The United States should rein in the global tax bureaucrats

President Trump was right to disrupt the G7’s efforts to promote “fair, progressive, effective and efficient tax systems.” The goal may seem innocuous, but it is quite the opposite – favoring large, intrusive governments at the expense of individual economic freedom.

In a nutshell

- The G7 and the OECD are pushing tax policies that favor intrusive governments

- Unharmonized, porous tax systems foster global competition and economic growth

- Centralized exchange of tax information will strongly penalize American companies

This opinion was co-written by James M. Roberts.

United States President Donald Trump shook up the recent G7 meeting in Canada, declining to sign a joint statement with the other countries’ leaders. Considering the content of that statement, it is clear the president made the correct decision.

Admittedly, the clash at the summit over the shape of future trade relations among the G7 countries is troubling. When it comes to tax policy, however, the president was well-advised to continue his disruptive tactics and oppose the statement’s endorsement of “international efforts to deliver fair, progressive, effective and efficient tax systems.”

Such efforts may seem innocuous, but they are quite the opposite. The G7 is promoting a one-size-fits-all approach to tax policy, which unambiguously favors larger, more intrusive governments at the expense of individual economic freedom.

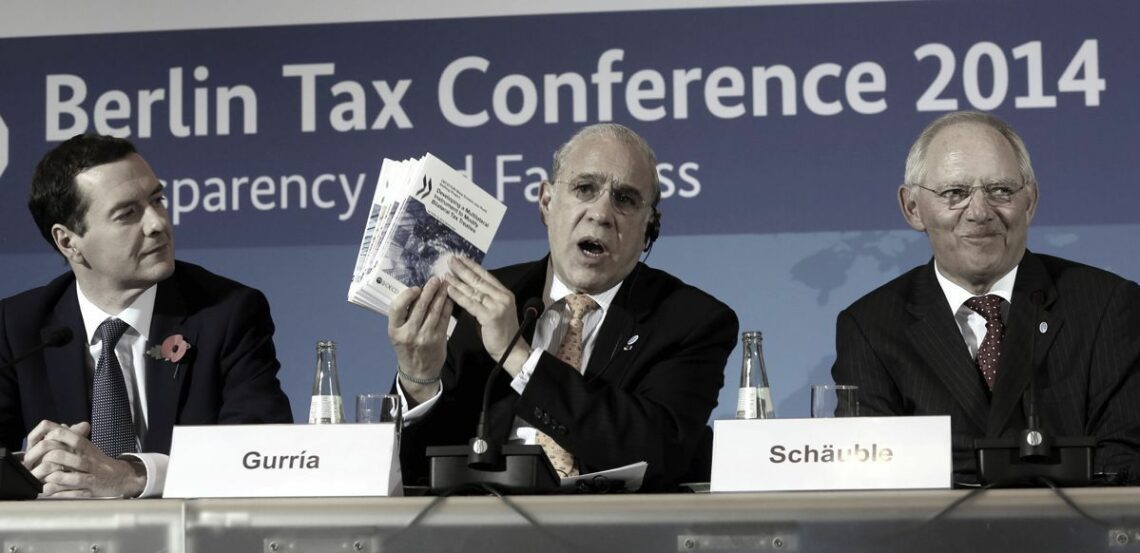

Here it is only following the lead of international policy organizations, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These platforms have been co-opted by tax bureaucrats, who use them to advocate higher and more intrusive taxation. In the case of the OECD, its Centre for Tax Policy and Administration is aggressively pushing its “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)” project, regulators’ latest attempt to increase taxes on international businesses.

Extraterritorial fixes

The G7 summit statement waxes eloquent on the virtues of freedom, democracy and the rule of law, but then quickly pivots to policies directly at odds with these valuable and worthy goals.

The communique recommits the signatories to promote “the global implementation of international standards and addressing base erosion and profit shifting.” The BEPS project aims to centralize and harmonize global tax rules, with the goal of increasing effective tax rates on international firms by discouraging tax planning. The project was born out of a renewed concern among tax collectors that sometimes mismatched international tax systems allow some corporate profits to go untaxed.

Porous tax systems generate competitive pressures that are a boon to global economic growth.

The world’s sometimes porous tax systems, however, have the virtue of generating pressure to keep business taxes in check. These competitive pressures have been a boon to global economic growth and investment. They are undermined by the efforts described in the G7 statement, which is intended to motivate countries to crack down on tax planning through intrusive extraterritorial “fixes” to the supposed BEPS problem.

Digital tax

One outgrowth of the BEPS project is an interim digital transactions tax proposed by the European Commission. Aimed at the same perceived problem as the BEPS project, the new tax would be a 3 percent levy on revenue from online advertising, sale of user data and facilitated user interactions. It is nothing more than a poorly disguised attempt to extract additional revenue from large companies based in the United States, however negligible their presence may be in a given country.

Since the reality is that global implementation of the international standards prescribed by the OECD is a distant dream, the Commission is proposing a go-it-alone strategy. The EU’s new digital tax, however, is built upon the work done in the BEPS project. This explains why the tax bureaucracies of the OECD’s European Union members are heavily promoting extraterritorial and unilateral departures from the standard global tax system.

Under President Barack Obama, the U.S. declined to sign the Multilateral Convention implementing the BEPS project, although the Treasury Department did promulgate new regulations to comply with new country-by-country (CbC) reporting, one of the project’s recommendations. The Obama administration also regularly signed on to sweeping language about international tax standards.

Country-by-country reporting is a new international system for centralizing and automatically exchanging taxpayer information. This treasure trove of confidential data (much of it provided by the U.S.) has given potentially unfriendly, revenue-hungry states the information they need to raise taxes unilaterally on American companies.

In its fervent ambition to eliminate tax planning, the OECD may also be inadvertently opening the door to global double taxation. Ironically, curbing double taxation was one of the OECD’s most important and beneficial early contributions to the global economy.

Curtailing privacy

Even more intrusive than the CbC rules is the OECD’s new protocol amending the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters. The Protocol is one element of a new and complicated international tax information-sharing regime.

Fortunately, as in the case of BEPS, the U.S. has not fully implemented the Protocol. It would mandate that the Internal Revenue Service automatically share bulk taxpayer information with governments worldwide, many of which – like China, Nigeria and Russia – are either corrupt or hostile to the U.S. and other Western countries, or both.

Together with other reporting requirements such as the CbC, the already-voluminous compliance costs imposed on financial institutions and international businesses would only increase under the Protocol. These requirements could also have the pernicious side effect of curtailing financial privacy, putting Americans’ private financial information at risk of being used by foreign governments for purposes of expropriation.

Opposition research

To date, fortunately, the U.S. has mostly resisted the constant push by the OECD, the United Nations and the G20 to increase worldwide tax revenue. However, the American taxpayer continues to foot the bill for a large portion of their research. Although it is only one of 34 member states, the U.S. provides more than 20 percent of the OECD’s budget. As the largest funder of its research, the U.S. should direct the OECD to turn its focus toward a more diverse set of policy goals, such as ways to streamline and shrink the size of government and lower taxes.

International bureaucracies are not being held accountable by member governments.

By their aggressive, persistent and lopsided advocacy of more taxation, global organizations such as the OECD have demonstrated that they have broken free from the member governments that fund their operations. These international bureaucracies are, for the most part, not being held accountable by member governments, or have even been egged on by some to pursue an agenda to undermine U.S. policy objectives. The EU digital tax and the new information-sharing proposals are vivid examples of anti-American policies funded to a significant degree by U.S taxpayers.

It is in this context that President Trump took the unprecedented step of withholding approval of the G7 statement. The president should continue to send strong messages that the U.S. does not support the G7 or OECD goals of focusing exclusively on raising taxes.

Sending a signal

In the absence of a new research agenda, the American delegation to the OECD should continue to shake up the status quo. It should announce that the U.S. will block any new voluntary contributions that could be used to fund OECD research focused on urging member countries to increase taxes and implement more intrusive tax collection methods. The Department of Treasury should also take the necessary steps to rescind the country-by-country regulations and remove the U.S. as a signatory to the Protocol.

To follow up on the momentum of the historic and positive tax reform of 2017, the U.S. should also stick to its strategy of encouraging businesses to grow and produce in America. The new, lower corporate tax rate and other business reforms, such as “expensing,” have combined to make the U.S. one of the most attractive new investment locations in the world.

The OECD’s base erosion project would be a step backward for the U.S., reducing the country’s attractiveness to investors. Rather than luring commerce with business-friendly policies, BEPS creates new barriers, making life more difficult for entrepreneurs and incentivizing them to leave and do business elsewhere.

By making it clear that the U.S. does not support the OECD or the G7 in their quest to raise taxes on business, the Trump administration is sending a strong signal to the global community: America is open for business.