Uruguay’s uncommon strengths and dilemmas

Uruguay scores perfect tens on civil liberties and the electoral process in the World Bank’s rule of law index – matching Norway and New Zealand. The country’s internal stability is buttressed by an ambitious social welfare system.

In a nutshell

- Uruguay is a model democracy and highly developed society with ambitions to play an international role

- To afford its storied social safety net and transparent institutions in the future, it must reinvent its economy

- The country’s ruling progressives seem unsure how to meet multiplying economic and social challenges

Just over a hundred years ago, and not quite a century after the country had won its independence from Spain and disentangled itself from its larger neighbors Argentina and Brazil, Jose Batlle y Ordonez, the 19th and 21st President of Uruguay (1903-1907; 1911-1915) set out to establish a social welfare system that would make his country “the Switzerland of Latin America.”

For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, Uruguay struggled in its role as a buffer between Argentina and Brazil. Today, Uruguay is reaching for increasing agency in the global community. Its authority stems from the soft power foundation of its social welfare state (now fraying), the strength of its democratic institutions and its remarkable stability. Uruguay scores perfect tens on the indices of civil liberties and electoral process, matched only by Norway and New Zealand, in the rule of law index of the World Bank. It ranks just below Chile in Latin America, far above much larger countries in the region. How it capitalizes on these strengths in the hemisphere and the global arena will depend on its internal stability and the capacity of its leaders to reform the economy.

Signs of change

For the past 13 years, the country has been ruled by a coalition of progressive parties known as the Broad Front (FA in its Spanish acronym). The last three governments have been led by Tabare Vazquez (2005-2010), Jose Mujica (2010-2015) and Tabare Vazquez again (from 2015). The FA has kept a majority in the legislature during this entire period. However, even if the coalition wins the presidency again in November 2019, it appears virtually impossible to keep that majority in the legislature. This murky political situation is only one factor casting doubt on Uruguay’s future stability.

Uruguay’s Gini index of less than 0.4 is the lowest in Latin America, the poverty index dipped below 8 percent in 2017.

Uruguay is the most socially advanced country in the region. It legalized divorce more than a century ago, approved women’s right to vote in 1927, legalized abortion in 2012, and legalized the use of marijuana in 2015. It is profoundly secular in a region where religion, mainly Catholicism and Evangelical Protestantism, are significant factors. This broad national consensus on tolerance and inclusion goes along with a strong inclination toward equality. Uruguay’s Gini index (which measures to what extent the distribution of income or consumption expenditure among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution) of less than 0.4 is the lowest in Latin America, while the poverty index dipped below 8 percent in 2017.

On top of this, Uruguay has enjoyed more than 10 years of uninterrupted economic expansion since the severe recession of 1999-2004. While the growth rate has come down from its peak during the commodities boom earlier in the decade, the economy has continued expanding, even if at more modest rates of between 2.5 and 4 percent.

Facts & figures

Uruguay, vital facts and data

- Montevideo was founded by the Spanish in 1726 as a military post. Claimed by Argentina and annexed at first by Brazil, Uruguay declared its independence in 1825 and secured its freedom after a three-year armed struggle

- Official language: Spanish

- Government type: presidential republic

- Parliament: bicameral General Assembly

- Legal system: civil law system based on the Spanish civil code

- Total area: 176,215 square km

- Population: 3,360,148 (2017 est.)

- Climate: warm temperate

- Natural resources: arable land, hydropower, minor minerals, fish

- Population distribution: most of the country's residents dwell in the southern half of the country; approximately 80% of the populace is urban; nearly half of the population lives in and around the capital of Montevideo

- Ethnic groups: white 87.7%, black 4.6%, indigenous 2.4%, other 0.3%, unspecified 5%

- Economy: a free market economy characterized by an export-oriented agricultural sector

- Agriculture products: cellulose, beef, soybeans, rice, wheat; dairy products; fish; lumber, tobacco, wine

- Industries: food processing, electrical machinery, transportation equipment, petroleum products, textiles, chemicals, beverages

- GDP (official exchange rate): $58.42 billion (2017)

- GDP per capita (PPP): $22,400 (2017)

- GDP real growth rate:

- 2017: 3.1%

- 2016: 1.5%

- 2015: 0.4%

- Employment: agriculture 13%, industry 14%, services 73%

- Public debt as % of GDP:

- 2017: 66.2

- 2016: 61.9

The downside

Despite these achievements, Uruguay is no Panglossian paradise. As the next presidential election in 2019 nears, the country is going through a period of national doubt. Part of it is political: sitting President Vazquez is ineligible to run due to constitutional term limits; his predecessor Mr. Mujica, who is 83, will not run for president again; and the Broad Front is showing signs of internal tension.

While Uruguay continues to grow and the indicators of social welfare still look good, its economy needs to become much more competitive and diversified if it is to sustain in the future the cherished social welfare net. But how the arteriosclerotic state can be modernized without causing a social upheaval that could undo all the progress of the past decades – this remains an open question.

The Broad Front began as an alliance of left-of-center political movements, some of which were markedly more radical than those usually associated with European social democrats. After FA’s 13 years in power, the pragmatists have become stagnant and the radicals appear to have recovered their ideological fervor. Right now, the Front seems certain to fragment going into the new elections.

The opposition, which consists of the two traditional parties, the Blancos and the Colorados, has been trying to forge a united coalition against the FA. The Blanco-Colorado coalition’s problem is that it cannot afford to appear as a “conservative” alternative to the FA. An overwhelming majority of the Uruguayan voters want to keep the welfare state, so the challenge for the opposition is to conceive a program that would make it more efficient and fairer.

Search for strategy

If stability and steadfast adherence to the rule of law is the foundation of Uruguay’s international relevance, its future role will hinge on whether the country can break through the middle-income trap and start competing at the high-income level of the global economic game. What strategy could make such a transformation possible?

There was never an option to attract capital through low wages as the Asian Tigers did. It is also not clear how Uruguay can become a center for innovation, like Israel or Taiwan, because the country’s underperforming educational system is one of its critical weaknesses. The FA has done little to improve the system during its years in government.

Uruguay’s economy got a massive boost from the Chinese-demand-driven export boom, which made governing easier during the FA’s first two administrations. In retrospect, however, it is clear that while the country’s beef producers improved their product to international standards and the farmers increased their crop output (especially of soybeans, for which the global demand appears insatiable), the state has done little to help boost productivity. Instead, it raised taxes on agricultural production.

The main barrier to greater competitiveness is an inefficient state, which demands an ever-higher share of the profits while offering, in exchange, costly and low-quality public services. This is not a sustainable setup.

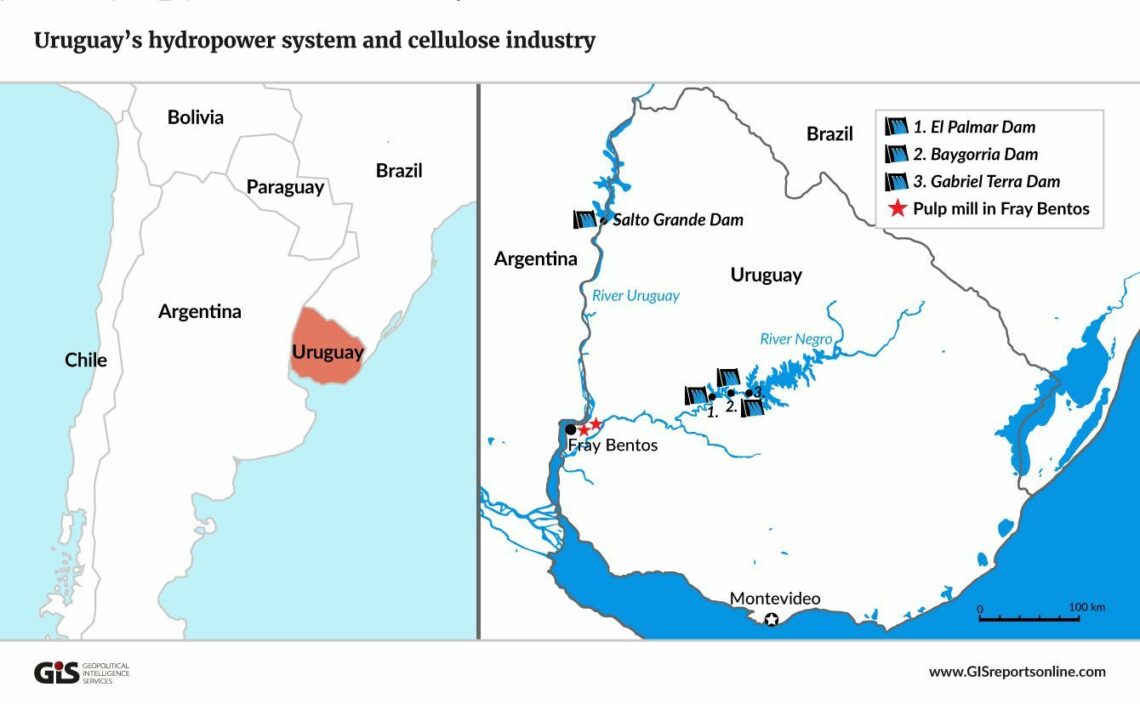

One intriguing initiative of the FA governments has been the construction of large paper pulp mills along the country’s western riverine boundary, taking advantage of the hydropower of the Uruguay and Negro Rivers. Two of these plants were built with foreign capital (from Finnish, Swedish and Chilean investors) and more are planned in the future. The paper pulp facilities have caused a protracted political conflict with Argentina and considerable outrage among local conservationists, not to mention internal political disputes over concessions granted to the investors by the government.

Banking is another area where Uruguay might play a bigger regional role, since adherence to the rule of law is a strong consideration in the financial sector. Given the fragility of the Brazilian and Argentine currencies, not to mention their legal systems, Uruguay’s banks have been a haven between the two larger, unstable economies since the middle of the last century. Now, this system could be upgraded to meet the demands of the global economy. This would require Uruguay to craft regulations to attract the capital and technology necessary to create a regional banking services and data center. The emerging conservative coalition has made this goal one of its campaign planks.

Uruguayans had to pay more for gasoline and electricity than citizens of any other country in the hemisphere.

Another FA success over the past decade has been a reduction in Uruguay’s total dependence on imported energy. The country lacks domestic fossil fuel deposits, which stunted its economic development over the past century. It needed to import energy and pay international prices for it. The National Administration of Fuels, Alcohol and Portland Cement (ANCAP), an entrenched monopoly created by the government in 1931 to deal with the energy challenge, only made things worse. For decades, Uruguayans had to pay more for gasoline and electricity than citizens of any other country in the hemisphere. The ANCAP became a symbol of inefficiency and corruption. In 2015, a scandal linked to the company’s disastrous management practices led to the resignation of Vice President Raul Sendic, elected with Tabare Vazquez.

For the past decade, however, Uruguay has been investing heavily in renewable energy technologies such as wind and solar. In 2017, the country generated 33 percent of its electricity from renewables, up from 1 percent in 2013. The goal is to reach the 50 percent mark early in the next decade.

Facts & figures

Crime scare

Two social issues will complicate Uruguay’s domestic politics over the next year.

The most significant is the growing perception among Uruguayans that crime and violence have increased in recent years and that citizens are less safe today than they were in the past. There is evidence that violent crime has grown over the past decade in Uruguay – but from levels that are extremely low by Latin American standards.

At the beginning of the century, the homicide rate in Uruguay fluctuated between 5 and 6 per 100,000 population. It rose to 7.8 in 2012, peaked at 8.5 in 2015 and settled back to 8.1 in 2017.

This upsurge in the murder rate is significant politically because the FA claimed it was caused by globalization and the neoliberal economic policies of predecessor governments (1985-2005), which caused economic and social distress. Its policy response was to support the most vulnerable in the society, reduce poverty and retain as many social programs as possible. Elsewhere in Latin America, the same social malaise was treated with an entirely different set of policies – mano dura (hard hand), zero tolerance, harsh policing etc. – with similarly disappointing results.

Racism’s lingering effects make the leftist coalition’s policies of social inclusion look ineffectual.

The FA created a trap for itself on crime by failing to improve or modernize the police and other law enforcement agencies. Given that its social policies have indeed reduced poverty and indigence, it has become harder for the government to attribute rising crime to destitution.

When the data are disaggregated, it emerges that the rising homicide rate is more closely linked to the presence of organized international crime than anything else. Crimes related to the drug trade are playing a growing role in the violence. An effective response, as other countries in the region have discovered, requires increasing the sophistication and professionalism of the national police forces.

The race issue

The other social problem undermining the FA’s political standing is the persistent racism in the country, especially in Montevideo. Its lingering effects make the leftist coalition’s policies of social inclusion look ineffectual. An estimated 10 percent of the population is of African descent, and Uruguayans’ traditional tolerance of sexual and gender minorities often does not extend to their fellow-citizens of color. However, almost all countries in Latin America have issues with race – African or indigenous. Ironically or not, states that attempt to deal seriously with social inclusion, such as Uruguay and Colombia, are the ones in which racism has become a matter of public debate.

Scenarios

Uruguay is a middle-income country with a welfare state that, at least in its concept and aspirations, mimics those in more developed countries. Its financial cost– as measured by the total tax burden on the population as a percentage of gross domestic product – is 43 percent and approaches that of Finland (47 percent). At the same time, the social benefits in Uruguay roughly match those in Costa Rica, where the tax burden of the state is 29 percent of GDP.

This challenge is exacerbated by an aging population. Uruguay’s demographic pyramid is similar to Italy’s or Spain’s, while the country’s economic productivity is on par with Costa Rica or Panama.

These economic ratios, combined with unfavorable demographic and social trends, form a setup that Uruguay cannot sustain beyond the very short term.

The most likely scenario is that the FA will win the presidency in the next election and muddle through the next government, without a majority in the general assembly. At most, the pragmatists in the FA may join forces with the technocrats of the conservative coalition to offer some timid reforms of the education system, and perhaps make a modest start on curbing public spending. That also means that the new government will take a more cautious approach to world affairs.

A less likely scenario is one in which a conservative parliamentary majority decides to tackle the structural imbalance between public spending and the economic rent produced by the economy. However, making rapid, significant fiscal cuts is a political impossibility in Uruguay.

One proposal being considered by the conservatives would take advantage of the substantial human capital (education level, experience) in the retired population. If those 65 or older and in good health were to take part-time jobs, the reasoning goes, the currently crushing burden of pension spending would be reduced. Other proposals involve a devaluation of the Uruguayan peso to attract the capital necessary to pay for the next stage in the country’s economic development.