The lessons from the last 100 years of Central Europe’s history

The emergence of new nation-states from World War I was hailed as a triumph for self-determination, but the destruction of democratic empires that held them previously hardly brought peace and prosperity to the continent, especially Central Europe.

In a nutshell

- The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 100 years ago left defenceless Central Europe’s smaller nations

- Nationalist sentiments triumphed in 1918 but statehood for smaller entities does not necessarily bring them security or full sovereignty

- To prosper in the European Union, Central European countries need to cooperate closely, such as in the Visegrad Group

November 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I, a tragic and useless European civil war fought around the globe. Without real interest or ideological differences, major European nations sleepwalked into that war. All of them, except for Russia, were democracies. (Propaganda from the countries that emerged “victorious” from the war pretended otherwise, but in fact, also Germany and Austria-Hungary were democracies.)

The madness continued for four years in the battlefields, during which only two peace initiatives emerged. Both had no effect because all the sides involved felt the pressure to bring a full victory home. Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) tried to mediate in 1917, but his plan was widely rejected – except for Emperor Charles I of Austria (1916-1918). In the same year, Emperor Charles entered discreet negotiations with France but was betrayed by his own foreign minister and the initiative failed. The acrimony that followed, unfortunately, limited the Emperor’s room for further actions. Despite his young age, he had broader political, economic and social views than all his counterparts, the leading personalities in Germany, Britain, France, Russia and Italy. He also had a much higher sense of personal responsibility.

Empire’s end

Given the prevailing mindset of the time, it required plenty of courage from the Emperor to promote peace instead of victory. He was able to foresee the catastrophic consequences of this useless bloodshed for all of Europe, but especially Central Europe. He knew full well what the dissolution of his “Danubian Monarchy” would mean to the smaller nations of this area: they all would be crushed between Russia and Germany.

During the war, one of the main objectives of the Entente Powers (an alliance between Britain, France and Russia, joined in 1915 by Italy), pursued by French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1917-1920), the Italian leadership and, later, also by the British cabinet, was the destruction of the Habsburgs’ supranational and federalized Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Britain and France felt victorious, not realizing that they, too, were to lose their empires.

This war was the first of Europe’s bloodiest spasms during the 20th century and marked the rise of totalitarian movements, communism and fascism. After it ended on November 11, 1918, the arrangements for peace laid the foundations for World War II and the (continuing) conflicts in the Middle East and the Balkans. Britain and France felt victorious, not realizing that they, too, were to lose their empires as a result of the war. In Russia, the inhuman and aggressive Soviet imperial system was established, aiming to start a world revolution. The Ottoman Empire, in turn, was filleted by the victors most irresponsibly.

That junction also marked the start of Central Europe’s troubles.

A slew of new nation-states was created in the fall of 1918 in the region. Reconstituted Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Austria and Yugoslavia emerged as newly independent nations. Romania received a large chunk of territory from former Hungary. Now, a hundred years later, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are celebrating their independence, Austria commemorates the end of the 800 years of Habsburg rule, Hungary remembers the loss of two-thirds of its former territory and Yugoslavia does not exist anymore.

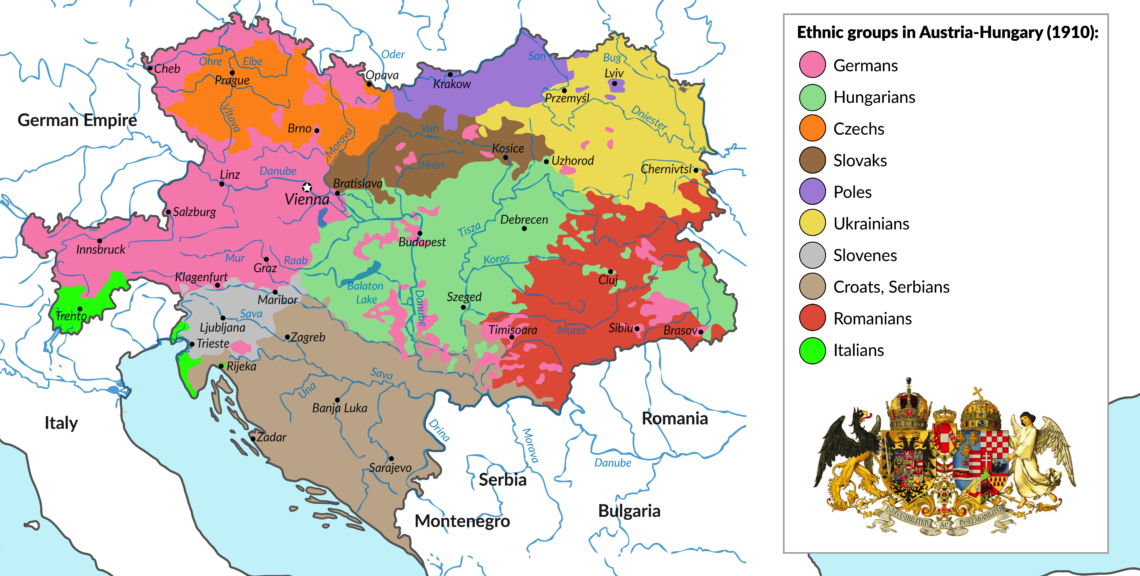

The victorious powers hailed the dissolution of the multilingual Austro-Hungarian monarchy under the pretext that it had been a dungeon for nations – a claim that ignored the monarchy’s federal character. But what happened in reality? Ethnic groups became mixed up in many areas. In Czechoslovakia, for example, Hungarian- and, especially, large German-speaking populations were discriminated against. Italy annexed the German-speaking South Tyrol and some Slovenian areas, mistreating the local populations very badly. And Yugoslavia was an artificial creation, a real political Frankenstein forcing Croatians and Slovenians, both Catholic nations, and Islamic Bosnians into a state dominated by Orthodox Serbs. That creation disintegrated violently, among great bloodshed, some 70 years later.

The so-called “liberation” from the Habsburg Empire meant serfdom for many minorities in the new nations, and most of the new states quickly turned into dictatorships.

In the second decade after the end of WWI, the Soviet Union recovered from the internal turmoil that followed the collapse of czarist rule and Germany had recovered from its defeat. Adolf Hitler (1934-1945) took full power as the leader (fuehrer) and chancellor of the Reich.

Central Europe was up for grabs.

More destruction

The first to lose out was Austria. The country was badly battered after WWI and restricted by the victors who did not allow it, among others, to have strong artillery or an air force. Germany imposed economic sanctions against it and Vienna constantly heard threats of military intervention by Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, backed by the Western powers if Austria would try to rearm. Small wonder that the country with a weak army and a population living in poverty was such an easy grab for Hitler’s Third Reich in March 1938. Austria’s pleas in London and Paris for protection, by then-Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg (1934-1938) and the young Archduke Otto (1912-2011), the former Habsburg crown prince in exile, were cynically turned down.

Czechoslovakia’s sorry fate was sealed by the betrayal by Britain and France.

The only country protesting in the League of Nations was Mexico. Czechoslovakia’s President Edvard Benes (1935-1938 and 1945-1948) hailed Austria’s annexation by the “Reich” with the comment, “better Hitler than Habsburg.” Chancellor Schuschnigg and Austrian President Wilhelm Miklas refused to flee and were both arrested by the Germans. Archduke Otto was a declared enemy of the Reich, and orders were given to kill him and his siblings if caught. Significantly, the Nazi invasion of Austria was called “Operation Otto.”

Nine months later, Hitler’s troops entered Prague, Mr. Benes received what he wanted for Austria and fled into exile to London. Czechoslovakia’s sorry fate was a result of the shortsighted policy of its government, but it was sealed by the betrayal by Britain and France in the Munich Agreement, in which the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia was conceded to Germany. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (1937-1940) returned in triumph to London, proclaiming “peace for our time.” Winston Churchill commented correctly: “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor, and you will have war.” After the Munich Agreement, Bohemia and Moravia, the core of today’s Czech Republic, became the Nazi “Protectorat Boehmen und Maehren,” Slovakia received a puppet government by the Nazis and Hungary and Poland annexed some other parts of Czechoslovakia.

Poland, divided between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the late 18th century, reemerged as an independent nation in 1918. The country proved its strength of determination by bravely resisting an invasion by the Soviet Red Army and routing it in the summer of 1920. Nearly two decades later, in September 1939, Germany and then the Soviet Union attacked Poland and divided it. Britain and France, both Poland’s nominal allies, declared war on Germany (and not on the Soviet Union, the other perpetrator), but did not act.

The two countries sent some soldiers near Germany’s western border, yet no shot was fired. Poland fought bravely, but was too weak and thus became another casualty of France and Britain’s betrayal. Hitler and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin (1922-1952) divided its territory, subjecting the population to unspeakable cruelties. A few months later, Hitler’s armies attacked and occupied France, the Benelux countries, Denmark and Norway.

History shows that statehood for smaller entities does not necessarily mean full sovereignty.

The nightmare which Emperor Charles had foreseen and wanted to avoid had come true for Central Europe and much of the rest of Europe.

Another occupation

Central Europe, especially Poland, was exposed to terrible abuses under the Soviet and the Nazi rule during World War II. Its once-flourishing Jewish communities were cruelly annihilated. When the Third Reich collapsed, the whole area fell under the Soviet yoke. What officially was called “liberation” in fact it was a new occupation. The region had little support in the West. The Allies cynically delivered the area to Stalin at the summits of Tehran (1943), as well as Yalta and Potsdam (1945). Millions of Germans who had lived in Central Europe for centuries were forcefully expelled, many of them killed. The Soviet Union annexed the eastern parts of Poland and Czechoslovakia. Poles were expelled from the eastern parts of their prewar state and resettled in new areas in the western region, taken from Germany. The Germans either fled or were deported. Nazi cruelties were followed by Soviet oppression.

As Mr. Churchill said, the “Iron Curtain” had gone down across Europe.

Nationalist sentiments, which triumphed in 1918, did not bring freedom to Central Europe. Celebrating independence should also include the reflection that statehood for smaller entities does not necessarily mean full sovereignty. For smaller nations, it is necessary to seek multilateral arrangements to safeguard their interests. This was the mission of the Habsburg Empire. The Habsburgs saw all language groups as equal and members of the family were all required to speak a number of the languages of the empire.

For centuries, Europe’s east was protected by the kingdoms of Poland and Hungary. To strengthen the area, the kings of Poland, Hungary and Bohemia entered into a cooperation agreement in Visegrad in 1335. This tradition was continued by the Habsburgs, whose realm included Hungary and parts of Poland. Interestingly enough, Poland and Hungary played a paramount role in the collapse of communist dictatorships and the ending of the Soviet occupation in Central Europe.

New dawn

The Solidarity movement in Poland, driven by the working population, shattered the communist system. The election of Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Krakow as Pope John Paul II (1978-2005) was a demoralizing blow to the regime. In the early 1980s, the communist government in Warsaw faced a nasty dilemma: it could either follow Moscow’s order to crush Solidarity with tanks or make political concessions. The communist system in Poland was dying.

Only as parts of a powerful supranational entity these countries could maintain their freedom and independence.

Hungary revolted against Soviet rule in 1956. Russia sent in troops with tanks to crush the opposition, and massive repressions followed. By the 1980s, however, the Hungarian communists also began to realize that the system was no longer sustainable. Archduke Otto of Habsburg, at the time a member of the European Parliament, arranged – with the Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Horn (1989-1990) – a so-called Pan-European Picnic on the border between Austria and Hungary. For the event, the barbed wires of the Iron Curtain were opened in one spot and the minefields cleared.

Soon, thousands of citizens of East Germany could drive their Trabant cars through the opening in Hungary to Austria and further to the Federal Republic of Germany. This trek was globally reported and proved the final blow to the communist regime in East Berlin.

It is remarkable that activities in Poland and Hungary, aided by the last Habsburg crown prince, played such a role in defeating the Soviet challenge to a free and Christian Europe. The main item on Otto von Habsburg’s agenda in the 1990s in the European Parliament was to support a quick accession of the Central European countries in the European Union. Only as parts of a powerful supranational entity, the Archduke reasoned, could these countries maintain their freedom and independence.

Scenarios

Central Europe is a cultural and economic area stretching from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Adriatic and the Black Sea in the southeast. Trade links these countries together. Their economic interests are mostly similar. To deepen these bonds, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland reached a modern-day version of a Visegrad agreement in 1991 on free trade and mutual support in accession to the EU (which took place in 2004). In the last decade and a half, the region received a lot of “cohesion” funds from the EU. These funds were used prudently, and investments in infrastructure resulted in impressive economic growth. Large capital infusions from Western businesses into the region have produced a vast benefit to the whole of Europe. Central European nations can be proud of their accomplishments.

In the last two hundred years, Europe’s economic development centered in the North Atlantic region, which made Central Europe seem somewhat remote. The recent global changes, though, make access to the East more and more vital for Europe. This opens important new opportunities for its central and eastern parts.

There is much to consider as we are commemorating the anniversary of November 1918. Among these matters, the importance of a functioning Visegrad Group and the membership of Central Europe in the European Union must not be overlooked. Ideally, strengthening the Visegrad Four (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) by adding Austria into the group would be desirable, as Western European politicians tend to ignore the economic and geopolitical importance of Central Europe for the continent, and also the region’s needs. An unfortunate tendency to give short shrift to Central European interests is visible again in some capitals in the western part of the EU – for protecting selfish interests or simply through ignorance. Central Europe can only defend its interests by working together. Otherwise, the region may be at risk again due to Western Europe’s shortsighted politics. It is also a necessary basis for maintaining a cohesive policy toward the east.