Liberia and Sierra Leone: post-conflict, focused on growth

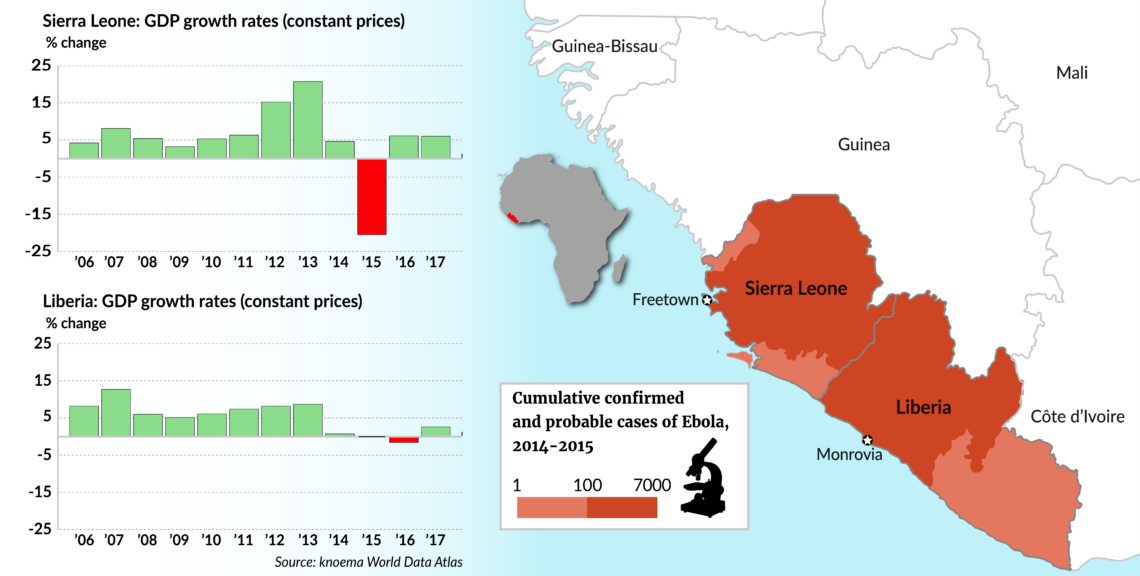

Liberia and Sierra Leone went through painstaking a post-conflict restoration process after civil wars that ravaged them in the last decade of the 20th century. In 2018, newly elected leaders in Freetown and Monrovia face the task of restoring growth in the economies badly hindered by 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic and low commodity prices.

In a nutshell

- New leaders in resource-rich Liberia and Sierra Leone are focusing their energies on spurring economic growth

- Both governments have to reckon with depressed commodity prices and declining remittances

- Their selling points are internal stability and improving governance that help in attracting investors

West African nations Liberia and Sierra Leone can be considered successful cases of post-civil war political and security reconstruction. Their underdeveloped and underperforming economies, however, are clouding both countries’ prospects. In 2014-2016, the worst-ever outbreak of Ebola and a commodities slump depressed their growth, but new leaders are taking over the governments in Monrovia and Freetown on the promise to revive the economies.

In Liberia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was succeeded by George Weah after elections that largely met international standards. In Sierra Leone, two strong candidates are competing in the presidential runoff.

Liberia’s post-conflict transition

Liberia is one of the few African countries that were not colonized by Europeans. The continent’s oldest republic was funded in 1847 by freed slaves from the United States and the Caribbean. Today, it has a population of some 4.7 million. Its development history is rocky, periods of relative stability and prosperity (in the 1950s, Liberia was among the world’s fastest-growing economies), alternated with political turmoil and economic collapse. Between 1989 and 2003, the country was ravaged by a civil war that claimed a quarter of a million lives, displaced half of the population and demolished its economy. In 2005, after the first phase of an internationally-assisted post-conflict transition and reconstruction process, Ms. Sirleaf won the presidency, becoming the first woman ever elected head of an African state.

The country has been stable and held three consecutive national elections between 2005 and 2017.

Although her tasks were Herculean, she laid solid foundations for the country’s progress. As a former World Bank and United Nations official and one of Africa’s most respected women, President Sirleaf made good use of her excellent connections among donors, in business circles and in the country’s diaspora. The international community in general and the United States, in particular, committed to the reconstruction of Liberia, while its leader enjoyed strong support at home. She personified the kind of boundless energy and potential that often characterize post-conflict societies.

Reelected in 2011 to a second term, President Sirleaf has left the office with a strong record. (Liberia’s constitution limits presidents to two terms.) A Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2011 (with two other female activists for women’s rights), she was also awarded the Mo Ibrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership. In the last 10 years, including in 2015 and 2016, this coveted prize was not awarded six times for lack of suitable candidates. Ending the trend, Ms. Sirleaf became the 2017/2018 Mo Ibrahim recipient for “laying the foundations on which Liberia can now build.”

Claiming that Liberia’s postwar democratic transition is completed would be an overstatement, but the country has been stable and held three consecutive national elections between 2005 and 2017. It has a robust multiparty political system today: as many as 16 different parties participated in the last national elections. The former president was a member of the Liberian Unity Party, but the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC) dominates both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Liberia’s state apparatus, reformed under the umbrella of a United Nations’ peace-keeping force (its mission ends as of March 30, 2018), has demonstrated its ability to securely conduct national elections.

Economic transition

President Sirleaf’s government, among other achievements, put the country’s finances on an even keel. In 2010, Liberia acquired a $4.6 billion debt relief from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The deal reduced the country’s external debt by more than 90 percent, to some 15 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). From 2006 and 2013, Liberia’s economic growth averaged an impressive 8 percent. It was attributed to the lifting of the embargoes on the country’s timber and diamond exports, a streamlined regulatory regimen and generally improved business environment, which attracted foreign investment into the mining sector.

In 2014, though, this growth was halted by the Ebola epidemic. It had both economic and political consequences, exposing Monrovia’s limitations in managing the crisis and undermining the government’s popularity. But even in the face of the Ebola-related failures and Liberia’s frailty as a post-conflict society, the country’s political and security environment has remained unaltered.

Challenges of tomorrow

The winner of the 2017 presidential elections and Ms. Sirleaf’s successor is George Weah. A former soccer star (hailed as one of the greatest African players of all time), he founded the Congress for Democratic Change party in 2005, shortly after ending his career in sports. With no previous political experience, he emphasized his outsider status and attacked the entrenched political establishment. Defeated by Ms. Sirleaf in the 2005 presidential runoff, he ran again in 2011, this time for the post of vice president, and lost again.

This time around, Mr. Weah managed to stay ahead of the Unity Party candidate, Vice President Joseph Boakai, in the first round and won the runoff with more than 60 percent of the vote. His popularity among Liberia’s urban and disenfranchised youth was critical for this outcome, but support from President Sirleaf (who had crossed party lines to back Mr. Weah in the campaign), played a big role as well.

Remittances from the Liberian diaspora account for more than 25 percent of GDP.

The new president has advocated further opening of the Liberian economy and retooling it to foster the growth of the middle class. He also announced that he would revoke the law under which only people of color can become Liberian citizens and own property.

The challenges that the government faces are above all economic and social. According to the African Economic Outlook, the country’s poverty rate is 54 percent. Liberia ranks 177th out of 188 on the UN Human Development Index, and the proportion of workers in vulnerable employment is at a whopping 76.6 percent, within an economic context of low productivity. Corruption remains pervasive in the public sector and foreign aid accounts for more than half of its gross national income. Remittances from the Liberian diaspora account for more than 25 percent of GDP.

Improving this economic picture will not be easy for the new government, as it faces three unfavorable trends: prices of the country’s main export commodities, rubber and iron ore, are expected to remain low, while those for agricultural products are projected to increase (Liberia imports 80 percent of its foodstuffs). And aid flows to the country will probably decrease.

To tackle these problems, President Weah formed a cabinet composed mostly of men from his CDC party. Nathaniel McGill, the party’s chair and the right-hand man of the leader, has been appointed minister of state and cabinet chief. The nomination of Samuel Tweah as minister of finance and development raised eyebrows in the financial community, and spurred doubts regarding the consistency of his “pro-poor agenda.” President Weah also relies on the implicit support of former President Sirleaf.

Sierra Leone: political parties’ game

In Sierra Leone, like in Liberia, the sitting president is constitutionally ineligible to run again for a third five-year term. After 10 years in office, President Ernest Bai Koroma is leaving the field to three main contestants. There was no announced winner ahead of the presidential elections on March 7, 2018, or the runoff on March 27, which was a good sign of democracy taking root in a country also recovering from one of Africa’s most violent conflicts. A “province of freedom” created by the British Abolitionist Society back in 1787 for the repatriation of slaves, Sierra Leone became independent in 1961. Until 2002, it made news because of military coups, tumultuous power transitions and, finally, a long and brutal civil war (1991-2002).

In contrast to many African countries, politics in Sierra Leone revolve around political parties rather than leadership figures. Since independence, two parties have dominated the landscape: The All People’s Congress (APC) and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP). Party affiliations are largely determined by regional and ethnic factors.

The APC’s support base consists mostly of members of the Temne and Limba ethnic groups, concentrated in the north of the country, while the SLPP support basis is in the south, home of the Mende ethnic group.

Old versus new

The SLPP governed Sierra Leone in two periods: from independence until 1967, and between 1996 until 2007. The ruling APC was the country’s only legal party between 1978 and 1991. Despite the central role of its political parties, Sierra Leone is formally a presidential regime. The 2018 elections turned into a contest between three strong candidates.

None of the three candidates secured the 55 percent of the vote needed for a first-round victory. Julius Maada Bio, the retired brigadier general in the Sierra Leone military who lost the 2012 presidential race, is again the flag bearer for the SLPP. He won the first round of the balloting with 43.3 percent of the vote, a razor-thin margin over the ACP candidate, who secured 42.7 percent.

Some agriculture-led growth returned in the rural areas, but Sierra Leone’s urban areas remain depressed.

Mr. Bio, who was involved in two military coups during the 1990s, cuts a polarizing figure. The SLPP candidate, though, has come up with a coherent program for the country. It is focused on revenue mobilization, public expenditure and debt management and diversification of the nation’s economy.

On the other side, Samura Kamara is the candidate of President Koroma’s APC and an experienced public servant. A former foreign affairs minister, finance and development minister, and the governor of the Bank of Sierra Leone, Mr. Kamara stands for continuity in the country’s policies. Also, he has good contacts in Beijing. Chinese investment in Sierra Leone increased during the APC’s rule.

One of the surprising outcomes of the first round was the poor showing of Kandeh Yumkella. A former United Nations official, he is a self-described liberal and the flag bearer of the newcomer National Grand Coalition, which enjoys support in the country’s north and among the youth. Unable to secure a leading candidate slot within the SLPP, Mr. Yumkella has decided to run as a “third-way” candidate. His “New Force of Hope and a Coalition of Progressives” platform ostensibly remains above the tribal and regional considerations.

Breakaway parties are nothing new in Africa, especially among the opposition forces. These initiatives are often led by younger, charismatic activists whose ambitions are held back within the established political organizations. Limited support in the first round of the election for Mr. Yumkella may be indicative, however, of continued strength of the two main parties.

Scenarios

Like in Liberia, economic growth in Sierra Leone surged after the civil war, boosted by peace, stability and the exploration of newly found iron ore deposits. In 2013, according to the World Bank, the country’s economy grew at an estimated rate of 21 percent. The outbreak of Ebola and weakening of commodity prices depressed this growth in 2014-2015. Currency depreciation followed. Recently, some agriculture-led growth returned in the rural areas, but Sierra Leone’s urban areas remain depressed, with youth unemployment rates high. About 60 percent of the country’s population is under 25.

Both Liberia and Sierra Leone are nearly through their post-conflict reconstruction. The two countries’ political and security environments have decidedly improved over the past decade. The main threat to their stability comes from underdeveloped economies.

In Liberia, the 2017 elections reflected the political potential of the younger generations. In the case of Sierra Leone, despite the emergence of a “third-way” candidate, polarization and regionalism proved their resilience.

The political and security improvements made in both countries during the post-conflict phase are sustainable. Some negative trends from the past do persist (in Liberia, for example, Vice President Jewel Taylor is the ex-wife of former warlord Charles Taylor), but the worst-case scenarios of renewed conflict, ethnic violence or “warlordism” are unlikely to materialize in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

If, on the other hand, fast economic development is not reignited, social tensions may intensify and politics could again spill out into the streets. Within this context, warlords and Islamic groups may resurface in both countries’ political space.

Under a best-case scenario, the new leaders will capitalize on the political and security gains of the recent years and bring improvements on the economic front. Although low commodities prices and declining levels of aid represent a challenge in the near term, both countries can restore high growth rates on the basis of their mining resources, agricultural potential, and demographic strength.