The art of creating an environment for healthy longevity

Longevity research shows that the building blocks of a healthy life are developed early and cultivated throughout the years. Centenarians tend to have a sense of purpose and access to resources. A lucky draw in the genetic pool lottery plays only a secondary role.

In a nutshell

- An ecosystem of wellness can vastly extend years of good quality life

- The ballooning public healthcare expenditure of ageing can be tamed

- The health-promoting strategies of centenarians can be mastered at any age

Modern medical research has brought us to an important juncture. Health professionals are now capable of developing an environment for healthy longevity – a system designed to benefit both the personal well-being of patients and the economy at large. As a society, we need to start seeing longevity through a new lens and understand how it affects economic matters.

Culturally learned longevity

In my research with over 300 healthy centenarians – individuals of one hundred years of age – from Italy, Costa Rica, Cuba, Uruguay, U.S. and other countries, I initially looked for genetic factors as the main ingredient of long-lasting health. I have learned, however, that genetics only account for some 20 percent in the components of longevity, a conclusion that other researchers (for example, demographer Dan Buettner of the New England Centenarian Study, or Harvard University and Stanford Center on Longevity Professor Ellen Langer) have also reached. Given these findings, my focus shifted to investigating other elements that characterize the unique individuals who defy the established premises of conventional gerontology.

I now differentiate between growing older, the passage of time, and aging as distinctive terms that reflect the cultural beliefs associated with the process of advancing in one’s years. Those ingrained convictions contribute more to an individual’s healthy longevity than the factors emphasized by conventional science, such as geography, climate, diet, and genetics. Although these circumstances may have some impact, they do not fully explain why some people grow old in good health and many others do not. Thus, in my work, I operationalize growing older as primarily the passing of time, whereas aging is highly affected by the assimilated cultural beliefs about longevity and sustained wellness.

Many centenarians eschew the usual recommendations of preventive medicine – yearly physicals, vaccinations and regular visits to doctors for minor health issues.

In my view, the building blocks of healthy longevity are cultural. They include the beliefs held by individuals on matters such as esthetics, ethics, religion, illness, wellness, kinship, socialization, and time.

Interestingly, even though cultures uniquely interpret each of these essential concepts, I have found a common denominator that I call individuated beliefs. Centenarians tend to approach their culture’s norms more as outliers than subscribers to commonly held views.

For example, although centenarians tend to think of wellness similarly, they broaden the scope of the general concept embraced in their cultures to fit their individual needs, based on personal experience.

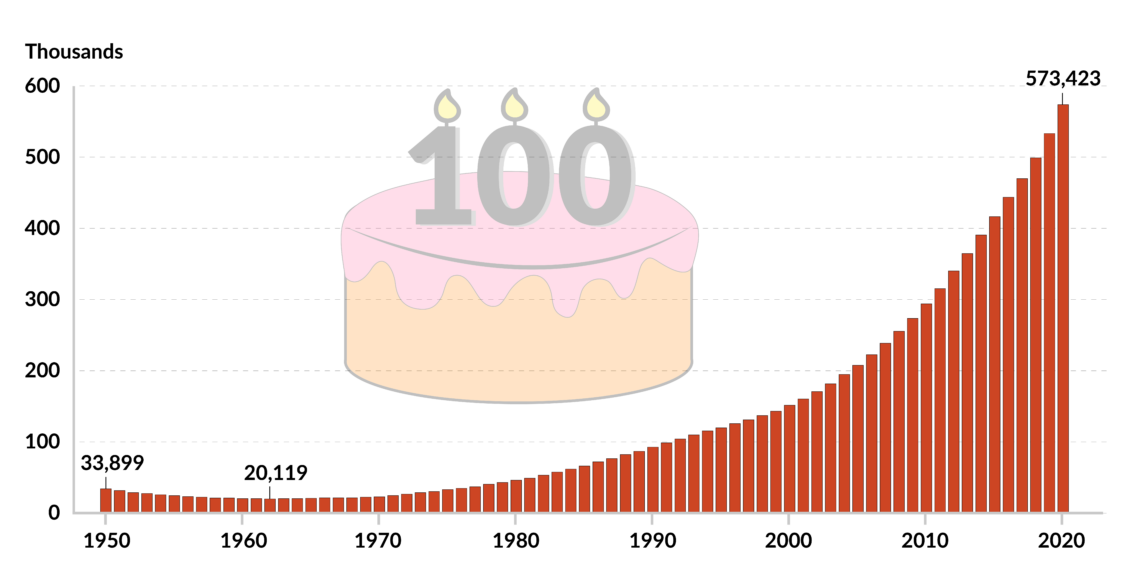

Facts & figures

The world’s supercentenarians

- Kane Tanaka from the Fukuoka prefecture is 117 years old, making her a so-called supercentenarian: a person living to or beyond the age of 110. She has become the world's oldest living person following the death of 117-year-old Chiyo Miyako in 2018 and is presently the eighth-oldest person to have ever been confirmed to reach such an advanced age.

- The oldest man alive is Robert Weighton from the UK, at 112 years old. Jiroemon Kimura, who died in 2013 at the age of 116, was the world’s oldest verified male in history.

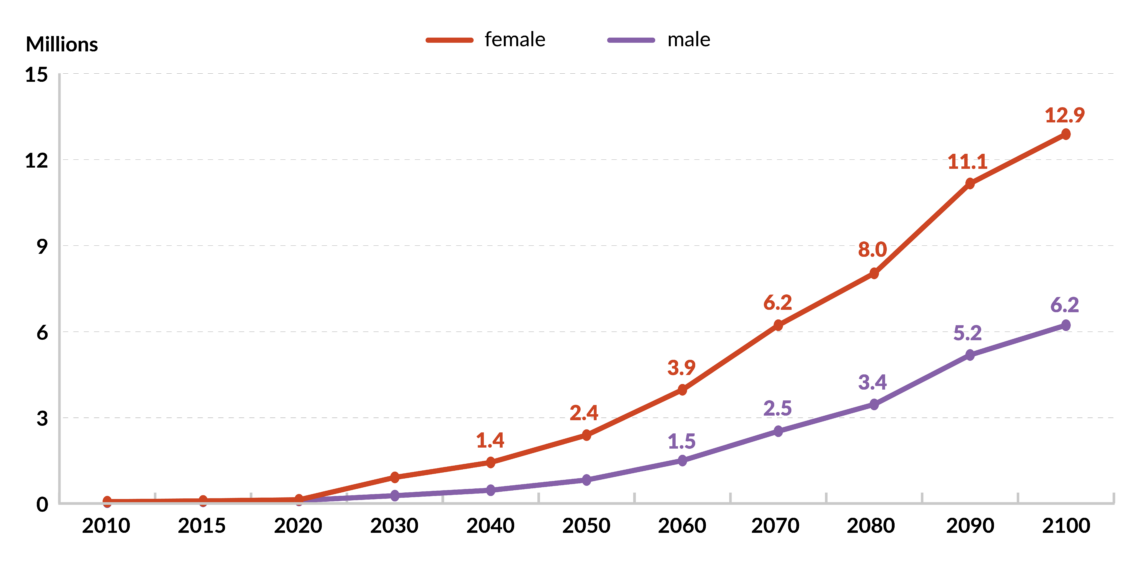

The economics of longevity

The cost of healthcare for individuals, organizations and governments has become alarming in developed countries, chiefly because it grows as medicine advances. Most importantly, the cost of medical care is the highest for the elderly, feeding the perception that aging must inevitably lead to mental and physical degradation.

My research shows that most centenarians remain healthy as they age. And this is not attributable, for the most part, to medical intervention. Many centenarians eschew the usual recommendations of preventive medicine – such as yearly physicals, vaccinations and regular visits to doctors for minor health issues.

Their preference for minimal medical supervision often results from external conditions – as many of the centenarians live in rural areas without much access to medical services – but also from their interpretation of adversity. Centenarians tend to rely on what they perceive as the inherent wisdom of the human body, mind and emotions during their long lives. They view hardship as a challenge and they thrive by tackling it head-on.

Even as trends in healthcare create new ways to improve the cost-to-life-quality ratio, the system as a whole remains inimical to sustainable wellness. Lately, there has been a discernible shift away from fee-for-service models to value-based reimbursements. Yet globally, the dominant healthcare model remains based on reductionist methodologies that focus on diagnostics and pathology management.

There is little room in the current system for stimulating health and longevity based on wellness and data from modern epigenetic research (which relates to nongenetic influences on gene expression).

The main components of the code system help balance wellness with productivity and accountability with teamwork.

Population-based healthcare systems create savings for the patient, the provider and the payer when the statistical effectiveness of the services rendered can be demonstrated. However, as chronic disease rates continue to trend upward around the globe, the cost of care increases as well. To overcome this challenge, healthcare systems ought to reform their practices and business models, and go beyond the management of illness. What is needed is a much broader focus on healing and wellness – among healthcare providers, and the business and administration sectors as well.

Health and organizations

Organizations can apply new principles of “centenarian consciousness” with the help of my Empowerment Code model. It helps businesses of all sizes improve employee well-being and company performance. The main components of the code system are grounded in a “navigational compass” that helps balance wellness with productivity and accountability with teamwork.

Facts & figures

By empowering employees (providing them with access to the resources needed to complete tasks), a company may help them find more meaning and purpose in their work. This is a better metric than “happiness at work,” which research has shown to have little correlation with wellness and productivity. (Employees can be quite happy at work without necessarily being healthy or productive. My research shows that the opposite can also be true – healthy and productive people can be miserable in their places of employment.)

In the Empowerment Code system, individuals who add meaning and purpose to a team are given more control as a “unit of local intelligence” to solve problems and continually make improvements throughout the company. The design of the Code model is based on the workings of the most resilient system, one that every second makes hundreds of thousands of decisions under adversity – our immune system.

Drain on productivity

In my work with upper management in Fortune 500 companies, I introduce a concept I named “shadow costs” to describe factors that deplete productivity but remain undetected by profit and loss metrics. These hidden costs include what can be described as “retirement consciousness,” brain fog, brain drain, and adverse effects on the learning curve.

Let us look more closely at “shadow costs” and how disempowerment (imposed helplessness) adds to them. Retirement consciousness is a mindset where one’s sense of meaning, whether at work or home, is suspended until the time of an idealized liberation from work. Productivity and wellness are undermined in this mindset. In my work with global organizations, I have found out that retirement consciousness can start as early as a decade before retirement age. When it occurs in management, the company’s effectiveness is hampered due to the reduced creativity of its leaders, their dislike of change and aversion to even the most rudimentary risk-taking.

This loss of accumulated competence burdens companies with ‘shadow costs’ when they need to replace employees.

Interestingly, centenarians seldom think of retirement. When compelled to retire, they shift their interests and become active in other fields.

Brain fog is a cognitive deficit that negatively affects task focus and problem-solving. Also, it increases one’s proneness to accidents. The problem often afflicts people with chronic illnesses who take interacting medications with strong side effects. Centenarians, however, remain cognitively intact throughout their long lives and seldom suffer from chronic diseases.

Brain drain diminishes productivity and often prompts early retirement. This loss of accumulated competence burdens companies with “shadow costs” when they need to replace valuable employees. The process also overloads other employees who need to pick up the slack until the cadre becomes fully operational. Reduced company productivity is the result.

I posit that centenarian consciousness – an attitude that challenges in life can be turned into opportunities – may be learned at any age and help prevent “shadow costs” at work while supporting wellness in private life. There is an additional social benefit to that.

As healthy individuals retire, they can turn to new interests and share their accumulated wisdom with their communities, consequently reducing the overwhelming cost of healthcare for senior citizens with chronic illnesses. I argue that most people develop disorders in the workplace predominantly for three reasons: responsibility without corresponding authority; a lack of resources to overcome challenges; and the loss of a sense of meaning. When such disempowering environments endure, they produce helplessness. This state, in turn, can lead an individual’s hereditary immunological deficiencies to trigger gene expression of family illnesses. I should note, however, that such congenital deficiencies are only propensities, not genetic sentences.

Creating a longevity environment

The type of empowerment that I aim to foster requires a paradigm shift in cultural beliefs and thinking. We need to move away from the concept of genetic sentencing and differentiate the process of aging from merely growing older. Also, we need to accept that meaning and purpose in life are powerful immunological enhancers. And then, we need to act on these concepts and values.

Additionally, rather than focusing on specific behavior changes, we should identify environments that discourage unwanted behavior and support desired outcomes. Here is where the concept of ecology comes in most useful: behavior is enacted in cultural contexts and influenced by an interplay between one’s self and the external conditions.

Research in the field of psychoneuroimmunology (or PNI) queries how thoughts and emotions affect the regulation of nervous, immune, and endocrine systems of the human body. These studies consistently show that acts of shaming increase the secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) cytokine and other pro-inflammatory cells in the victim, as if the immune system was responding to external pathogens rather than to shaming words.

In individualist cultures, shaming a person causes a biological response.

To me, a fascinating insight of that research, however, has been that members of the individualist cultures, such as those in the U.S, the United Kingdom or Australia, respond differently to shaming admonitions than representatives of the collectivist cultures (e.g., Japanese, Korean and Chinese).

In individualist cultures, shaming a person causes a biological response. For collectivist cultures, criticism needs to be perceived as shaming a family or a group before there is an inflammatory PNI response. It is worth noting how frequently children at home and employees at work are exposed to shaming as a behavior-modification tool.

Hard data shows that inflammation is one of the most prevalent conditions in several illnesses, including depression, cancer and autoimmune disorders. Recognizing how centenarians perceive adversity and keep their existence meaningful is the first, critical step toward implementing better strategies in life.