Saudi Arabia’s royals are readying a revolution from above

The heir to the throne of Saudi Arabia wants to diversify the kingdom’s oil-based economy and make it one of the 15 biggest in the world. As Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman lines up funding for his project, many wonder if the monarchy is ready for reforms that are nearly certain to upset its social and political order.

In a nutshell

- Saudi Arabia’s king and his anointed heir plan to diversify their oil economy and make it one of the world’s 15 biggest

- The program is to be financed by selling a 5 percent stake in Aramco, the state oil company

- This revolution from above may have far-reaching social and political consequences, not all of them intended

Over the course of three years, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, often referred to as MbS, has taken modest steps toward social reforms. More importantly, he has announced a vision for an economic overhaul that, if implemented, would radically remold the principalist kingdom.

Many in the Middle East and elsewhere perceive the crown prince as a ray of hope for a region mired in fratricide wars and political turmoil. While launching bold initiatives on the home front, he is conducting an active foreign policy. Its goal is to assert his Sunni Muslim kingdom’s regional leadership and thwart Iran’s attempts to create a “Shia crescent” – a network of allies and proxy forces strung across the heart of the Middle East, from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea.

Lofty vision

What remains to be seen is whether oil-dependent, religiously strict Saudi Arabia can morph into a modern economy in a matter of years. Such a transition would require rapid, profound changes in the way of life of Saudi citizens. Is the monarchy ready for reforms that are highly likely to upset its social and political order? Can a still largely tribal society with an entrenched religious establishment be dragged into modernity?

Born in 1985, MbS was his father’s right-hand man from the days when future King Salman bin Abdulaziz was merely the governor of the Riyadh region. Upon his coronation in 2015, the king appointed the son as the minister of defense and made him second in line to the Saudi throne, after his older cousin, Muhammad bin Nayef. Two years later, Mr. bin Nayef was cast aside and Mohammed bin Salman became the crown prince and the first deputy prime minister (the king himself being the prime minister). One can assume that father and son are working in tandem and share the same vision of the kingdom’s future.

The kingdom’s citizens are expected to become less dependent on public-sector jobs and subsidized staple goods.

In April 2016, the crown prince unveiled his ambitious goal – dubbed “Vision 2030” – to diversify the nation’s economy and make it one of the 15 biggest in the world. The plan hinges on drastically reducing the country’s dependence on oil exports. Today, the oil and gas industry accounts for 40 percent of Saudi Arabia’s gross domestic product (GDP), 77 percent to 88 percent of its government revenue and 90 percent of its exports. Under the prince’s vision, Saudi Arabia’s private sector is to become the main growth engine through targeted investments in industry, mining, tourism and entertainment. The government would use the growing tax base to develop its services to the population across the board, from education to health and transportation, as well as to encourage new economic initiatives.

Large-scale projects

The kingdom’s citizens are expected to become less dependent on cushy public-sector jobs and generous subsidies for staple goods. The “National Transformation Project,” adopted by the cabinet in June 2016, includes 80 major projects in priority sectors to be implemented in all the provinces by 2030. Twelve new organizations will be tasked with carrying out and supervising those projects, with many ministries to be reorganized for that purpose. The money for the transformation project is to come from the Saudi Public Investment Fund, to be set up with the proceeds from the sale of a 5 percent stake in the Saudi Arabian Oil Company, Aramco. If the Saudis are correct in their $2 trillion estimate of the company’s market value, some $100 billion can be expected to wind up in the fund.

As a first step, Saudi Arabia is to use the money on acquisitions of high-profile companies around the world. The goal is to increase public revenue and encourage the country’s nascent private sector to enter partnerships with multinationals for developing a sustainable industrial infrastructure in Saudi Arabia. At the “Initiatives for the future” meeting held in Riyadh in October 2017, MbS announced a megacity project called NEOM – a 10,000 square-mile, $500 billion business and industrial zone linked with Egypt and Jordan. In March 2018, Saudi Arabia and Egypt set up a joint $10 billion fund to create an industrial park in the Sinai Peninsula. A bridge over the Gulf of Aqaba is to connect the two countries.

Measured change

On the home front, the prince is following through on the cautious reforms of King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz (2005-2015) who allowed women to vote and run in local elections. The late king also appointed younger officials to oversee education, introduced sports classes for girls in schools and let young men and woman study together in the new science university built in Jeddah.

In a crackdown that stunned the country, 381 of Saudi Arabia’s wealthiest men were jailed.

In his turn, MbS has focused on reducing the prerogatives of Islamic institutions (Friday sermons for the mosques are now written in a government ministry) and further easing the traditional corset of restrictions on Saudi women. The latest reforms allow them to drive cars, attend open-air concerts and sports events, as well as go to cinemas, newly allowed in the kingdom. The crown prince also has intensified the anti-corruption effort.

In a crackdown that stunned the country, 381 of Saudi Arabia’s wealthiest men were jailed in January 2018, including such prominent members of the royal family as Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, owner of the Kingdom Holding Company. The suspects, accused of using bribes and taking advantage of their positions to defraud the state, were detained until most of them paid vast fines – the total sum reportedly reached $100 billion.

Even though these moves by the crown prince antagonized the religious establishment, the more conservative part of the Saudi Arabian society and several members of the royal family, there was no public protest – perhaps in the hope that he would go no further. On the other hand, MbS was applauded in the West and feted by politicians and celebrities during his long roadshow in the United States to promote his vision and attract investment.

Financial means

There is little doubt that the prince’s initiatives stem from his ambitions for the kingdom. The problem, however, is how this grand vision of development is supposed to be financed. Saudi Arabia has had to cope simultaneously with a protracted and significant decrease in oil revenue, a growing budget deficit and the depletion of its foreign reserves. The latter shrank from an August 2014 peak of $737 billion to $488.9 billion by the end of 2017. (They have since risen modestly, thanks to a jump in oil prices in 2018.) Previous attempts at economic reform failed, and the country’s economic growth has slowed to less than 2 percent. According to Saudi Arabia’s General Authority on Statistics, the unemployment rate increased to 13.9 percent in the first half of 2018. For the key 25-29 age group, it exceeded 34 percent. Such trends could lead to growing discontent and instability.

Getting MbS’s reforms off to an auspicious start will hinge, paradoxically, on the country’s oil income levels. The kingdom sits on the world’s second-largest oil reserves, estimated at 267. 9 billion barrels. According to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, it is globally the second oil producer (after the U.S.), with an output of about 10 million barrels a day (mb/d). As the leading player in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the oil producers’ cartel, Saudi Arabia exerts a strong influence on the price of the commodity. However, faced with significantly depressed prices in recent years, it was long unable to enforce an effective policy response.

Facts & figures

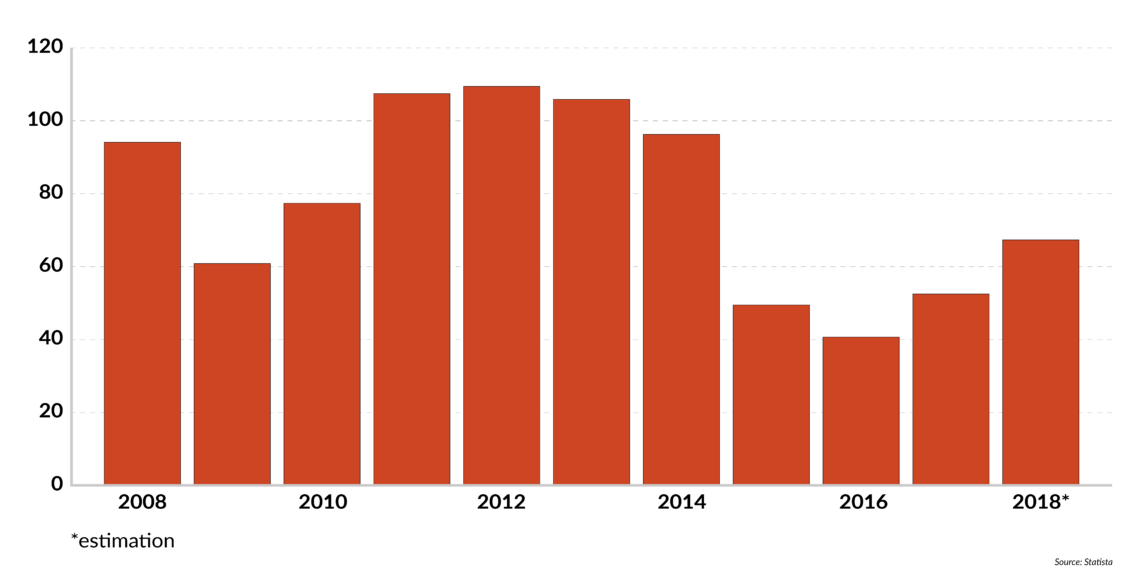

Average annual OPEC crude oil price, 2008-2018

(in U.S. dollars per barrel)

Facts & figures

Breakeven prices

The International Monetary Fund calculates that Saudi Arabia needs oil prices to average $70 per barrel in 2018 for its budget to break even. In 2017, that breakeven price was $73 and in 2016 it was $96.

This compares to the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) estimated breakeven point of between $75 and $80 per barrel in 2018. These figures are high when compared to Kuwait’s $46.50 and Qatar’s $46.80.

In May 2016, Saudi Arabia’s veteran oil minister Ali al-Naimi, who had failed to persuade other key producers to freeze their output to shore up the prices, was fired. With policymaking power concentrated in his hands, MbS reached a deal with Russia to form an alliance between OPEC and non-OPEC producers (known as OPEC+) to try to “rebalance” the market at a higher price than the system could have generated by itself. With an agreement on production quotas finally in place, the strategy succeeded in putting a floor under oil prices. Then they began to creep up.

This allowed Saudi Arabia and Russia to agree at the June 2018 meeting in Vienna to a production increase of 1 mb/d “to avoid world disruption.” At that point, President Trump tweeted that King Salman had agreed to increase his country’s output by 2 mb/d after the new U.S. sanctions against Iran go into effect on November 4. The Saudis admitted that the subject had been discussed but neither confirmed nor denied the U.S. president’s information. The explanation: Saudi Arabia may not be able to ramp up its production by so much so quickly, but Riyadh fears that other OPEC members could use the opportunity to enlarge their shares in the cartel’s output. It may also worry that such a big jump in oil production could depress the commodity’s prices.

Dangers ahead

In any case, Saudi Arabia is positioned to increase its export revenue because of its low oil extraction costs and modern production, transportation and processing facilities. It is not yet clear, however, when and at what price the partial privatization of Aramco will be realized. There is talk of a Chinese conglomerate being ready to purchase the entire 5 percent stake. If that option is chosen, the kingdom will not have to deal with multiple investors and market price fluctuations.

Financing his vision is not the only challenge that the reformist crown prince faces. Getting the socially frozen, religiously fundamentalist kingdom to adapt to modern market economy rules and globalization will not be easy. Attempts to wean the population from subsidies and generous salaries paid by the state, coupled with large-scale layoffs in the oil sector, could spark public unrest. By and large, the Saudi population is not equipped to compete for the new private sector jobs envisioned by MbS or to accept lower incomes. The kingdom may be forced to import large contingents of unskilled workers and highly paid specialists to make its industrialization possible. These burgeoning industries could create a new proletariat, which, in turn, would be prone to unionizing.

The Saudi population is not equipped to compete for the new private sector jobs or to accept lower incomes.

For its part, the royal family is ill-equipped to deal with disobedience of any kind without the use of force. That would frighten investors away and stunt the transformation. However, the crown prince may find allies in young university graduates, who today cannot find work and eagerly await the promised changes.

“Vision 2030” is an attempt at a revolution from above that will nonetheless require consent from both society and the ruling elite to produce the desired results. Winning this approval, in the kingdom’s reality, may prove extraordinarily difficult to achieve.

The project also has significant political implications. In a modern Saudi Arabia with an expanding private sector, the present tribal and patriarchal regime would have to adapt to the appearance of political parties, civil society organizations and, ultimately, parliamentary government and the division of powers. That would mean a constitutional monarchy.

None of this would be acceptable to a royal family reigning by divine right, on the basis of a fundamental law stipulating that only the children and direct descendants of Ibn Saud can rule the realm. The Wahabi religious establishment, too, will not easily relax its hold on the traditionally minded population, which is deeply attached to the royal family.

Having taken steps to grant minor rights to women and curb the powers of the clergy, Crown Prince bin Salman recently declared that he must keep in mind the conservative nature of his country and proceed with care. As recently as June 2018, 17 people were arrested in Saudi Arabia for “crimes against the security of the state.” Among them were at least five women who had agitated for the right to drive – and activists calling for a more moderate Islam. Some have been released pending trial. The prince may be sending a clear signal to his subjects that he does not intend to launch a religious and social revolution – at least for now.

Scenarios

The “Vision 2030” process has barely started; the implementation phase is still to come. What we see now are merely preparations: networking, fundraising and project planning. There is no information on whether MbS has thought through the implications of his design. The first test may come when the Aramco sale goes through – handing the crown prince the means to press ahead.

Meanwhile, there are complex external challenges to be managed. The most dangerous is the Iranian threat, clearly evident in the protracted and costly conflict with the Houthis in Yemen, which has turned into a full-blown proxy war. Then there is the embargo imposed on Qatar by Riyadh and its Emirates allies, Bahrain and Egypt, on the (justified) grounds that the sultanate financed Islamist terror groups and endangered the Gulf’s security. These and other difficulties may also slow the implementation of “Vision 2030.”