Bulls, bears and the first quarter of 2021

With average oil prices reaching pre-Covid levels, most financial institutions have adjusted their forecasts during the first quarter of 2021. However, the pandemic has not yet been fully brought under control – and renewed lockdowns could take investors by surprise.

In a nutshell

- Experts predicted a spectacular recovery of oil prices

- Previous ambitious forecasts have been proven wrong

- Under current conditions, the upward trend could hold

Oil prices have come a long way since reaching their lows of April 2020. The rebound has been rapid and impressive; prices are currently similar to those of early 2020, before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The trend has pushed some market observers, particularly financial institutions, to significantly upgrade their forecasts, with some even predicting three-digit prices.

There are sound reasons to be optimistic. However, if history is any indicator, oil-price predictions are often less accurate than weather forecasts. Covid-19, the mother of all market threats, is still alive and kicking, and even mutating. All oil market and economic projections now feature a disclaimer warning about the continued uncertainty caused by the coronavirus, and rightly so. Still, one development appears unlikely even when the pandemic is brought under control: a steep upward trajectory in prices.

Facts & figures

Oil in the first quarter of 2021

- OPEC+ accounts for nearly 40% of world oil supply.

- Oil demand declined by 8.7 mb/d in 2020 and is expected to increase by 5.4 mb/d in 2021.

- The U.S. and China are the world’s largest oil consumers, accounting for nearly 24% and 15% of total oil demand respectively.

- As of May 2021, commercial flights are more than double their 2020 levels (year on year) but still only 65% of 2019 levels.

Aiming high

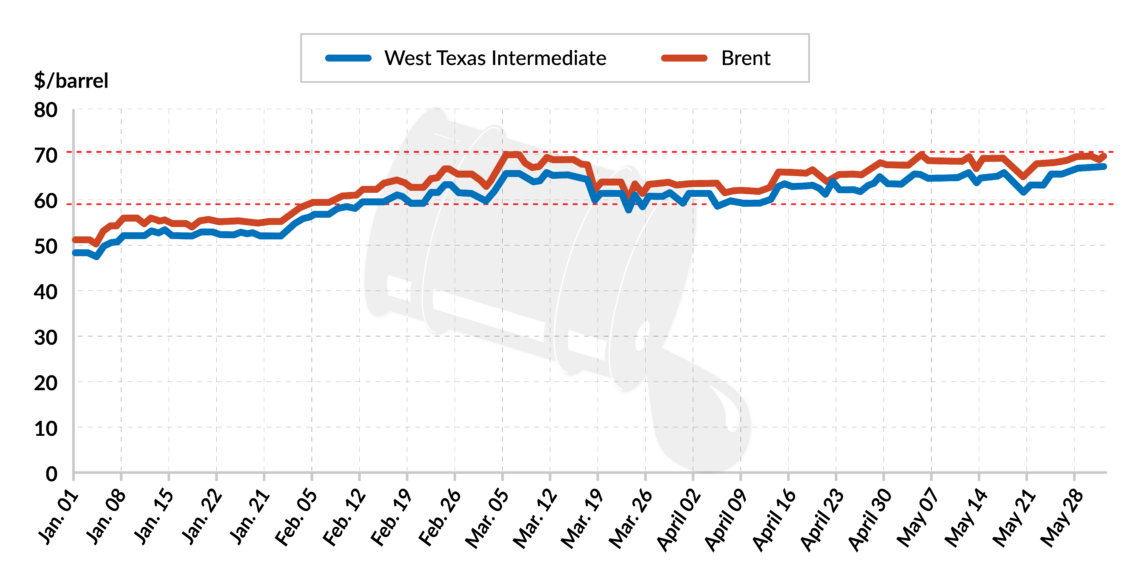

Since February this year, oil prices (Brent) have been consistently trading above $60 per barrel (/bl). Wall Street banks are sanguine about the outlook for the remainder of the year and even further ahead.

Covid-19, the mother of all market threats, is still alive and kicking.

Goldman Sachs expects oil prices to hit $75/bl during the second quarter of 2021, then $80 during the third quarter. JP Morgan even mentioned prices hitting three digits once the global economy fully recovers from the pandemic. Such a rally would be part of a “commodities supercycle,” a current buzzword in the financial community, whereby commodities from iron ore to oil and staple crops trade above their long-term average prices for several years.

Others remain more cautious. The United States Energy Information Administration (EIA), for instance, expects oil prices to average $65/bl in the second quarter of 2021, $61/bl during the second half of 2021, and $61/bl in 2022. The CEO of French oil major Total has suggested that prices between $50-60/bl were more likely.

Improved outlook

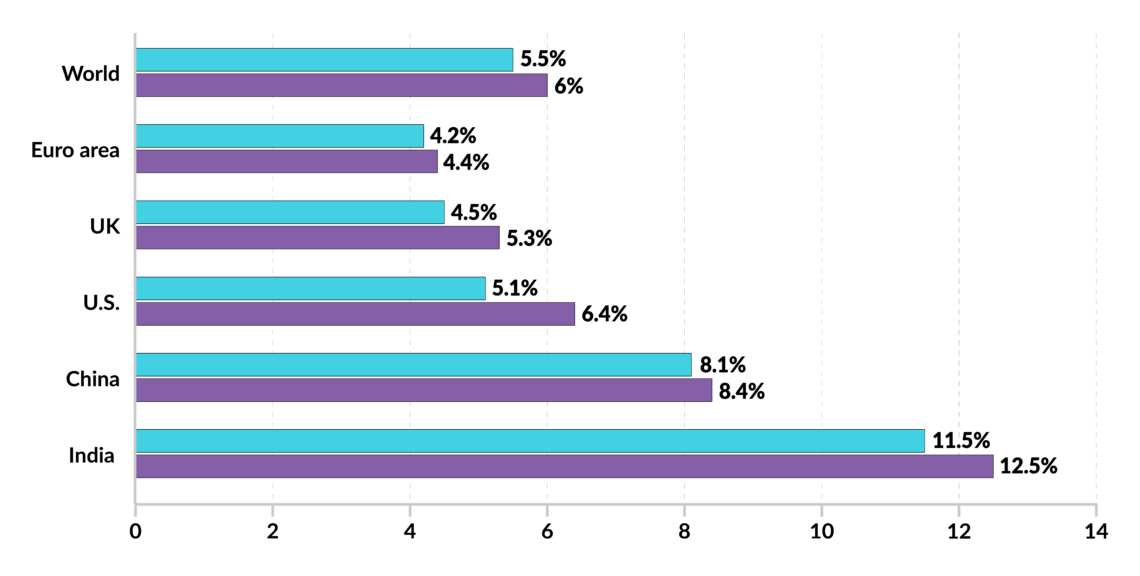

Across the board, economic forecasts are being revised upward. In its April World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for instance, upgraded its forecasts for almost all countries, because of generous government fiscal packages and monetary policies, as well as the vaccination rollout.

The world’s largest economies, the U.S. and China, are the twin engines driving global recovery. Together, they account for more than 40 percent of the world economy and more than 40 percent of the world’s administered vaccines to date. Both countries are racing ahead.

This improved macroeconomic outlook has led most to predict higher oil demand.

In the European Union, the world’s largest economic bloc, the vaccination rollout has picked up and should accelerate economic recovery as restrictions on businesses and mobility ease accordingly. Other pockets of economic rebound continue to emerge around the world. Domestic travel in the U.S. and China is almost back to pre-Covid levels. Full normalization of U.S. travel is expected in 2022, much earlier than predicted before a vaccine was developed. International travel restrictions are being lifted gradually, with countries like Greece opening their doors to tourism for vaccinated travelers and those with a negative Covid-19 test.

This improved macroeconomic outlook has led most to predict higher oil demand. For the first time since at least the summer of 2020, the three major forecasting agencies – EIA, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and OPEC – have all revised their oil demand forecasts upward in their April monthly oil market reports. Traditional disparities remain, with the EIA being the most optimistic and OPEC the most conservative.

Facts & figures

Restrained supply

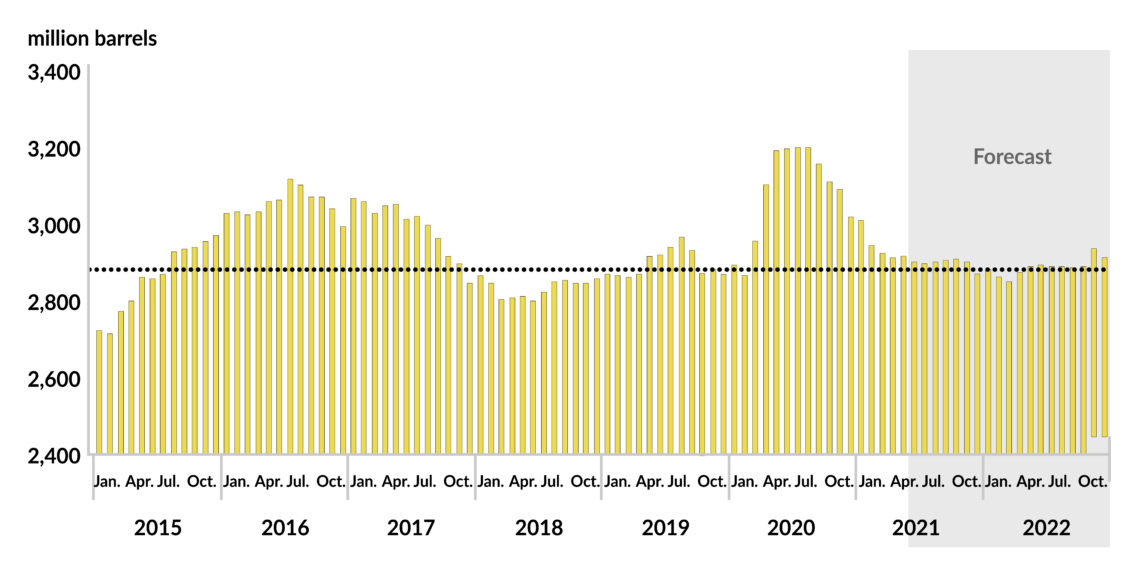

The rebound in oil demand was accompanied by a more restrained supply, which explains the rise in prices. OPEC+ has been carefully tracking oil demand growth. On April 1, 2021, just under a year after its historic agreement to cut 9.7 million barrels per day (mb/d), the producers’ group agreed to ease its cuts by 1.15 mb/d between May and July this year. Additionally, Saudi Arabia said it would relax its voluntary 1 mb/d cuts over the same period. If things go according to plan, by July OPEC+ will have just above 60 percent of the original cuts (6 mb/d) to ease out by April 2022, when the deal is supposed to come to an end.

All those who expected the oil market to return to normality in the first quarter of 2021 have now been proven wrong.

Since OPEC and a Russian-led group of producers came together in December 2016 and became known as OPEC+, their official objective has been to bring commercial oil inventories in line with their past five-year average. Back then, this meant the period between 2010 and 2014; today, it is 2015-2019. Inventories build up when there is too much supply in the market and demand is not growing fast enough to absorb the excess. Inventories are deliberately kept under a certain level when demand grows faster than supply, as it does now. By limiting the number of barrels it exports, OPEC+ has successfully managed to bring inventories levels to their five-year average. Some market observers translate this trend into upward pressure on prices. Based on this metric alone, one can understand Wall Street’s bold forecasts.

Continued uncertainty

The problem, however, is that this is only one aspect of many moving parts in the complex global oil markets. Other elements call for greater vigilance. First, when it comes to inventories, the figures reported are those of the OECD. The accumulation of inventories in the developing world, for example in China and India, is not publicly known and whatever is reported is simply guesswork. Also, the five-year average is by itself misleading, not only because it is a moving target, but also because it includes the post-2014 oil price collapse period (2015-2017) when inventories reached record levels. In this respect, the five-year average of 2014-2019 is already inflated by historical norms.

Second, the continued uncertainty caused by Covid-19 could still affect demand. India shows how forecasts can be thrown off track. In its April publication, the IMF expected it to be the only large economy to achieve double-digit growth this year. However, soon after that outlook was published, and just one month after the Indian health minister announced that the country was “in the endgame” of the pandemic, infections and death rates reached record highs. India’s economic outlook has been downgraded accordingly. In its May economic outlook, the OECD revised India’s economic growth to 9.9 percent, down from 12.6 percent in the organization’s March report.

Facts & figures

On the supply side, OPEC+ has accumulated record spare capacity that will make its way into the market in the coming months. This is in addition to other potential supplies from within the group (for example Libya and Iran, which are exempt from output restrictions) and from beyond, primarily private production in North America. Despite the ongoing skepticism of market commentators on the recovery of U.S. shale oil, there are positive signs. In the latest survey carried out by the Federal Reserve Bank of Texas, the business activity index – the survey’s broadest measure of conditions facing energy firms – reached its highest reading in the measurement’s five years of existence.

Outlook

On balance, optimistic voices are overtaking more pessimistic ones. Still, “exceptional uncertainty” – in the words of the IMF – remains, as recovery continues to depend on the course of the pandemic. Currently, the hope is that it will be over by the end of the year at the latest. It is worth remembering, however, that all those who expected a return to normality by early 2021 have now been proven wrong.

With this in mind, it is wise to expect a sustained recovery in oil markets where prices continue to hover in the current range, but without sharing the high expectations of the bulls of Wall Street.