Post-Covid recovery is not the main challenge ahead

The statistics describing the world economy three months after the lockdowns seem reassuring: We have not had a V-shaped recovery, but GDP growth in the second part of 2020 appears to be firming up. However, trouble is brewing in post-pandemic labor markets.

In a nutshell

- Data shows a significant economic rebound is underway across the globe

- A Covid-19 vaccine is unlikely to cure the problem of insufficient growth

- Post-pandemic labor markets may prove the most unstable

Hopes for quick recovery have vanished. After the 2020 March-May lockdowns crippled the world economy, some analysts were betting on a V-shaped recovery. Covid-19 would soon come under control, they argued, and extraordinary government plans (based on assuming massive debt) would have softened the shock and prevented business from major blows; economic activities could resume normally. As we know, things turned out differently.

Covid-19 is not under control, vaccines are unlikely to be available until sometime next year and many companies have gone belly-up. Nevertheless, it has not been a catastrophe.

Better than expected

The data shows that there has been a significant rebound. For example, after an annualized 33 percent drop in gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter of this year, the United States economy is expected to expand by 26 percent in the third quarter and post an overall 5 percent contraction for the entire year. This is not the outcome that many people had been hoping for, of course. Yet, if these predictions are confirmed, they are far better than what large portions of the public had feared only a few months ago.

Facts & figures

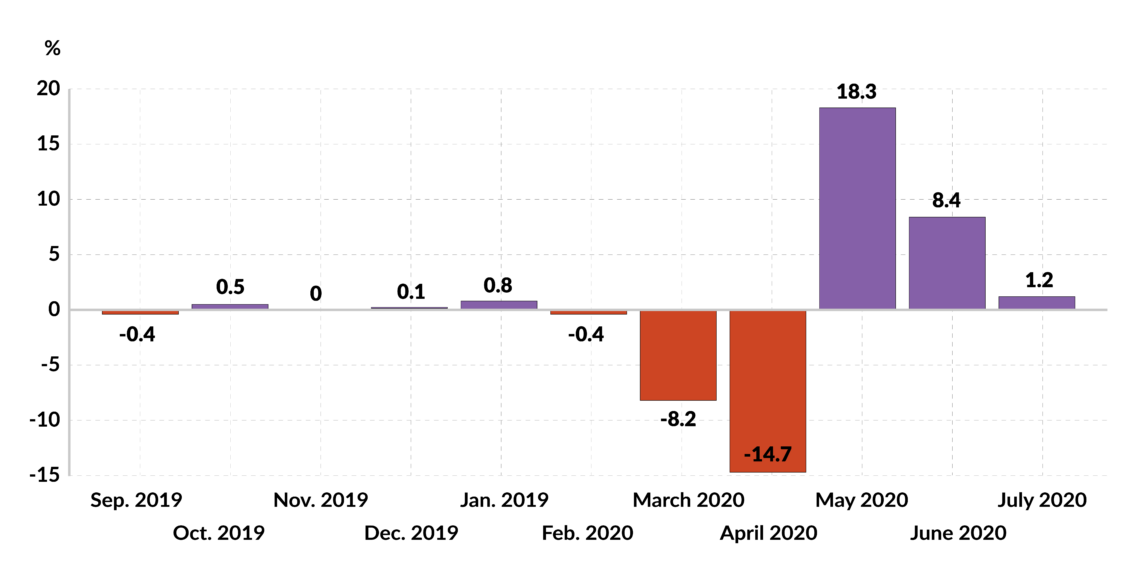

The data shows consumer confidence on the rise. Last June, U.S. retail sales rose 8.4 percent and continued to grow (moderately) in July. The upshot is that at the end of August, consumer spending was where it had been before Covid-19, except for restaurants. However, U.S. GDP growth is expected not to exceed 2 percent next year, even though housing is booming (that is where a large amount of the easy money is going, courtesy of the Fed).

The outlook is less favorable in Europe. Its drop in economic activity has been deeper and the rebound much weaker than what is required to bring the economy closer to pre-pandemic levels. Europe’s 2020 GDP is predicted to finish 9 percent lower than in 2019, but a 6 percent growth rate is expected for 2021.

Even when production reaches pre-Covid levels – around mid-2022 globally and probably one or two years later in the West – the post-pandemic labor market will not follow.

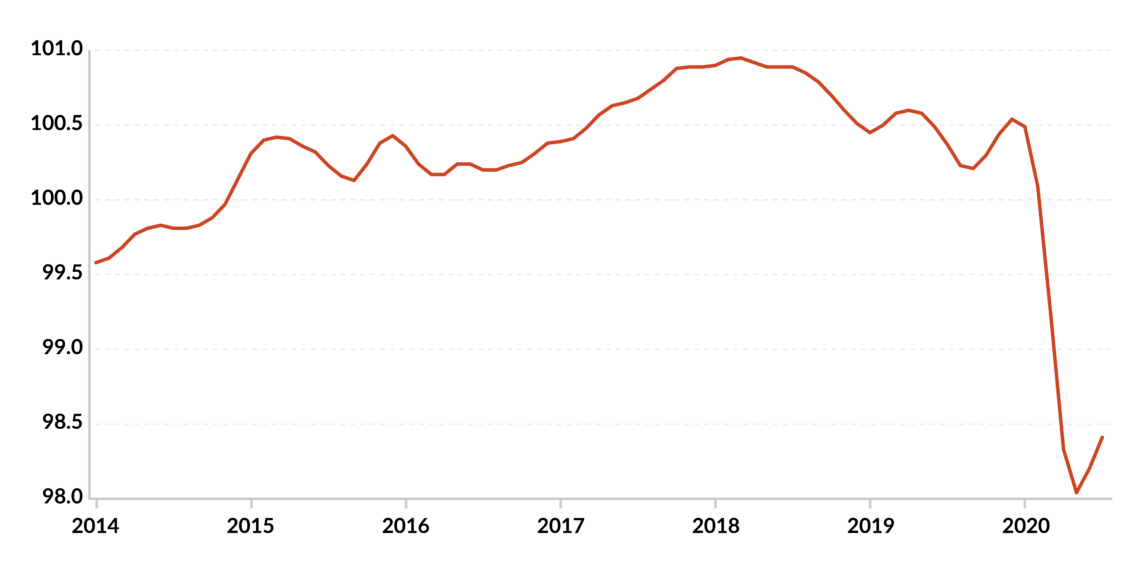

Once again, optimism relies on consumer spending: according to the European Commission’s data, consumers are no longer scared. In particular, consumer confidence is 50 percent higher than during the March-April panic and just a few percentage points below the long-term trend benchmark.

So, is the world economy back on track? Will the West follow China, which is set to record a positive GDP growth rate even in 2020 and presumably, expand by 5 percent to 6 percent in 2021? This report paints a less rosy picture of the future of the Western economies. And the coronavirus pandemic might not be the greatest challenge.

Lurking problems

One partially hidden truth and two variables will play a critical role in this respect. The hidden truth regards the post-pandemic labor market.

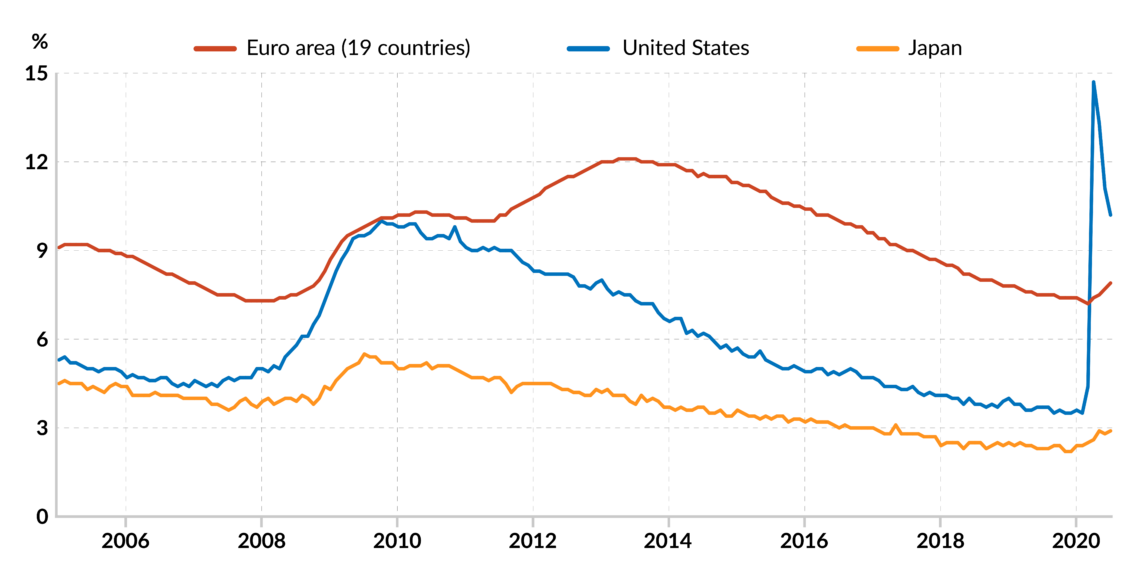

As mentioned earlier, the March-May lockdowns forced most companies to reduce their activity significantly. Many have stopped operating and are unlikely to restart. Massive layoffs have followed both in the U.S. and Europe, but less in China, where anecdotal evidence suggests that the labor force has experienced drastic cuts in wages. We suspect that even when production reaches pre-Covid levels – around mid-2022 globally and probably one or two years later in the West – the post-pandemic labor market will not follow. Many workers are still registered as employed because they accepted part-time jobs hoping to revert to full-time positions. They will be disappointed.

On one hand, companies will tread cautiously, lest they are caught wrong-footed by future negative shocks. Established and new firms will strive to replace workers with fixed capital. Machines have no need for social distancing or designing new organizational schemes for health reasons. Also, they are less likely to be affected by new waves of regulation. If worse comes to worst, below-capacity utilization is still cheaper than having idle workers on the payroll or being in a hiring-firing mode.

On the other hand, the unskilled layers of the working population will not be absorbed by the traditional shock absorbers: main street, family businesses and the national civil service. Unskilled workers – many of them young people – will be left behind and may stir tensions that the policymakers are not ready to confront, let alone solve.

Scenarios

The two mentioned variables have to do with Covid-19: the relevance of the so-called “second wave” – its intensity and the likely response by the authorities – and the timing of the production of effective vaccines. These variables remain unknown.

Although France’s president Emmanuel Macron has expressed his readiness to impose a new total lockdown, other governments are more cautious. Most likely, their responses to the worst scenarios will focus on selective lockdowns. Yet, one wonders what that means and which industries could be hit, and for how long. In the meantime, the recovery will stall. In other words, we see that a V-shaped recovery is out of the question and that the best we can hope for now is a relatively smooth upward path during the next two or three years.

Luckily, a W-shaped future is also unlikely: governments have run out of ammunition and seem to have realized that public opinion would not abide a new freeze. That may rule out another precipitous drop in production. However, people are questioning politicians’ performance and are calling for contingency plans instead of eyewash. This is the key. Thus far, policymakers have been unable to provide convincing answers and the public worries that it would not take much to bring the economies to their knees. Such fears do not amount to a crisis yet but are enough to hold down consumer spending and ensure that the recovery remains gradual and partial.

No silver bullet

This also explains why we suspect that the vaccine will not make a huge difference if offered. As mentioned earlier, the trauma of coronavirus infections and the lockdowns have exposed the political elites’ and their advisors’ incompetence. This public awareness helped nip the V-shaped recovery in the bud and will not disappear with the advent of a vaccine – even as economies have been conditioned by skyrocketing public indebtedness and showers of subsidies.

So, what should one make of the figures? The good news is that the worst is behind us. Although policymakers have been unable to work out a road map, they have run out of their traditional self-defeating policy solutions and probably learned what to avoid in the future.

Retail sales have picked up (and savings rates dropped) during the past three months, which means that most people are unwilling to accept much lower living standards. The less comforting news is that if consumption goes back to pre-Covid levels, but production lags, the result will be higher inflation or – more likely – lower investments.

Third scenario

But this is only part of the story. We fear a third scenario that may emerge toward the end of this year if the figures show that unemployment remains high and closer scrutiny reveals that the official data may underestimate the gravity of the situation.

Under such circumstances, retail sales statistics will be heading south, as new poverty advances and social tensions become more acute. Beijing has relied more on price adjustments in the labor market and less on various forms of public expenditure (significant funds have been allocated to the construction industry and infrastructure, though), China will be spared.

If our concern about massive unemployment is confirmed, many Western leaders will be taken by surprise. They may panic. Whatever they are likely to do next – increase debt or taxation to finance an ever-larger welfare state – it will prove wrong.