some measures did not meet these standards and were overturned by local and state courts: a regional ban on drinking alcohol in public, a ban on any travel beyond a range of 15 kilometers from one’s home and a statewide curfew at night, to name just a few.

Scenarios

The Leviathan state does sometimes recede, but more often it gains strength. Mostly this happens gradually and imperceptibly. During a crisis as severe as the one we are experiencing, however, a rapid expansion as a response to an emergency can be widely accepted. Often, this leap forward in state power becomes permanent. Both politicians and citizens will get used to this new state of affairs.

Under the most likely scenario, 2020 and 2021 will be considered anni horribiles in Germany and elsewhere. The increase in government spending will lead to a substantially higher level of public debt and eventually higher taxes.

Regulations and state interventions will become the norm. Industrial policy aimed at picking the winners and protecting the losers of globalization and structural change has become fashionable again, both in Berlin and Brussels. Attempts to create “strategic autonomy” for key industries have often included not only protectionism but even calls for nationalization, for example of pharmaceutical industries or hospitals.

The crisis will likely further weaken federalism and democratic accountability in Germany. Whereas the rule of law still seems in good hands with German courts, the increase in the powers of the executive and the federal Chancellery will remain, since citizens tend to prefer centralized direction over decentralized experimentation.

Over the last 12 months, Germans have shown high levels of trust in their government, and a remarkable willingness to follow state orders. The general belief that the state ought to take care of important matters seems to have been strengthened.

Former U.S. President Obama’s chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, once said: “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is an opportunity to do things you think you could not do before.” This is how many anti-capitalist and environmental activists see the current situation. And they have been emboldened by the pandemic in their attempt to declare climate change another state of emergency. Given Germans’ romantic attachment to anything related to nature and their reliance on the state to do the right thing, the powers recently enacted are likely to stay. The Leviathan state will not disappear after the pandemic; it will simply serve another purpose.