Russia’s possible motivations in the Skripal case

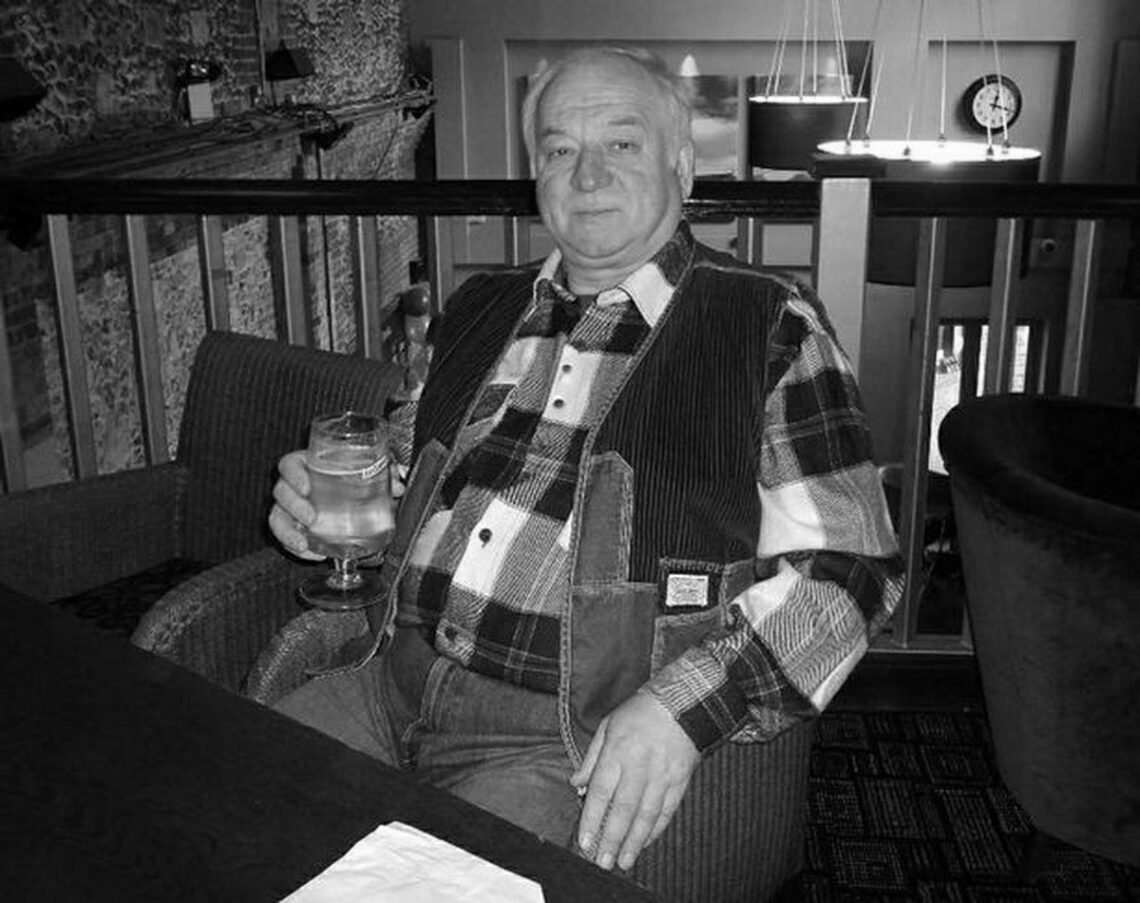

It is widely accepted that Russia was behind the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal. But the question remains why it should commit such an act, with so little to gain. Several explanations are plausible – that it was an attempt by President Vladimir Putin to show he is in control, or a gambit by his enemies to undermine him.

In a nutshell

- Russia appears to have had little to gain from the Skripal poisoning

- Several explanations involve internal Russian political machinations

- It may also be an attempt to gauge reaction to a chemical attack on British soil

Several people have lost their lives under mysterious circumstances in the United Kingdom over the past few years. They have had a few things in common: connections with Russia (either in business or the intelligence services), residence in the UK and a peculiar demise. UK Home Secretary Amber Rudd has announced an investigation into Russian involvement in the deaths of 14 people. Some of the names are well-known, such as Alexander Litvinenko, Boris Berezovsky and Georgian billionaire Badri Patarkatsishvili, a business partner of Berezovsky’s. Some are less familiar, like Alexander Perepilichnyy, a 43-year-old financier who died after a mysterious heart attack in 2012. He had blown the whistle about fraud by senior Russian officials. After his death, elements of a rare poison were detected in his body.

Each case is slightly different, but in almost all of them the blame fell on the Kremlin. Where former intelligence officer Sergei Skripal’s case differs from the others is the scale of the reaction by Western governments, which surprised not only Russia but also many skeptical analysts in the West itself. Though the UK’s accusation that Russia was behind the poisoning was widely recognized as well-founded, the question remains: why? Why would someone from the state apparatus be interested in murdering people whose anti-Russian activities were well-known and relatively harmless, especially since the victims’ insider knowledge was long out of date?

Is the leader behind it, or rather internal enemies who want to undermine him in the international arena?

When it comes to highly centralized or authoritarian systems, one must always ask about the responsibility for particular state actions. Is the leader behind it, or rather internal enemies who want to undermine him in the international arena? In Poland, the most famous political murder of the 1980s was the assassination of Jerzy Popieluszko, a priest, by the regime of General Wojciech Jaruzelski. To this day, there is a debate about whether the murder was ordered by Jaruzelski’s team or by his political rivals in the corridors of power.

The same logic applies to the Skripal case. It cannot be ruled out that elements within Russia’s power structure engineered the incident so as to “implicate” President Vladimir Putin – in which case, the attempted murder occurred against his will or without his knowledge.

A move against Putin

Let us consider some of the ensuing scenarios. First, the Skripal case may be like the infamous horse’s head in Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather, a message sent to the Russian head of state. It is a warning that he does not control the security apparatus, which can carry out acts that can lead to serious tensions between Russia and other states without his knowledge or approval.

There is another possibility: someone within Mr. Putin’s circle or even the Russian president himself thought that after the recent elections – which just confirmed his authority – an attempt could be made at reconciliation with the West. Four years after the annexation of Crimea, it is clear that Russia has concluded that the West is feeble and unable to cooperate effectively. The UK, in particular, is at its weakest in recent memory due to the faltering Brexit negotiations and an inept Labour opposition, whose leader is openly suspected of cooperating with the Soviet secret police. These conditions could portend success for an attempt to repair Russia’s international relations. In this scenario, Mr. Skripal’s attempted assassination was a brake applied by opponents of such an arrangement.

Finally, one can imagine that a group of people in the security apparatus, independently of the political leadership, decided to impose the proper punishment for treason. The Russian intelligence services have a powerful internal code that, in principle, extends back generations to the Soviet KGB and the tsarist secret police (the Okhrana). It is a very closed system.

Please note, however, that in each of these variants, the political leader is still responsible for any collateral damage. From this point of view, the recent explanation by some Western diplomats that “it’s not Putin; it’s a plot against him,” may broaden our understanding of authoritarian systems, but does not make much of a difference. Any leader who tolerates such methods must answer for the political system he created.

The stock explanation for this kind of international “hit” is that it is standard intelligence service doctrine – the only possible outcome of betrayal is death. Even when the treason occurred many years earlier, it sends a simple message: “the corporation does not forgive.”

Political motivations

Political analysis suggests other explanations, however. Typically, the greatest fear of Russian leaders is that they might be ousted with the connivance of the security services. The moment they sense any doubt about their leadership, their impulse is to jerk the reins and bring the security institutions to heel – short-circuiting any possibility of a palace coup.

It might be an attempt to position the UK as a weak link in the U.S.-led international system.

Another possible political motivation for poisoning Mr. Skripal and his daughter would be strengthening Russia in the global arena. For example, it might be an attempt to position the UK as a weak link in the U.S.-led international system. Russian infiltration of expatriate and financial circles in London also point in this direction. In this variant, London could be portrayed as a weak and unreliable ally, potentially compromised and not even capable of providing security to defectors from the Russian side.

Another political explanation – perhaps the most shocking – is based on recognizing what makes the Skripal case different from the others. In this scenario, the potential threat to British civilians by using a nerve agent in a densely populated area is by no means coincidental. Under this reading, the attack was not primarily directed against a former colonel in Russian military intelligence. Instead, it is a crucial field test of the so-called Gerasimov Doctrine.

General Valery Gerasimov is chief of the Russian General Staff and author of an important text on modern war that appeared in the February 2013 issue of Military-Industrial Courier – an important trade publication in Russia’s defense sector. Gen. Gerasimov’s ideas were later developed and elaborated by several Russian strategists. In the simplest terms, they deal with the operational and legal practicalities of conducting hybrid war. The Skripal case is a particularly interesting application in its legal aspects, since the operation was conducted in the opponent’s territory – and not on the sparsely populated periphery but at the center – with a rare and highly toxic chemical weapon.

Studying destabilization

Since the deliberate intent of the Russian state to commit a chemical attack on foreign soil cannot be proven, the aggrieved party has no basis for declaring war in the traditional sense. But a peculiar sort of armed conflict is taking place – a hybrid one. The enemy can observe what social reactions each action brings. With practically no serious costs (in contrast to the use of chemical weapons in traditional wars), the attacking side can test the effectiveness of operations and the international and media response with near impunity.

The more opponents’ reactions are dominated by fear, the more these hybrid-war probes can be considered successful.

This last aspect is most important. A crucial element of Russia’s (and also China’s) influence operations in the West – both in the military and propaganda context – is observing social and political reactions. This “feedback” provides important information on fears, vulnerabilities and resilience of potential adversaries. The aim is to learn how to destabilize the political and social systems of a given state.

The more opponents’ reactions are dominated by fear, the more these hybrid-war probes can be considered successful. This should be a top consideration for decision makers in the democratic world. Their ability to respond to modern hybrid threats – new “smart weapons” designed to yield information about potential weaknesses – will minimize their risk of sudden destabilization.