Could Murban crude become a new oil benchmark?

The trade launch of the United Arab Emirates’ flagship oil, Murban crude, marks yet another step toward privatization and competitiveness for the Emirati energy sector. It could become a new benchmark in the Middle East – and possibly beyond.

In a nutshell

- Abu Dhabi has launched a new crude futures contract

- The UAE’s flagship oil Murban could become a new benchmark

- Emirati oil policy is betting on competitiveness

In March 2021, a new crude futures contract was launched in Abu Dhabi: Murban futures, traded on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). The Abu Dhabi National Oil Company’s (ADNOC’s) flagship crude oil Murban accounts for nearly 2 million barrels a day, or half the United Arab Emirates’ production. Its delivery point is in the port city of Fujairah, whose importance as a regional storage and export hub is likely to grow.

The launch was a long time in coming and keenly awaited. Back in November 2019, Abu Dhabi’s Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC) – the highest governing body of the oil and gas sector – announced that the pricing of Murban would change. Rather than being mostly the output of bilateral bids, offers and agreements, for example between ADNOC and a particular refinery in another country, pricing will now move to an international exchange on a market-driven, forward-looking basis, open to all parties, and using a new futures contract as the price marker.

Facts & figures

Oil futures contract

In this type of agreement, one party agrees to buy a type of oil at a predetermined price in the future. If the market price is above this figure by that time, the purchasing party will have earned a profit by securing a lower price.

As part of the new arrangements, the SPC also authorized ADNOC to remove existing destination restrictions on Murban crude sales. Such a modern setup seems aligned with the broader reorientation of Abu Dhabi’s oil policy over the last few years, whereby greater emphasis has been placed on market mechanism, privatization and competition. Awarding oil blocks by competitive licensing rounds is one example. Selling some of ADNOC’s downstream assets is another. In this respect, long before Murban futures, Abu Dhabi had already been positioning itself differently than its neighbors and OPEC fellows.

Basic economics suggests that Murban’s odds are good.

This is not the first nor will it be the last time that someone, somewhere in the world attempts to establish a new crude oil benchmark. Many past efforts have failed – for lack of market interest or transparent infrastructure, or just because there was no need for another crude price benchmark.

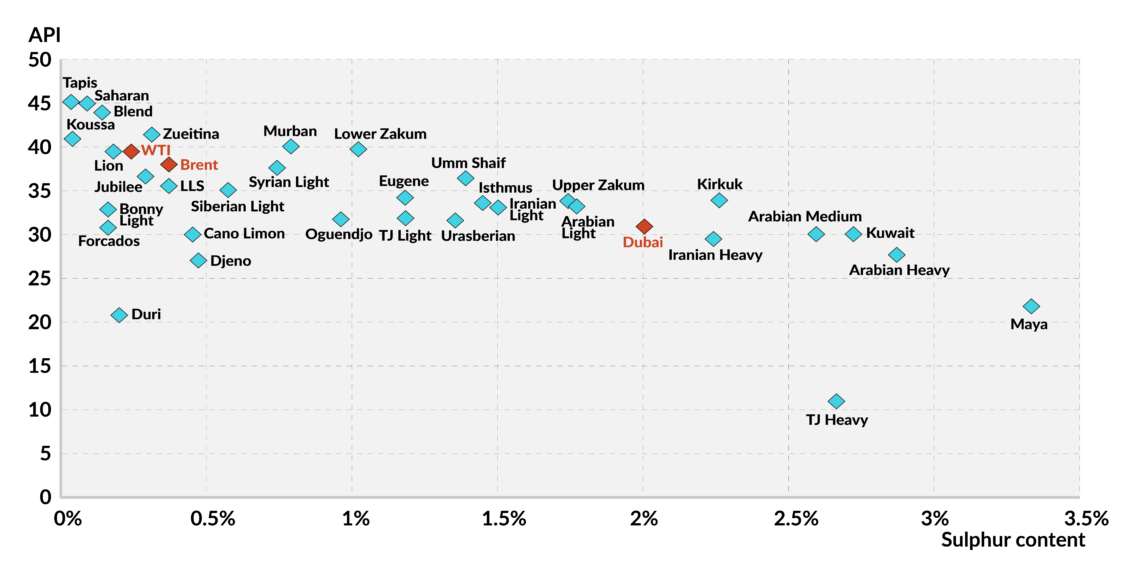

Why should it be different this time? And why does the world need another crude benchmark? Although we talk about a global market for oil, not all oil is the same. Density and sulfur content vary. High density makes the oil heavy, and inversely low density makes it light. So-called sweet oil has a low sulfur content, and sour oil a high one. Based on this combination, the price of any given crude oil type (or its “grade”) is set using the price of a specific benchmark (also known as “marker crude”) as the reference price.

The main such references are Brent, from the North Sea, and West Texas Intermediate (WTI). Both are light and sweet. WTI is mostly destined for U.S. domestic consumption, while Brent is produced offshore and has become the most widely used international marker. Crude oil benchmarks from Dubai and Oman (light and sour) are also used, primarily for crude oil from Gulf countries and even Russia. Murban oil, meanwhile, is light and sweet.

Facts & figures

Basic economics suggests that Murban’s odds are good. In the Middle East, oil is typically sold under bilateral agreements between producer and buyer. Many countries, for example Saudi Arabia, have strict destination control, prohibiting buyers from reselling purchased oil. By switching to a market-based mechanism and removing destination restrictions, more players will be involved and the oil will become accessible to more buyers. The more players involved, the more liquid and transparent a market is. Efficiency increases, lowering search and transaction costs for everyone. Of course, one could argue that the oil market is already liquid, and that it will take time for additional benefits to materialize. But for market participants, there is no such thing as too much depth, liquidity and transparency.

Neither Dubai nor Oman can compete with Abu Dhabi’s oil production.

The second question is whether Murban will achieve the same prominence as these established regional markers and become an alternative Middle East benchmark, or even a global reference.

Scenarios

Murban is likely to survive the main existing benchmarks primarily because of the larger volumes involved – current and future. It could easily become the benchmark of choice for Middle Eastern crude. Neither Dubai nor Oman can compete with Abu Dhabi’s oil production. Oman’s total output is less than half of ADNOC’s Murban.

Of course, the success of a new benchmark is never guaranteed. The outcome will still depend on buyers’ appetite. Russia has tried to turn Urals into an international benchmark, for example, with limited success and little international interest. But Murban stands a much better chance. The groundwork has been laid well and now it is largely politics, not economics, that could get in the way of its adoption by other major Middle East producers.