Oil market rebalancing and the future of ‘OPEC+’

In 2016, some oil-producing countries that were not part of OPEC joined with the cartel to agree on production cuts to shore up oil prices. At the time, plenty of observers were skeptical the group would hold together. But not only did it manage to implement the reductions (and extend them twice), it has put a floor under oil prices.

In a nutshell

- The “OPEC+” group has managed to put a floor under oil prices

- It is still a long way from achieving the price and inventory levels it wants

- The alliance benefits Saudi Arabia and Russia, its two main architects

- There is little risk of the group breaking up before the end of next year

Around the world, experts continue to debate the stability of oil markets. Stability, however, means different things to different people. Lately there seem to be two popular definitions.

First, economists talk about balanced, stable markets when supply and demand are in equilibrium or, more generally speaking, when supply and demand grow at the same rate. Such a situation can easily be recognized by the absence of sudden, violent price changes and by the presence of stable inventories. In that sense, between 2011 and 2014, the oil market was stable. Then the market was thrown into instability by shale oil from the United States and needed readjustment, or “rebalancing,” to use the popular phrase. Economists, of course, would simply assume that the markets could take care of this themselves, without outside help.

More politically minded oil analysts increasingly discuss stability with reference to the alliance between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers. This alliance, also known as OPEC+, was formed in 2016, to “rebalance” the market in a way that benefits the countries in the group. Analysts ask whether this alliance will hold, and if it will do so long enough to achieve its goals. While OPEC+ says it advocates oil market equilibrium as set out in the economic definition, the group aims to achieve a market “rebalance” at a higher oil price than what the system would have generated by itself.

Consequences of the alliance

The emergence of OPEC+ has caused all sorts of adjustments: OPEC+ production cuts targeting 1.8 million barrels a day (mb/d), oil price volatility, increases in U.S. shale oil production and market share, and changes in inventories, among others.

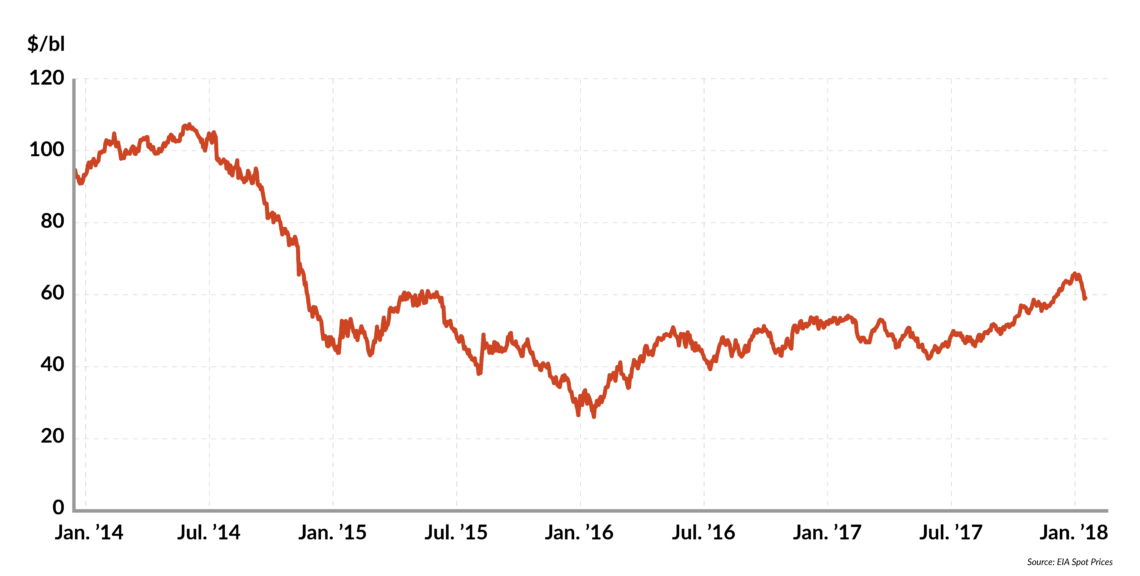

With its agreement to cut production, OPEC+ has managed to put a floor under oil prices. Prior to the deal, oil prices were heading below $40 a barrel. Prices and inventories, however, have not settled. Originally, OPEC thought it could “rebalance” the market in six months, but 18 months later, uncertainty and adjustment continue.

Facts & figures

WTI crude oil prices

So, the big question is: What will happen next? To answer this, we should look at how stable the OPEC+ alliance is.

OPEC+ strengths

To date, the OPEC+ deal to restrict oil production has been extended twice (in May and November 2017). At its last meeting in 2017, OPEC+ announced that the deal would be extended throughout 2018, with a possible revision in June 2018.

Many believe that the OPEC+ coalition is fragile and unlikely to survive past June 2018, let alone until the end of the year. Such skepticism echoes the predominant sentiment back in 2016 when the deal was first announced. However, the past 18 months have confirmed the coalition’s determination: OPEC has achieved more than 95 percent compliance. Russia, which leads the non-OPEC part of the alliance, has proven to be a reliable partner. It is therefore likely that the agreement will survive until at least the end of 2018.

But will this be enough? Is an exit strategy in place? And if so, what does it look like?

Facts & figures

Key OPEC+ facts

•On Nov. 30, 2016, OPEC announced a coordinated production cut of approximately 1.2 mb/d, limiting its production to around 32 mb/d

•A week later, 10 non-OPEC members, led by Russia, also committed to reducing their combined output by an additional 600,000 barrels per day (bpd), bringing the total cuts to 1.8 mb/d, effective Jan. 2017

•The EIA forecasts U.S. crude oil production will average 10.6 mb/d in 2018, surpassing the previous record of 9.6 mb/d set in 1970

•Nigeria and Libya have been exempted from OPEC+ production cuts

•In December 2017, Venezuela’s oil production fell to 1.6 mb/d, meaning it has reduced production by 500% of the amount required by the OPEC+ deal

Premature victory?

OPEC is increasingly vocal about the substantial decline in the inventories of the rich countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This gives the impression that the markets are close to rebalancing and, assuming sufficient demand growth, can therefore be left to themselves. If this is true, the alliance could declare victory, and the OPEC+ cuts could gradually be phased out.

Demand may not grow fast enough this year for OPEC+ to consider ending the cuts.

However, declaring victory so early is risky, primarily because forecasts for growth of both supply and demand, as well as the speed at which inventories are declining, suggest the “rebalance” OPEC+ is looking for is not right around the corner.

The more demand increases, the earlier it will absorb the excess supply currently taken up by OPEC+ cuts. However, there is a significant divergence in this year’s demand growth forecasts, the most conservative being the International Energy Agency (IEA) with 1.3 mb/d and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) at 1.7 mb/d. Given recent price increases, demand may not grow fast enough this year for OPEC+ to consider ending the cuts.

In terms of supply, forecasts are more consistent, with strong non-OPEC+ growth expected, whether from shale or conventional oil, particularly from Canada and Brazil.

The more controversial issue is probably OECD oil inventories. Back in November 2017, Saudi Energy Minister Khalid Al-Falih announced that those inventories have “passed the halfway mark on the journey towards achieving the five-year average.”

It is true that inventory levels have been declining, but the numbers should be put into perspective. When OPEC+ began its drive to reduce inventories to the five-year average, the reference was to the 2010-2014 period. This benchmark has moved, with the reference now the average over the past five years. Inventories still have a long way to go before reaching the 2010-2014 average.

Mutual benefit

Oil prices are moving higher, just as OPEC+ would like, but for the above reasons, they are unlikely to reach the coalition’s desired level by the end of 2018. That gives its members a strong incentive to continue cooperating till the end of the year. To quote the oil minister of the United Arab Emirates, “directionally, we have affected the market, but we are not there yet.”

The deal makes sense to its two main architects: Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Furthermore, the deal still makes sense for its two main architects. Saudi Arabia needs the money: the International Monetary Fund (among others) cites slumping oil prices as the primary risk to its economy. Russia also benefits. According to the World Bank, Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP) went from a decline of 2.8 percent in 2015 to a growth of 1.7 percent in 2017. Its federal budget went from a deficit to a surplus over the first nine months of 2017, and higher oil tax revenues have been generated thanks to a royalty tax imposed on a sliding scale that changes (primarily) with the oil price. These numbers play well ahead of presidential elections later this year. Geopolitically, the deal has increased Russia’s influence in the Middle East. So economically and politically the deal makes sense. Why change it?

Taking all this into account, the coalition will probably remain in place until it has achieved the “rebalancing” it wants. It looks like this will last well into 2019.

Eventually, demand will catch up and there is the risk of a disorderly breakup and a renewed war for market share. However, some form of continuous collaboration is more likely. It could take the form of a “friendly” producers’ association that closely monitors the market.

Production risks

Some would argue that pressure on some OPEC+ countries to increase output is higher this year. Russia is one example. Russian companies are not happy about the cuts; because of their tax code, they need high volume to shorten the payback period for capital expenditures over the past few years – and they are not happy about losing market share to higher-cost producers. Russian President Vladimir Putin may listen to them.

More important, however, is the risk of supply disruptions from within OPEC that could ease such tensions. The biggest contenders are Venezuela, Iran, Nigeria and Libya. Venezuela has been the most involuntarily compliant country with the OPEC+ deal because of its economic difficulties, financial sanctions and social unrest. The situation could get even worse.

If supply disruptions cause prices to shoot up dramatically, OPEC+ may revise its production targets.

The economic grievances that sparked the largest demonstrations in Iran since the 2009 Green Movement continue to sow discontent. And with new U.S. sanctions looming, Iran’s ability to expand its exports and attract international investors looks even more questionable. Nigeria and Libya have been on a roller coaster the last few years, but they are unlikely to sustain the production growth they achieved toward the end of 2017, since the fundamental problems that led to previous supply disruptions have not been resolved.

In brief, there are more downside than upside risks when it comes to supply. However, if supply disruptions cause prices to shoot up dramatically, OPEC+ may revise its production targets.