Scenarios for the future German government: Part 1

Next month, elections in Germany will determine who will succeed Angela Merkel as the country’s chancellor. A look at the leading parties suggests several coalition possibilities – and even a “Jamaica” combination could be in the cards.

In a nutshell

- The CDU/CSU looks set to win September’s elections

- The Greens will likely come in second and join the coalition

- Armin Laschet will probably become the next chancellor

Germany elects a new federal parliament on September 26, 2021. The 20th Bundestag since 1949 will choose a new chancellor as soon as a coalition government secures a majority. This time, however, there will be a momentous change: that chancellor will not be Angela Merkel. After 16 years leading the government and 31 years as a member of the Bundestag, she will retire from politics, not even running to keep her seat in the legislature.

Who is most likely to take her place? Plenty can still happen, since the election campaign will only start in earnest toward the end of August when citizens return from their summer holidays. Still, there are already some strong trends that allow us to make some predictions.

Who will win?

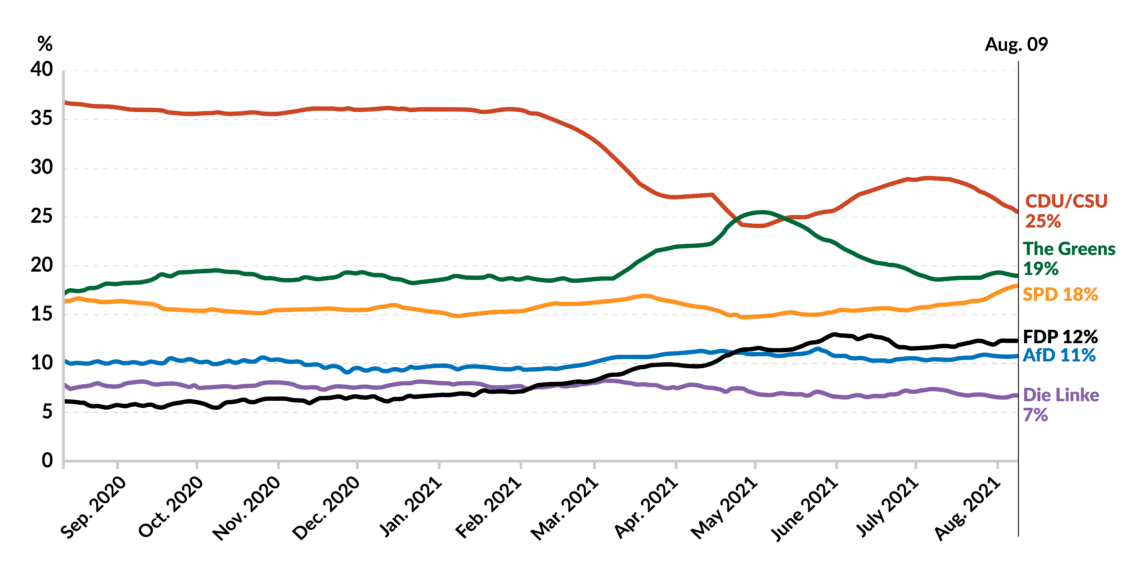

A look at the “poll of polls” over the last 12 months reveals that the center-right Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) are highly likely to win a plurality of seats and that they are therefore most likely to get their candidate, Armin Laschet, into the chancellery. There was only one brief period in early May, just after both the Green party and the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) announced their top candidates, when it looked like the Greens could overtake the Christian Democrats and make their co-chair, Annalena Baerbock, the new chancellor. At the time, Ms. Baerbock received a lot of media attention (especially from public outlets). On the other hand, Armin Laschet, governor of the most populous German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, was portrayed as a potentially weaker candidate than his CSU rival for the head of the CDU/CSU political family, Bavarian Minister-President Markus Soder.

The Christian Democrats are likely to win and make their candidate, Armin Laschet, the chancellor.

Public opinion has shifted since then, restoring a somewhat comfortable 10 percentage-point lead for the Christian Democrats over the Greens (which has recently shrunk slightly to six points). Later in May, it was revealed that Ms. Baerbock neglected to declare ancillary income, that she embellished her resume, and that a book published under her name (it was mostly ghostwritten) included several plagiarized passages. All this eroded trust in the Greens’ candidate and reminded some that besides a few years of party management, Ms. Baerbock has little executive experience.

Coalition on the way

Politics in Germany, like elsewhere, has become focused on individual politicians. Nevertheless, the country’s general elections are all about the parties. Citizens do not directly elect the head of the federal government or their state. Instead, candidates backed by a majority of representatives in their various legislatures take those positions. As has been the case throughout almost all of Germany’s postwar history, it is clear that the new government will be a coalition.

The CDU and the Greens have already formed well-functioning coalition governments in two states.

When analyzing the plausible party combinations, one can definitively discard the Alternative for Germany (AfD). This far-right, populist party has had considerable success in recent federal and state elections, mainly in the east of the country. All of the other parties have ruled out the AfD as a coalition partner.

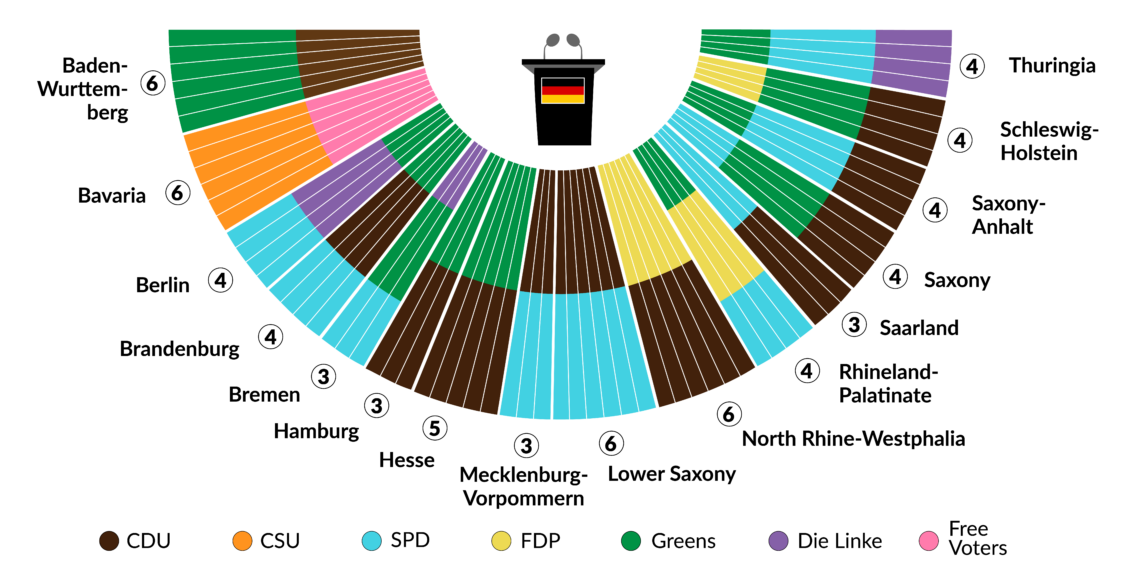

The same is not quite true of far-left party Die Linke. It still leads a minority government with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and Greens in Thuringia and is a member of governing coalitions in the traditionally left-wing city-states of Berlin and Bremen. The chart below illustrates just how versatile German coalition forming can be.

Facts & figures

As things stand, there are only two ways to form a government without the CDU/CSU. One would be for the Green party to build a coalition with the SPD and Die Linke. However, the numbers are unlikely to add up after the September elections (though they almost did in some polls in early May this year). Even if they do, the postcommunist Die Linke, with its radical new leadership, is considered unsuitable to govern on a federal level even by officials from the SPD and Greens. The party does not subscribe to basic elements of German politics, such as a private property-based market economy or membership in NATO and the European Union.

The second option would be for the Greens to put together a “traffic light” (green-red-yellow) coalition with the SPD (party color – red) and the Free Democrats (FDP, party color – yellow). This combination of colors also occurs at the state level – in Rhineland-Palatine, under SPD leadership. But even if it became likely that all three of these parties together will win a majority of seats, it is unlikely to form. The FDP would be loath to enter such a coalition under a Green Chancellor, as the party’s leaders have repeatedly made clear.

There is a similarly low-probability scenario (less than 10 percent) in which the CDU/CSU (traditionally represented by the color black) and the FDP form a coalition. Both parties are close in terms of economic and foreign policy, and they have formed a well-functioning coalition in North Rhine-Westphalia under Mr. Laschet. However, these two parties together will probably not have a majority.

Heading toward Jamaica

That leaves the Green party as the kingmaker under a (most likely) CDU/CSU-led government coalition. No matter who finishes first, it will be almost impossible to build a coalition without it. Two decades ago, a coalition between the Greens, who at the time were rather fundamentalist, and the CDU/CSU, which was more conservative than it is now, would have seemed preposterous. Today, it is the preferred combination by many in the Angela Merkel- and Armin-Laschet-led CDU, which has taken a turn toward the left/green side of the political spectrum. The Green party has also become much more centrist and realist in recent years. The parties have already formed well-functioning coalition governments in two populous and prosperous states: in Hesse under CDU leadership, and in Baden-Wurttemberg under the leadership of the Greens.

Mr. Laschet may have won the candidacy because of his ability to rally his troops within the party.

The only remaining question is whether these two parties will need a third partner to build a majority. In that case, Mr. Laschet and Ms. Baerbock would have a choice between the FDP and the SPD. Mr. Laschet would prefer the FDP, and Ms. Baerbock the SPD. Yet the SPD is far less willing than the FDP to enter such a coalition. For the former, to once more serve under a CDU chancellor as a junior partner – even taking third place behind the Greens – would be another humiliation that its declining and increasingly angry membership would be unlikely to accept.

For the FDP, however, entering a black-green-yellow coalition (like the one that governs in Schleswig-Holstein) would now be accepted as a step forward. This option – known as “Jamaica” because the parties’ colors are those of that country’s flag – was on the table after the last federal elections in 2017. In the end, the liberal democrats pulled out because Chancellor Merkel’s CDU/CSU negotiators were prioritizing the Greens’ demands over the FDP’s. This time, the liberals can expect Armin Laschet to be more open to cooperation. Moreover, their refusal to enter the 2017 government greatly frustrated their voters – they will not risk disappointing them again.

In summary, it is likely that Armin Laschet (CDU) will become next chancellor of Germany after the elections this September. It is equally likely that the Green party will become a major part of the next German government. It is possible that the liberal FDP will also join the government coalition. At this stage, one can safely ignore the policy proposals put forth by the AfD and Die Linke, but also probably the SPD, though the share of the vote they receive will certainly affect the difficulty of the CDU/CSU’s coming task of forming a government.

Who is Armin Laschet?

Armin Laschet is 60 years old. The son of a coal mine engineer, his family is originally from Liege, Belgium, and he speaks fluent French. He earned a law degree and worked as a journalist for a Catholic newspaper before his political career. In 1994 he was elected to the German Bundestag and in 1999 he became a Member of the European Parliament. In 2005 he entered state politics in North Rhine-Westphalia, becoming state minister for Generations, Family, Women and Integration, and later for Federal Affairs, Europe and Media. In 2017 he won the election to become minister-president of the state, which for most of its history had been run by social democrats.

In January this year, Mr. Laschet won an open membership contest to become CDU party leader, overcoming two candidates who were popular within parts of the party because of their trustworthiness and foreign policy expertise (Norbert Rottgen) or for their conservative-liberal credentials and charisma (Friedrich Merz). Mr. Laschet may have won because of his ability to rally his troops within the party as leader of the most powerful state constituency, his support for Angela Merkel in challenging times (such as the refugee crisis), and his talent for bringing various factions within the party together as a centrist conciliator.

Many observers find him too soft, too uncommitted and too jovial. Some even ridicule him for his occasional clumsiness and portray him as unfit for the job of German chancellor. Then again, many felt the same way 16 years ago about CDU’s party leader at the time, Angela Merkel.

In part 2 we will look at what changes an Armin Laschet-led CDU/CSU-Green government coalition (possibly with the addition of the FDP) could implement.