Nordic disunion

One might expect the Nordic countries, with their strong democracies and economies, to be full-throated backers of the European project. But the differences between them have led to strained relations that are undermining their relationships with Brussels.

In a nutshell

- Cooperation between Scandinavian countries is limited

- Sweden’s approach to the migrant crisis has deepened divisions

- This has led to a focus on security issues

- Crucial European Union matters have taken a back seat

As the mandate for “more Europe” wears thin in the continent’s south and east, a key question for the European Commission is whether it can still count on support from countries in the Nordic region. At first glance, these would seem the ideal supporters – strong, technologically advanced economies with stable, healthy democracies free of corruption and governments always ready to shoulder international commitments.

But if it looks too good to be true, it probably is. For all their outward similarities, the Nordic countries are in many ways very different. The migration crisis has put these differences on full display in political conflicts that undermine the region’s cohesion and relations with the European Union.

Happy talk

There is no shortage of happy talk about common Nordic interests. In some cases of regional cross-border cooperation, like in the Arctic region, it works rather well. In the field of intergovernmental cooperation, however, the lack of commonality shows.

The Nordic Council, for example, consumes resources and employs bureaucrats, but nobody seems to know precisely what it does. Plans have been floated for a Nordic defense union and a Nordic economic union, but neither to much avail. Recent fears of a collapse of the euro served to reignite discussion of a common Nordic currency, again to little effect.

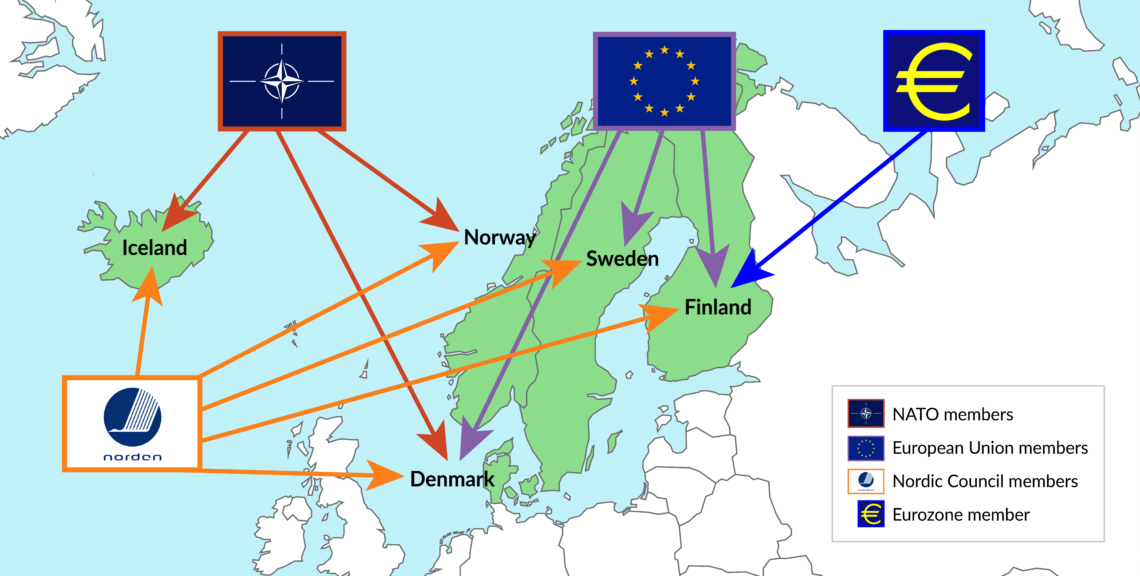

For economic and geopolitical reasons, the various Nordic countries chose different approaches to Europe’s two main postwar integration projects. While Denmark, Iceland and Norway joined NATO, Denmark, Sweden and Finland joined the EU, and only Finland has adopted the euro. It is not easy to see a common Nordic pattern here.

The migration issue has become so deeply divisive because of differences in how these nations see themselves.

The migration issue has become so deeply divisive because of differences in how these nations see themselves. Having a long tradition of welcoming immigrants, Sweden was only too happy to join German Chancellor Angela Merkel in proclaiming that “refugees are welcome.” The mainstream Swedish political parties have also, like their counterparts in Germany, vehemently ostracized those who are critical of admitting migrants. The Sweden Democrats (SD) party has been subjected to the same type of witch hunt as the Alternative for Germany (AfD), only more extreme.

In the other Nordic countries, political parties that were once known as populist and xenophobic have long since been integrated into the mainstream. They serve or have served in government. Feeling there is nothing very strange about this, politicians and media have become increasingly concerned about the Swedish stance.

In a recent talk show on Swedish television, former Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt was taken to task by former Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen. In a friendly talk between the two conservative former politicians, Mr. Rasmussen cautioned his Swedish counterpart that “nothing good can come of trying to isolate your opponents. It will only make them stronger.”

Very true. Much like the AfD has fed off being ostracized in Germany, the SD has grown from six percent in 2010 to 12 percent in 2014, and it may well double its support again in Sweden’s September 9 general election. Since the mainstream parties will not form a government with support from the SD, and a grand coalition is still not possible, it is very difficult to see how a working Swedish government can be formed in the fall.

Ticking time bomb

The political spillover from the migrant crisis has provided ample vindication for those who view Sweden as a bad example. As it was becoming obvious just how large the migrant flows were, Denmark and Norway made it clear that they had no desire to join the welcoming committee. Having maintained a restrictive policy on migration, Finland remains an ethnically homogeneous society and is not as much at risk.

The initial reaction from the Swedish government was to tout its moral superiority and castigate others for not living up to its lofty standards. Then, as the roof began caving in, it made an abrupt about-face. Sweden closed its borders, disrupting commuter traffic between Copenhagen and Malmo via the Oresund Bridge. Adding insult to injury, the Swedish government also brazenly demanded that others must share in the burden of its self-inflicted migrant crisis.

This arrogance stirred up latent resentment within the region of Sweden arrogating to itself the role of Scandinavia’s leading power. Travelers arriving at Arlanda Airport have, for example, been greeted by a big sign saying, “Welcome to Stockholm, the Capital of Scandinavia!”

This hubris goes down badly with neighbors who still remember the legacy of Nordic disunion during World War II.

Pursuing a very “flexible” policy of neutrality, Sweden managed to stay out of the war, watching as Norway and Denmark were occupied by Nazi Germany, and as Finland was struggling for survival in its bloody Winter War with the Soviet Union. The episode still raises hackles, especially since some Swedish politicians have gone so far as to brag about what a smart decision the country made in remaining neutral.

This has not exactly been helpful to Nordic cooperation. A striking illustration of how tense relations have become was provided when it became clear that Brexit would cause the EU-funded European Medicines Agency to leave London, taking 900 jobs with it. As Denmark and Sweden were both in the running to provide a new home for this important agency, the Danish government suggested a mutual voting pact. Sweden refused. After its own bid was defeated, it instead opted to support Italy. The Danes were furious.

In some quarters, the anger is spilling over into contempt and gleeful comments about Sweden’s impending collapse. Although the Swedish economy still looks like a great success, with all the macroeconomic indicators in positive territory, the future costs of the migration crisis are looming. As the burden of supporting migrants that will not and cannot be integrated is shifted onto local budgets, some Swedish counties may need to increase taxes by up to 20 percent. Voices warning of an imminent disaster are being suppressed. Whoever is charged with forming a new government in the fall will have to face this challenge.

Swedish risk

Although the Nordic countries have every reason to be concerned about what is happening in Brussels and to formulate a common approach, such questions hardly register. The issues dominating public discourse are linked to security. While the threat from Russia has brought non-NATO members Sweden and Finland together in close defense cooperation, the threat from the migrant crisis has escalated to the point where neighbors consider Sweden a risk to their own security.

The security issues dominate public discourse.

The most obvious threat is the rapid escalation in new forms of violent crime, ranging from brutal gang rapes, to street shootings, burning cars, police station bombings and first responders being pelted with stones. Two trends combine to prevent serious action from being taken.

One is that politically correct attitudes from officials at the top – including orders not to mention ethnicity in crime reports, a focus on dialogue with hoodlums and an emphasis on sympathy for the perpetrators – have increasingly demoralized members of the Swedish police force. Senior officers are leaving, and new recruitment is far below target. Despite entry requirements having been lowered, slots at the National Police Academy cannot be filled.

The other trend is that Islamism is gaining a firm hold over Sweden’s politics. The country’s self-proclaimed feminist government is providing ample subsidies to organizations affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood that promote establishing a parallel society for Muslims. There is a steady proliferation of suburbs ruled by clans that impose curbs on women’s rights and demand that residents shall have no contact with Swedish authorities. Muslim members of the mainstream parties have also begun calling for Swedish law to be adapted to the needs of Muslims.

One illustration of success in the latter ambition is that the Swedish court system recently recorded its first case of blatant disregard for the core principle of equality before the law. Ruling to dismiss charges against a man for having beaten his wife, the court noted that since the couple had been married according to Sharia law, the aggrieved woman should have turned to the husband’s family rather than go to the police.

Opposite direction

Terrified by the Swedish example, both Norway and Denmark have taken harsh measures to prevent their own countries from being drawn into the same spiral.

The Norwegian government has publicly announced that migrants from Muslim countries must assimilate or stay out, stating that in Norway “we drink alcohol and eat pork, and we do not cover our faces.” The Norwegian foreign office has also leaked an internal memo detailing how Oslo is preparing to suspend the Geneva Convention and close its borders to Sweden, were it to collapse.

A likely outcome is that Sweden is thrown into turmoil.

The Danish government has beefed up its already tough policy on migrants by launching a program of “ghetto destruction,” aiming to tear down apartment buildings in nonintegrated neighborhoods. The program also calls on courts to mete out double penalties for crimes committed in these neighborhoods and halves the benefits of foreigners settling there.

Sweden is still taking in large numbers of asylum seekers and is expected to add as many as 400,000 more migrants through family reunifications. Meanwhile, Denmark is building detention camps and preparing for mass expulsions. While Sweden provides full social benefits even to migrants who are under legal deportation orders, those who are placed in the Danish detention camps have freedom to move but are not offered Danish lessons, since they will not be integrated.

Tipping point

These are the main reasons why there is so little concern in the Nordic countries about Brexit and the EU. Non-EU member Norway has made it clear it will follow carefully what happens with Brexit, with a view to perhaps calling for changes in its own relationship with the bloc. Finland is torn. In 2015, many called for Finland to be the first country to leave the euro. That sentiment has since subsided, but could flare up again. In Sweden, some warn of the risks implied in Brussels’ calls for “more Europe,” but such voices are largely ignored.

The migrant crisis absorbs all energy. To block the SD from cashing in on popular fears, the mainstream parties are rushing to introduce constitutional amendments that will significantly curtail freedom of speech. Swedish democracy and the rule of law are under serious threat.

It is possible that Swedish public opinion may reach a tipping point, turning vehemently against migration and by implication against the EU. The situation is currently so volatile that there could be a substantial swing. While calls to leave the EU are not likely to reemerge, there is plenty of displeasure with Brussels that could be harnessed. Joining the euro can be dismissed out of hand.

It is possible that the SD sweeps up all this discontent and proceeds to support the formation of a minority conservative government, which in turn could embark on mending fences with the other Nordic countries to form a strong bloc against migration. Considering what has already happened in Austria and in Italy, this scenario cannot be ruled out.

A more likely outcome is that Sweden is thrown into protracted turmoil that produces polarization between the hard left and the hard right, with a powerful component of Islamist activism. The prospects for Nordic cooperation will shrink even further, and Brussels will be faced with trouble in the north that adds to its already overflowing agenda.