More power to eurozone governments

The sovereign debt crisis prompted a raft of new EU regulations overseeing member states’ fiscal and budgeting processes. At first, the rules gave a lot of power to the European Commission, but eurozone governments now tend to use the coordination process to place themselves above the Commission and the peripheral member states.

In a nutshell

- The euro crisis prompted stricter EU rules for member states’ finances

- Initially, this gave the European Commission much more power

- Eurozone governments are now taking the more prominent role

- There is still no robust institutional EU backup against debt spillover

It is often argued that the sovereign debt crisis was a turning point in European Union governance. At its peak in 2009-2011, the crisis threatened to disintegrate the euro area and imperil the still young common currency. Several eurozone countries (with Greece at the top of the list), after accumulating huge, unsustainable deficits, even found themselves to varying degrees in danger of a possible default.

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which was enacted in 1997 and limited government budget deficits to 3 percent and public debt levels to 60 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), had obviously failed to secure fiscal discipline in the EU. Also, there seemed to be no effective means in place to prevent debt contagion from the overindebted peripheral countries to the bigger economies of the Union.

The European Semester (ES) is one of the numerous crisis-inspired emergency measures introduced in 2010 to strengthen the SGP. While the SGP’s thresholds were maintained, the ES was soon completed by two, ostensibly more constraining, legislative packages known as the Six-Pack (2011) and Two-Pack (2013). These, together with the Fiscal Compact (2012), were supposed to create a rigorous and politically binding postcrisis framework. The Six-Pack put forward a tool that was to become a crucial pillar of the ES: the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP), which aims to prevent and correct precisely those types of imbalances that had provoked the euro crisis.

Tighter surveillance

Simply stated, the ES is an annual cycle for policy coordination across EU countries. The purpose is to place member states’ fiscal, budgetary and macroeconomic policies under close surveillance by the European Commission and the Council of the EU, to make them comply with the EU’s targets.

What is noteworthy in this process is the limited role assigned to national parliaments.

The ES gives governments a strict timeline. In October, the first national draft budgetary plans for the following year must be submitted to the Commission. In November, the latter reveals the Union’s fiscal goals and political priorities in an Annual Growth Survey (AGS). It also releases an Alert Mechanism Report (AMR), which designates the “black sheep” among countries eligible for an evaluation under the MIP.

In February, the Commission issues a Country Report for each member state, assessing the progress that has been made in terms of structural reform. Countries belonging to the risk group will furthermore receive an In-Depth Review, which examines the nature and severity of their macroeconomic imbalances.

By the end of April, member states must tell the Commission the budgetary measures they intend to implement to fulfill their SGP commitments. At the same time, each government is required to detail its ongoing reform agenda. After examining these medium-term fiscal plans, the Commission publishes revised Country-Specific Recommendations (CSRs) in May, which are finally adopted by the Council in July. Governments are then supposed to include them in their budgets for the upcoming year. What is noteworthy in this process is the limited role assigned to national parliaments.

(Un)expected winner

The reality behind this intricately timed surveillance framework is more complex than it appears at first sight. The Semester is designed as a hybrid that seeks to reconcile “intergovernmental” (bottom-up) cooperation methods with “supranational” (top-down) intervention mechanisms – and the balance is constantly disputed.

On one hand, the ES presents itself as a tool for collective learning, multilateral surveillance and peer review, enabling member states to discuss each other’s budgetary plans early on and to “monitor progress collectively”; on the other, it places member countries’ annual budgets under strict supervision by European institutions endowed with real sanctioning capacities.

To make sure that national governments pursue sound public finances, the Commission has seen its discretionary powers significantly increase. As happens with many EU institutions, the ES rapidly developed a byzantine governance architecture, with the Commission at its heart. This evolution has prompted observers to describe the Commission as the “unexpected winner” of the euro crisis, as its involvement in practically every aspect of EU governance has expanded significantly since 2010.

Facts & figures

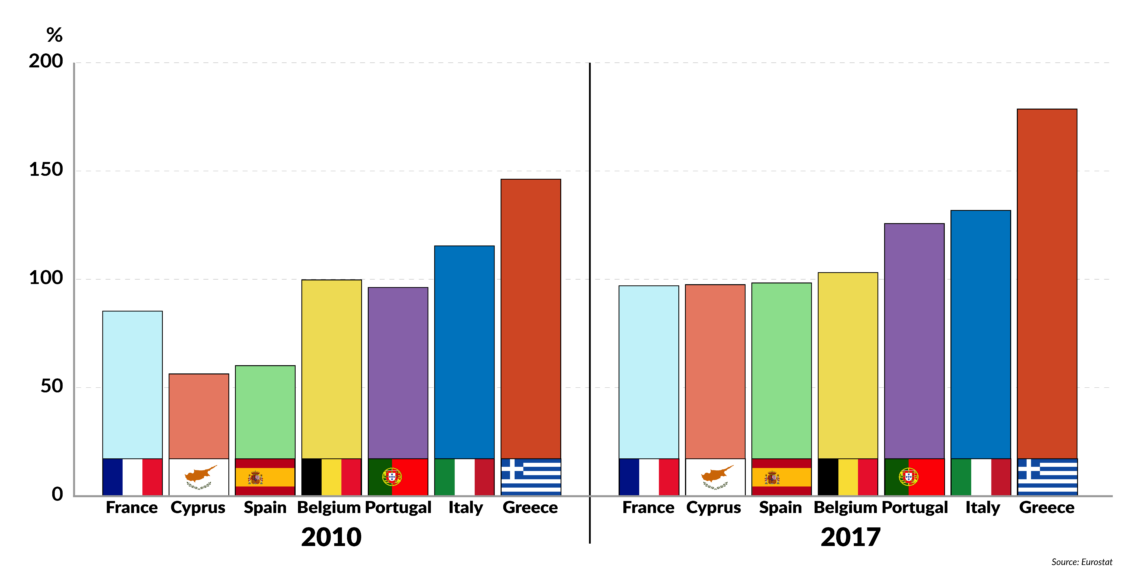

Government debt-to-GDP ratio

Selected EU member states, 2010 vs. 2017

This was particularly true in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, when the Commission (as part of the Troika) imposed, mainly through the threat of sanctions, fiscal consolidation and budgetary austerity on member states. Preventing excessive macroeconomic imbalances in the EU was the Commission’s top priority in the early ES cycles, along the motto that problems must be contained before they spread.

Several eurozone countries thus received formal warnings in their CSRs, since they were not able to meet the requirements of the SGP. At that time, some were caught in a dilemma: either they complied with the SGP, thereby losing even more growth and jobs in their already severely stressed economies; or they decided to breach the SGP’s thresholds to provide some oxygen in the form of growth-oriented policies. But then, in addition to being named and shamed, they would be liable to face an Excessive Imbalance Procedure or an Excessive Deficit Procedure under the ES, with potential financial sanctions in case of noncompliance with the Commission’s injunctions.

Quiet expansion

It did not take very long before the colossal damage inflicted by the Troika’s austerity measures on the populations of several eurozone countries (Greece, again, at the head of the line) was plain to see. That story is well-known. What is less obvious is the subsequent evolution of the Commission’s role in EU economic governance, once the rhetoric of budgetary rigor was ratcheted down.

In recent years, the Semesters increasingly build on “socially balanced” (critics might say, diluted) objectives, supposed to adhere simultaneously with the SGP, the Fiscal Compact, the Integrated Economic and Employment Policy Guidelines, and the far more “social” and “green” Europe 2020 Strategy. A new, wide-ranging “social scoreboard” has significantly watered down the standard headline indicators of the initial ES framework, which covered typically fiscal issues such as budget imbalances or debt.

After the Juncker Commission took office in late 2014, growth, investment and jobs have become the Union’s new priorities (set out in the post-2015 Annual Growth Surveys), and austerity is clearly banned from the “revamped” ES vocabulary. This U-turn coincides with the ambitious 500-billion-euro Investment Plan for Europe (the so-called Juncker Plan) and the European Central Bank’s continuing ultra-loose monetary policy under President Mario Draghi. Since early 2015, the ECB has pumped trillions of euros into the European economy, triggering a miraculous recovery. For its part, the Commission not only substantially eased up on the SGP rules; in 2016, it started to call for a fiscal expansion of 0.5 percent of GDP per year, saying the stimulus was indispensable to foster investment, employment and growth.

Germany’s annoying surplus

Under the new, moderated ES paradigm, economies that run smoothly, with no public deficit, low public spending levels and, as in the case of Germany, significant budget and trade surpluses, are viewed with a suspicious eye. A model pupil during the austerity era, Germany is suddenly considered to be deviating from the SGP rules. According to the Commission, Europe’s biggest economy is saving too much. It should spend much more, especially by investing in infrastructure, thus favoring growth in the whole EU.

While some countries are pressured to offset their budget deficits, others repeatedly obtain leeway.

For former German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schauble, this argumentation is absurd and counterproductive. Above all, it reflects the wrong priorities. Germany is plainly unwilling to play the Commission’s new game.

‘Because it’s France’

The Commission has also been accused (by Germany, among others) of being too lenient or biased, because it does not apply the same rules to all. While some countries continue to be pressured to adopt fiscal measures to offset their budget deficits, others repeatedly obtain leeway.

When asked why the Commission turned a blind eye to France’s systematic noncompliance with the SGP rules for several years, Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker bluntly declared on French television: “Because it’s France.” This remark has certainly not bolstered the Commission’s credibility as an objective promoter of sound public finances and fiscal stability in Europe.

Self-serving coordination

What the Commission’s smooth talk in the recent AGRs, CSRs and other technocratic reports may reflect above all is a certain disempowerment of the EU’s executive arm in favor of the core eurozone governments. More and more, the latter tend to use the intergovernmental coordination process to place themselves above the Commission and the peripheral member states, pushing them to adopt cutbacks and structural reforms they are not willing to do themselves. With French President Emmanuel Macron and the support of European Economic and Financial Affairs Commissioner Pierre Moscovici, France has become a powerful player in the current EU intergovernmental game.

In turn, smaller countries, though compliant at the surface, often are just “cherry-picking” from the policy recommendations that suit their interests, especially if their governments are subject to diverse EU governance frameworks, such as the European Semester, Balance-of-Payments Programme and Maastricht Convergence criteria.

Low impact

Concerning the implementation of the ES, strangely, there is no consensus among analysts and policymakers. While the Commission claims that 80 percent of the CSRs have been adopted, external observers tend to say it is more like 10 to 20 percent. According to the Brussels-based economic think tank Bruegel, the implementation index has steadily fallen since the inception of the ES and is lower than the implementation rate of the OECD’s unilateral recommendations.

The Commission is ceding further ground not only to strong EU member states, but also to its institutional rivals.

Despite innumerable warning letters and lengthy reports circulating between the Commission and member states during the ES cycles, no country (including those under MIP) has so far been sanctioned for not complying with the SGP’s fiscal rules, except in the case of proven statistical fraud. This happened only once, in 2015, when the Commission recommended slapping a fine of 19 million euros on Spain, after the region of Valencia misreported deficit data. As for the other components of the ES framework, such as the Employment Policy Guidelines or the Europe 2020 Strategy, it is virtually impossible for the Commission to impose formal sanctions on noncompliant governments.

Moment of truth

It therefore seems that the Juncker Commission, instead of accumulating power, is ceding ground to the stronger EU member states and to institutional rivals such as Mr. Draghi’s ECB.

The question is whether the postcrisis “architecture of EU socioeconomic governance” embodied by the ES can prevent another sovereign debt crisis from erupting in the years to come.

Recent statistics concerning the debt-to-GDP ratios of several euro-area countries reveal a worrisome reality. Between the euro crisis and today, the debt ratio has risen to alarming levels for Belgium (from 99.7 in 2010 to 103.1 percent in 2017), Spain (from 60.1 to 98.3 percent), France (from 85.3 to 97 percent) and Italy (from 115.4 to 131.8 percent). Unsurprisingly, despite years of effort, Greece’s debt level (rising from 146.2 percent to 178.6 percent) remains on an “explosive path,” as the International Monetary Fund has warned.

A fateful moment will come when Mr. Draghi’s expansionary monetary policy comes to an end, confronting these countries not only with the reality of their huge debt, but, more importantly, with their limited capacity to spur sustainable growth without a generous oxygen supply from the ECB. For the moment, the ECB is already reducing its monthly pace of bond buying; the tap should be fully closed by 2019.

If some member states run into trouble (Italy and Greece come to mind), they might pull down other members of the eurozone, if not the entire currency bloc. The only way to avoid this nightmare scenario is to set up a truly effective institutional backstop to protect the Union against the spillover and domino effects of a renewed public debt crisis. Time is running out for this to happen.