Is Brexit inevitable?

Signs are accumulating that the preliminary divorce agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union is starting to unravel, and that a year from now, on March 29/30, 2019, we could witness a “hard Brexit” with no transition arrangements and chaos in areas hitherto regulated by the EU.

In a nutshell

- The EU and UK remain at loggerheads over a transition deal after Brexit

- A “bespoke” deal giving the British financial sector special rights is not on the cards

- Revoking the UK withdrawal declaration or a second Brexit referendum are unlikely

Evidence is steadily mounting that Brexit will have a negative impact on the economies of the United Kingdom and the European Union countries, and time for softening the blow is running out.

The European Commission has set October 2018 as the deadline for completing exit negotiations, a date chosen to leave enough time for parliaments to approve any deal before Britain leaves the EU at midnight between 29 and 30 March 2019.

But the October deadline is looking increasingly unrealistic. The negotiations will probably go down to the wire. The two sides’ red lines are far apart and leave them little room for maneuver, raising the risk that Britain will crash out of the EU without an agreement.

Many companies are basing investment and relocation decisions on a worst-case scenario to avoid being caught out a year from now, if politicians fail to deliver the “smooth and orderly” Brexit that British Prime Minister Theresa May promised just a few months ago.

Transitional arrangements

The immediate way to limit, or at least postpone, the damage is to agree by March on transitional arrangements. These would bridge the gap between formal exit from the EU and a new permanent framework for future relations. The EU proposes that the transition period run until December 31, 2020, the end of the EU’s current budget planning period. It would thus last for 21 months after Britain leaves the EU.

In practice, though, it takes far more time to negotiate, approve and implement a long-term agreement, which implies that the transition should be open-ended. The British government appeared to recognize this in mid-February, hoping thereby to head off pressure to delay or reverse Brexit. Open-ended transition is likely to be opposed, however, by diehard Brexiters and by some in the EU.

Last month, ministers from all 27 remaining EU countries confirmed that the only kind of transition they will accept is a standstill in which Britain continues to apply all existing and new EU rules and laws. They are determined to exclude “cherry-picking” – Britain’s selective retention of EU policies that favor its interests.

EU countries are determined to exclude cherry-picking – Britain’s selective retention of policies that favor its interests.

According to Brussels, Britain, during the transition, must continue to make payments into the EU budget and respect the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, the free movement of workers and all EU international agreements. EU citizens arriving in Britain before the end of the transition period should retain lifetime rights to residence and social benefits. At the same time, Britain, as a non-member (“third country” in EU parlance), will have no say in EU decisions. It may be invited to send experts to certain technical bodies when this is deemed in the EU’s interest or when a specifically British issue is at stake, but they will have no voting rights.

The UK would be entitled to negotiate its own Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with countries around the world but would be unable to apply them while the transition lasts. The United States, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, South Korea, Singapore, India and others will not rush to conclude FTAs with Britain until its own future trade arrangements with the much larger EU market have been finalized.

During the transition, meanwhile, the UK would have to keep its market open to exports from countries having FTAs with the EU without any guarantee that they will offer reciprocal benefits to a non-EU member state. Turkish officials have long complained of a similar imbalance under their country’s own customs union with the EU. Lukewarm EU efforts to persuade international partners to offer equal treatment to Turkish exports have mostly fallen on deaf ears.

Under the kind of transition proposed by the EU, Britain would, effectively, remain inside the Union, but without voting rights. Rivals to the British prime minister, jostling to take her place, have decried this scenario as a form of servitude. In response, Theresa May has opposed EU demands, claiming, for example, that EU citizens arriving during the transition period should not enjoy the same rights as those present before Britain leaves. She says that these questions are open for negotiation but, with the clock ticking, the UK has little leverage.

Future relations

Beyond transition, the British prime minister has an ambitious but, in the present negotiating climate, unrealistic vision of her country’s future relations with the EU. She champions a “deep and special” long-term partnership, covering trade, security, defense, police and judicial cooperation, along with other areas of mutual interest. Its core would be an FTA, encompassing key sectors for the UK, including financial services. But EU leaders are wary of apparent British efforts to barter their security assets for trade concessions.

The EU has not yet taken a formal position on future relations with Britain. Germany and some of the Central European countries tend to be somewhat more accommodating than France, but all stand behind the EU’s official negotiator Michel Barnier. The 27 agree on the desirability of reducing the City of London’s dominance in eurozone financial affairs; that makes approval of a future deal giving British financial services free access to the EU market quite unlikely.

Instead, most member countries lean toward the notion of “equivalent” standards and practices as the basis for future trade in services. But this would probably cover no more than a quarter of services currently exported by the City to EU countries. It would provide little assurance to traders and investors, because recognition of equivalence could be revoked unilaterally at any time. British efforts to lock in “mutual recognition” of standards for services have met a frosty response.

EU governments refuse to grant special rights to London’s banking, insurance and clearing companies if Britain puts up barriers to European workers. From this perspective, the single market is indivisible: countries cannot pick and choose between free movement of goods, services, capital and labor.

Facts & figures

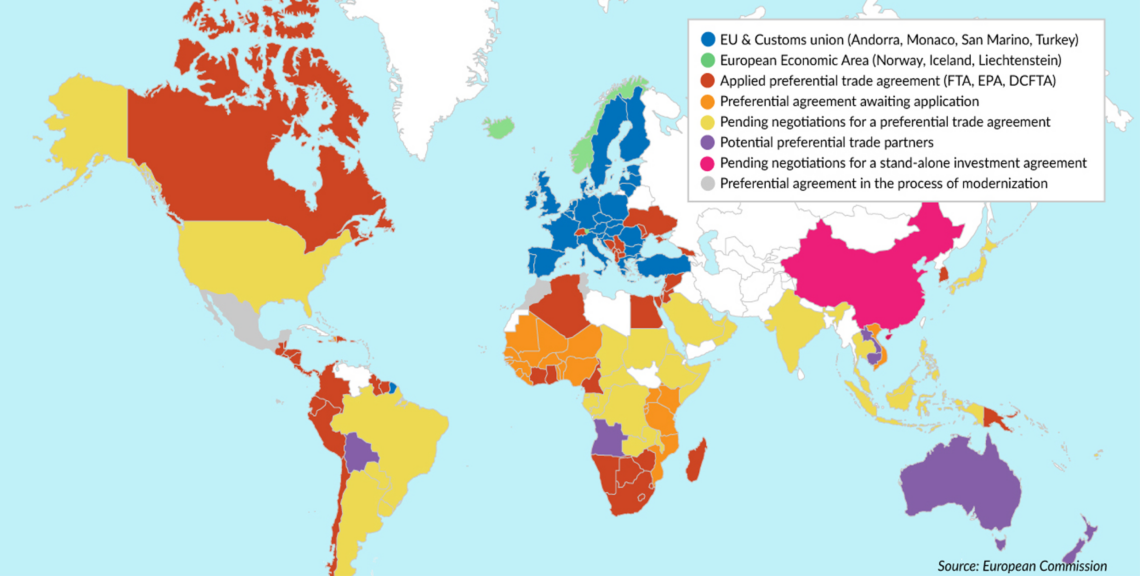

EU trade agreements

French President Emmanuel Macron recently said that the UK would be welcome to remain in the single market, with its reciprocal privileges. But this is anathema to Brexiters. They reject any arrangement whereby Britain would remain inside the single market, as a “rule taker,” like Norway. Besides, for many, “taking back control” of Britain’s external borders, to reduce immigration, is one of the main reasons for leaving the EU.

The 27 remaining member states would benefit from unobstructed trade in goods with Britain, especially given the complexity of cross-channel supply chains. Britain’s substantial military assets would add credibility to the EU’s embryonic security capacity. But Brussels looks suspiciously at a “bespoke” agreement cut to measure for Britain’s most competitive sectors.

Under these circumstances, the only remaining template, in the Brussels’ view, is an agreement along the lines of the Comprehensive Trade and Economic Agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada that took effect provisionally last year. CETA eliminates more than 90 percent of customs duties between the two sides, but has only limited provisions on agriculture and services. British negotiators might angle for a “Canada plus” agreement, but this would not cover the bulk of the services that the City of London now exports to the EU.

A shared belief that nothing is agreed until everything is agreed makes a hard Brexit even more likely.

Faced with this impasse, British politicians are considering the option of effectively staying inside the EU’s customs union to avoid cross-channel controls on goods and a hard border cutting through Ireland. But this will not work the way they seem to think it would, because checks on goods would be required once Britain is outside the single market and no longer covered by EU health and safety standards. It would also preclude separate British agreements on trade in goods with countries around the world. Now British officials are touting a partial customs union, with little prospect of success.

Hard Brexit

“Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed” is one of the few maxims shared by London and Brussels. This suggests that the preliminary divorce settlement – approved in principle last December, with ambiguous language masking important differences – could itself fall apart if the two sides fail to agree on transitional arrangements and a framework for future relations. This revives the specter of a “hard Brexit” with no preferential agreement in place and chaos in areas hitherto regulated by the EU, from aviation to nuclear safety and fisheries. Leaked government studies suggest that this could cost Britain the equivalent of 8 percent of gross domestic product in growth over the next 15 years.

In such a scenario, the Republic of Ireland would be particularly hard hit because of the volume of trade with the UK and the political implications of a new hard border with the North. Vague language about “regulatory alignment” to avoid such a barrier eased the way to December’s preliminary divorce settlement but could turn out to be a mirage.

Delaying Brexit?

With this dismal prospect, former Irish Prime Minister John Bruton is among those advocating a delay in Brexit to allow negotiations to continue for as long as needed to find a solution. This is possible under EU rules provided that all member states agree. Extending the negotiations would replace the awkward transitional arrangements currently under discussion. While the talks last, Britain would not become a “rule taker” or “vassal state” but instead would retain full membership rights pending agreement on the conditions for withdrawal. Clearly, some believe that British public opinion would wake up to the costs of Brexit during this “extra time” and that the UK might revoke its withdrawal notification. Key EU leaders have signaled that they would welcome such a change of heart.

Simply delaying Brexit is unthinkable in the present British political climate and may be unpalatable to the EU as well.

Still, this common-sense solution faces formidable obstacles. It would almost certainly bring down the government, which would probably be replaced by a more hardline, pro-Brexit cabinet. It would require the UK to participate in the 2019 European Parliament elections, despite the June 2016 referendum vote to leave the EU, and it would give Britain a say in the appointment of new EU leaders after the election. Such a scenario is unthinkable in the present British political climate and may be unpalatable to the EU as well. It might not receive the consent of all 27 remaining member states, any one of which could veto a Brexit delay for domestic political reasons.

Preventing Brexit

There is also more talk of a second referendum, giving the public a chance to think again once the outcome of the negotiations is known. Claims that “the people” have already given their verdict are spurious, because the public is only now beginning to grasp the complexity and likely economic impact of Brexit. Neither were seriously debated during the 2016 referendum campaign.

But in a political scene short of decisive leadership, a second referendum lacks convincing advocates. It is uncertain whether such a vote would include a clear option to remain, and the timing is crucial. The government is unlikely to propose a referendum unless forced by a vote of the House of Commons. Even then, the result of a second referendum would be unpredictable. A narrow majority either way would fail to convince half the country and create further uncertainty. There might even be calls for a third referendum.

The most likely way for Britain to avoid leaving at midnight on March 29/30, 2019 is for the House of Commons to vote down a government motion approving the final settlement on exit, transition and the general framework for future UK-EU relations. In principle, this vote will take place in October, but it could be pushed back to December or even January. If parliament rejects an exit deal, this would be followed by a government defeat on a confidence motion.

The agenda of some leading Brexiters is for Britain to become a sort of low-tax offshore center outside the EU’s regulatory orbit.

The situation could then unfold in several distinct ways. There might be renewed calls for a second referendum, still feasible before Brexit day if the parliamentary vote takes place in October. The government could fall and there would be a general election, or a different Conservative leader might form a government, or the leader of the Opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, might head a minority cabinet. A new government might play for time and request a prolongation of the negotiations. It might thereby succeed in delaying Brexit, despite the formidable obstacles discussed above.

However, any new euroskeptic prime minister might simply let the negotiations lapse, leading to a hard Brexit, with all the related disruption. This would fit into the not-so-secret agenda of some leading Brexiters for Britain to leave the EU’s regulatory orbit and become a sort of low-tax offshore center, offering sweetheart deals to attract investors. The European Commission has warned that this would lead to severe retaliatory measures.

On balance, it is unlikely that enough Conservative MPs would vote against a withdrawal agreement for it to be defeated in parliament. They could then be accused of disloyalty and of ushering in a Labour government led by Mr. Corbyn. This adds to uncertainty as the March 2019 withdrawal date draws near.

Smart money

The history of European integration is strewn with upsets that belied the best-argued predictions. Still, investment decisions will not wait. The smart money is on British withdrawal in March next year – with or without an agreement to smooth the way.