Looking for a way out in Libya

The recent outbreak of fighting in the capital of Libya shows who are the real masters of the country – the militias. The international community’s focus on reconciling the feuding governments ignores that they have been captured by local warlords.

In a nutshell

- Local militias have become a “cartel” controlling Libya’s administration and economy

- Foreign peace efforts have taken a top-down approach through empty state institutions

- Until this strategy changes, attempts to use elections to unify the country will fail

At the end of August, Tripoli was shaken by another round of street fighting. Militias fought pitched battles in the southern suburbs, using tanks, heavy artillery and rockets. At least 61 people were killed and more than 150 injured. The authorities put all hospitals and private clinics on alert to deal with the casualties. The guards at Ain Zara prison in southeast Tripoli fled for their lives, leading to a breakout of 400 prisoners. The Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA), backed by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), declared a state of emergency – which was ignored by all sides.

This outbreak can be viewed as part of the maneuvering ahead of parliamentary and presidential elections planned for December – a step agreed between Libya’s two main political factions to unite the country and end a seven-year civil war. Many local groups are not eager to give up their weapons and influence, and will go to any lengths to block or delay the electoral process.

Militia rule

But the fighting in Tripoli is also a turf battle, a routine fight for control in a city where every militia has its own interests – distinct from and often more powerful than those of the central authorities. It is important to remember that all parties in the latest fighting – the Tarhouna-based Kaniyat (Seventh Brigade) and a coalition of other militias in the southern part of the city – are nominally aligned with the Tripoli government. That has not prevented repeated clashes. In 2017, for example, street battles erupted in March, May and October.

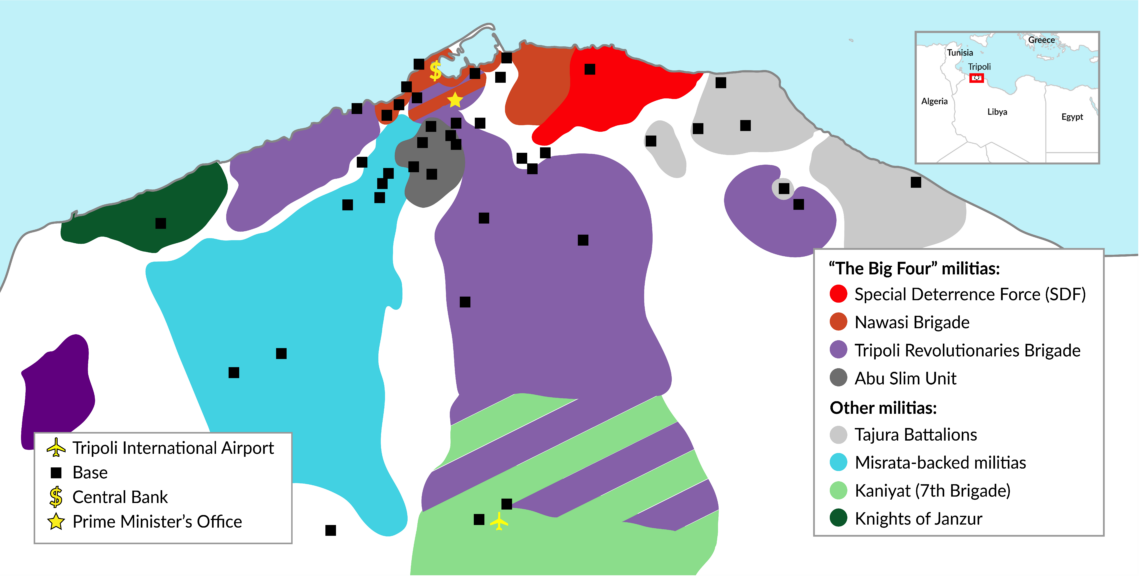

Effective control of the capital is in the hands of four armed groups: the Special Deterrence Force (SDF), led by Abd al-Rauf Kara; the Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade, led by Haitham al-Tajouri; the Abu Slim unit of the Central Security Apparatus, led by Abdelghani al-Kikli; and the Nawasi Brigade, led by the Qaddur clan. At this point, according to a detailed analysis by the German security expert Wolfram Lacher, these four militias have evolved into a “cartel” that has captured economic assets and central institutions, eclipsing the power of the GNA and even holding it hostage.

The situation is very different from 2012-2014, when Tripoli’s dozens of militias were on the government payroll.

The current situation is very different from 2012-2014, when Tripoli’s dozens of local militias were mostly on the payroll of the Defense and Interior Ministries. But the outbreak of the second civil war in 2014 blocked the flow of government money, starving the militias of cash and forcing them to look for alternative sources of funds – at first through smuggling and kidnapping, then by taxing local businesses, and finally by tightening their control over banks and state institutions.

By gaining direct access to the public revenue stream (especially the ability to purchase dollars from the central bank at below-market rates), the more successful militias expanded dramatically, absorbing or marginalizing smaller groups.

Regional divisions

Seven years after the revolution that toppled Moammar Qaddafi, stability in Libya remains a chimera. The country is still split into two parts, with one government in Tripolitania and another in Cyrenaica. The GNA, led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj, enjoys the official support of the international community through UNSMIL and its new special envoy, Ghassan Salame from Lebanon.

Created by the Skhirat Agreement of December 2015, the GNA arrived in Tripoli by boat. It never found support on the ground. Weak and unable to win the allegiance of ordinary Libyans, it was forced to turn to Tripoli’s stronger militias for protection. It soon became utterly dependent on them.

Facts & figures

Armed groups in Tripoli, June 2018

In the eastern part of the country, Tobruk became the base for the House of Representatives (HoR), formed from the secular parties that won the 2014 elections and then were forced to leave the capital during the second civil war. Aguila Saleh Issa is the HoR’s nominal president, but the strong man in Tobruk is Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, a general who lived for many years in exile in the United States after falling into disfavor under the Qaddafi regime. After the revolution of 2011, he emerged as the commander of the Libyan National Army.

To the south is Fezzan, historically a no man’s land, whose tribes are controlled neither by the GNA nor the HoR.

These regional divisions have persisted and even deepened under UNSMIL’s international mandate, in part because they are being encouraged by foreign powers. From the second civil war in 2014, Tripolitania has been supported by Qatar and Turkey, while Cyrenaica is sponsored by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Russia. This steady outside interference has distorted the normal process of “natural selection” in Libyan politics, preventing the emergence of a clear winner. Instead, the country has become a chessboard for a proxy war between Qatar and the UAE, while being exploited for its immense oil and gas resources.

Political vacuum

If Libya’s internal divisions in 2014 were still mainly of a regional nature, inherited from the period of Italian colonization and the reign of King Idris (1951-1969), in the years since they have multiplied and worsened, as infighting and lawlessness have unraveled the social fabric of local communities.

The country’s west, east and south have become increasingly subdivided, as different militia groups compete for predominance. The law of the jungle prevails. This fragmentation and the complete disintegration of the Libyan state makes it a moot point whether elections are held or not. Few seem interested in the real issue, which is how to disarm and reintegrate the dense patchwork of militias that is really running the country. They are the main obstacle to political stability and, as a last step, to democratic government in Libya.

One reason the international community had difficulty coming to grips with the complex situation in Libya is that it did not grasp the hollowness of the Qaddafi regime, which was built on a social and political vacuum. Libyans had no opportunity to become acquainted with democracy or self-government. And even when they got that chance after the 2011 revolution, they lacked the necessary institutions and know-how.

Outsiders had difficulty coming to grips with Libya because they did not grasp the hollowness of the Qaddafi regime.

Those initial shortcomings and mistakes created the conditions we see today. Nothing really works in Libya – neither the economy nor the political environment nor the security sphere. International organizations continue to take a superficial, top-down approach to the country, engaging in high-level meetings with politicians who often have little domestic support or credibility. Like pied pipers, they never keep their promises, while in the streets disappointment and anger grows.

Any possibility of bottom-up political mobilization has been hindered by this lack of experience, but above all it has been stifled by the country’s hundreds of local militias, which exercise the real monopoly of force. These groups act with impunity, since they have supplanted and replaced all official security organizations.

Heavily armed, they use checkpoints to monitor every street. They control local politics and the economy, blackmailing or attacking high-level officials and journalists, while exacting payments from local businesses and public institutions. On the central government level, they have been able to extort funds from the central bank and the National Oil Corporation by seizing or threatening oil fields and vital installations.

Playing with fire

In May 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron hosted a conference in Paris attended by four key figures from the Tripoli and Tobruk governments – Prime Minister al-Sarraj of the GNA; the newly appointed head of the GNA’s Council of State, Khaled al-Mishri (also affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood); HoR President Aguila Saleh Issa; and Khalifa Haftar, the LNA commander. The meeting set a date of December 10, 2018 for presidential and parliamentary elections, to be preceded in mid-September by approval of the necessary constitutional amendments and an electoral law.

Some analysts considered the Paris Agreement – which was endorsed but not actually signed by the various parties – as decidedly premature. Judging from recent experience, it was likely to do more harm than good to Libya’s already fragile political equilibrium. The previous Libya summit hosted by Mr. Macron in July 2017 yielded a heavily publicized declaration calling for a ceasefire, the creation of a national army, and preparations for a nationwide vote that Mr. al-Sarraj wanted to be held in March 2018. In the end, it led to absolutely nothing.

In a country completely controlled by militias, holding elections too soon is playing with fire – especially when the leaders of these armed groups are not invited to the negotiating table. In the absence of a constitutional framework, every single spark can start a conflagration engulfing the transitional government – as we have seen with the confrontations over the oil industry and control of Tripoli in the past two months.

Meanwhile, lawmakers in the HoR – which would have to leave its secure base in Cyrenaica and move back to Tripoli under a unity government – seem to be stalling the electoral process. Their president, Aquila Saleh Issa, had the task of getting the legislature to approve a package of laws that would allow a referendum on the draft constitution (approved by the Libyan Constitutional Assembly in July 2017) and the presidential and parliamentary elections to take place. Under pressure from the international community, Mr. Saleh promised and then reneged on succeeding deadlines for passing the measures.

On August 27, the HoR could not muster a quorum to vote on the measures, prompting its president to warn that he may be forced to bypass legislators by using Decree No. 5 of 2014 to hold elections for a temporary president.

Electoral gamble

Mr. Saleh missed a last opportunity to get the legislation passed at the HoR’s September 3 session. After this failure, there is a chance he might go through with the threat to invoke Decree No. 5. That would be a mistake. He would only undermine the legitimacy of the vote and open the way for a contested election result. Without constitutional amendments, there is no legal basis for a national vote (the 2011 constitution does not provide one). The only way to remedy this situation is to hold a national referendum on the draft constitution by September 16. In Libya’s current situation, organizing such a vote in less than two weeks is virtually impossible.

A failed or fraudulent election could plunge Libya into a third civil war, which the country might not survive.

On top of that, the deeper threat of the militias remains. These groups are fluid in their alliances, ruthless in their pursuit of power, and armed with more than 20 million light and heavy weapons – a staggering total for a nation of only 6 million. Unless their influence is curbed, holding elections in this polarized setting – with or without a valid constitution – is an enormous gamble. What President Macron and many other international leaders fail to appreciate is that a failed or fraudulent election could plunge Libya into a third civil war. In its present economic condition, the country might not survive another conflagration.

History teaches us that building democracy is a long, painful march toward a distant goal. Western democracies know this very well. That is why even if the Libyan referendum succeeds, the scenario for elections is not positive. The country lacks the political maturity for that. Elections are the culmination of a democracy, not the beginning.

The solution is not a Sarraj or a Haftar government; neither has been recognized by the population or enjoys an electoral mandate. Far from being saviors, these leaders have contributed to the polarization we see today and the chaos that seems likely in the short and medium term.