Japan opts for another round of fiscal stimulus

Japan is looking for ways to reduce its public debt, currently worth more than 200 percent of its GDP. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has managed to raise taxes, but the government’s budget for this year still relies on social programs to convince consumers to spend.

In a nutshell

- Japanese consumers are still reluctant to spend

- The government has used fiscal stimuli to reverse this trend

- Demographic constraints put a damper on demand

Japan, the world’s third-largest economy, starts the new decade using the same macroeconomic remedies it has been applying since the launch of “Abenomics” under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe some seven years ago. Some supporters of the government insist, however, that the country has reached a turning point and that the strategy will bear fruit in the near future.

Is this optimism well-placed? As always in such a complex country as Japan, the answer remains ambiguous. Japan has several hidden strengths that are all too often overlooked.

Abe’s optimism gambit

When Shinzo Abe started his second term at the end of 2012, he was unusually bold in claiming that his “three arrows” policy would extract Japan from the economic stagnation in which the country had been mired since the economic bubble burst at the end of 1989. This daring claim was made in the face of a clearly incompetent opposition and with the support of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party that had become tired of the “revolving door of prime ministers.”

Some of Prime Minister Abe’s optimism was aimed at shaking a rapidly aging society out of its skepticism, reluctance and even despair. Part of this enthusiasm has since disappeared or turned out to be delusional. Japanese society is like a supertanker: it requires a lot of time and effort to change course.

The 1990s and the first 10 years of this century were lost decades.

From the start, it was clear that the ambitious goals the prime minister had set would not be reached easily. Although the LDP dominates national government, it cannot do whatever it wants – it must take into account entrenched institutional interests.

Once the speculative bubble that had emerged in the real estate sector and in the financial markets had burst, Japan’s economy did not return to the high growth rates of the 1970s and 1980s. Though the Japanese economy did not do as badly in the 1990s and 2000s as the international media claimed, the country’s macroeconomic woes were drastic by the standards that had been set in the postwar period. There is no doubt that the 1990s and the first 10 years of this century were lost decades.

Facts & figures

Demographic constraint

One of the major challenges for the government and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) was to prevent Japan from descending into deflation. Since the bubble burst, prices have hardly moved and the inflation rate has mostly remained well below the two percent target set by the central bank.

Several factors worked to keep inflation low. The first was the yen’s strength outside the country. This came with very little elasticity from customers domestically – Japanese consumers remained tightfisted. In the absence of rising prices, they could see no reason to purchase big-ticket items. Government incentives to loosen consumers’ purse strings had little effect. A tight labor market and general anxiety about the prospects for the Japanese economy motivated people to save rather than spend.

Facts & figures

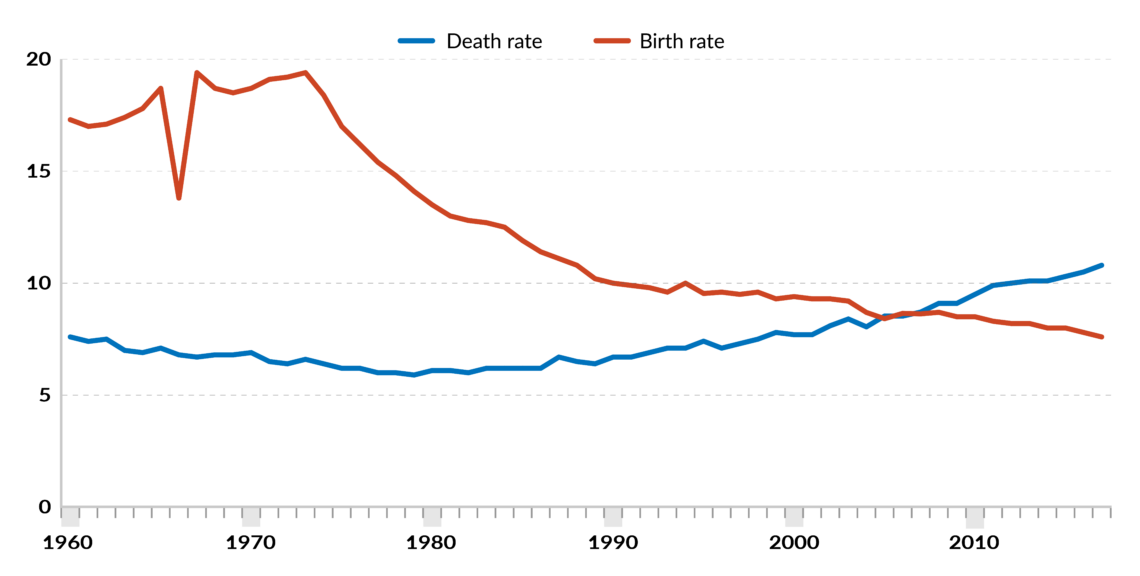

The most important structural constraint on the Japanese economy is demographics. Japan’s population is rapidly aging and shrinking, which reduces domestic demand. The negative demographic trend is hurting virtually the entire Japanese economy, except for the healthcare and elderly care sectors. Fewer children are born, fewer people enter the job market and get married, fewer households are established, and so on. The vicious circle depresses demand.

Bearing in mind its demography and level of socioeconomic development, we can see why Japan’s monetary policies – like other industrialized societies in the West – are now reaching their limits.

Consumption tax hike

While Japan can maintain higher levels of public debt than other highly industrialized countries, Tokyo is aware that the current trend of ever-higher indebtedness is not sustainable. Even the patience and patriotism of the dutiful Japanese citizens have their limits.

On one hand, Japan can, for the time being, still count on its own citizens to buy its debt – a remarkable difference compared to other major economies. Over 95 percent of Japan’s public debt is held by the Japanese. On the other hand, as the population ages rapidly, more and more old people will be forced to draw on their savings.

As part of the strategy to deal with the ballooning debt, Prime Minister Abe has doubled the consumption tax.

As part of the government’s strategy to come to grips with the ballooning public debt, Prime Minister Abe has doubled the consumption tax, from five percent to 10 percent. Compared to other industrialized countries, particularly in Europe, this is still a low level of indirect taxation. For Japan, however, the rise was significant.

For all too long, governments had shied away from hiking the consumption tax, since doing so would have been extremely unpopular. After some hesitation, Prime Minister Abe went ahead with the move – and did so without substantial damage to his own approval ratings. However, many economists have criticized the decision, maintaining that raising indirect taxes was the wrong step at a time when consumers were already reluctant to spend.

Record budgets

Prime Minister Abe is fully aware of the deflationary danger that comes with the steep rise in the consumption tax. This is clear in the 2020 fiscal budget that his government recently presented to the Diet. The budget will enter into force on April 1 and envisions record spending of 102.66 trillion yen (about $940 billion), marking the second year in a row that the budget has crossed 100 trillion yen. Finance Minister Taro Aso, a close ally of Prime Minister Abe, said that the budget “is aimed at achieving both economic recovery and fiscal consolidation by improving social security through the use of increased revenue from the consumption tax.”

As it stands, it is unlikely that the government will reach the ambitious goal set by Finance Minister Aso. First, it is unclear how the higher consumption tax will affect consumer behavior in the long run. Second, while it makes sense to use the increased tax revenue for social policy measures, it is questionable whether the government will exercise fiscal discipline when it comes to other budget items.

Furthermore, the government will have to spend more on defense. The United States is pressing Japan to increase the amount it pays to offset the costs of American bases there, and the country’s defense needs have increased due to geopolitical tensions in the region. Circumstances indicate that defense outlays will continue to rise substantially in the years to come.

Growing debt

Bearing all this in mind, it is highly unlikely that Japan’s enormous public debt will be contained, never mind reduced, in the years to come. In fact, priorities set out in the budget point to an increase in public debt. With a general election potentially looming in the not too distant future, fiscal discipline is even less likely.

Taking all this into account, we can come to several conclusions. First, the government will not be able to significantly increase revenue. It will probably not collect much more from the consumption tax, and another rise has been ruled out. Consumer spending will not increase substantially, so neither will revenue from the consumption tax – all the more so considering the remote prospects for a rise in inflation.

The options for substantial cuts in expenditure are very limited.

The draft budget shows that the options for substantial cuts in expenditure are very limited. This is most notably the case for the fiscal burden of the social security expenditure. At the beginning of 2020, the Bank of Japan reiterated that it is continuing its monetary policy and it sees no need to change its quantitative easing measures for now: it will continue to purchase assets and, unlike in some other central banks in the West, it will not reverse course on its ultra-low interest rates.

The question that remains is whether the BOJ’s optimism about a substantial recovery in private investment and private consumption will prove well-founded. It is true that pressure from the outside, most notably from the U.S. on Japanese exporters, has receded a bit. However, experience shows that this state of affairs could change rapidly.

Hope for growth in the Japanese economy can only come from the fiscal stimuli filtering through to ordinary citizens. There is room for cautious optimism here. Salaries are rising, while more Japanese are working in formal, steady jobs as opposed to temporary work. In fact, substantial shortages in the job market loom. Efforts to contract labor from abroad to make up for domestic shortfalls has not had the success the government had hoped for. Fiscal stimuli have a wider scope to work, since low interest rates and the Japanese public’s reliability in buying government bonds mean there is not urgent pressure to service the debt.

For now, the question of how long Japan can remain a “special case” and continue to operate with a debt burden of more than 200 percent of gross domestic product will remain unanswered. Looking at the current budget, a change of course does not look possible anytime soon.