Africa and foreign influence

In recent years, Europe has mostly abandoned its interests in African countries, leaving a vacuum that is being filled by China, Russia, and Turkey. Current European policy toward Africa is shortsighted, mainly aiming to address the migration crisis. But Europe has an opportunity to form a long-term mutually beneficial partnership there.

In a nutshell

- Sub-Saharan Africa is particularly susceptible to foreign intervention

- Europe’s history there is mixed, but in recent decades has left a vacuum

- Policies that aim for a long-term partnership could benefit both sides

States’ national interests are not limited to their territory or neighborhood. Good economic, foreign and security policy is based on identifying national interests and consequently cultivating spheres of interest, to different degrees and varying levels of priority. Regional and global powers will establish spheres where they can exercise influence. This influence can be used in the short term, mainly to the advantage of the influencing power, or to develop a long-term zone of interest to the countries’ mutual benefit.

Areas where political structures are fragile (regardless of whether they are democratic or autocratic) because they have not been adapted to the local culture or societal needs are especially prone to dependence on or intervention by foreign powers. This intervention can be economic, political or come in the form of soft power.

Sub-Saharan Africa is especially prone to foreign influence, which has overwhelmingly shaped its politics, economics and even culture. There is a long history of this intervention.

Enter Europe

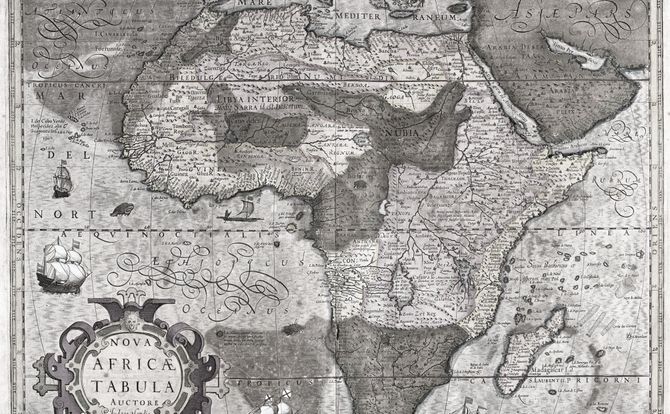

Up to the 16th century, the coastal areas on the Indian Ocean were mostly influenced by Arab and Indian traders. African tribes exchanged gold and ivory, as well as slaves, for textiles, metal products and weapons.

With the arrival of the Portuguese Navy and traders in the 1500s, European countries continued the practice of coastal trading on both the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean coasts. Portuguese traders were quickly followed by the Spanish, Dutch, British and French. Due to the European competition, the various nations established fortified outposts in strategic locations. These not only aided the exchange with the tribal areas in the hinterlands but also served as bases these countries used to secure increasingly important maritime routes to India and East Asia.

The colonial powers put massive efforts into introducing working administrative systems and the rule of law.

In contrast to what was going on in the Americas at the time, European powers were not yet exploring and colonizing the interior, as Europeans were very vulnerable to tropical diseases, especially malaria. Only Dutch and French Huguenots, who were forced to leave Europe, developed a permanent state, based primarily on farming, on the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese increased their holdings and were slowly entering Angola and Mozambique.

The development of quinine and other medical advances in the middle of the 19th century allowed European explorers to make expeditions into the heart of Africa. The continent was no longer an unknown territory. In an unprecedented land grab, the various competing European powers divided Africa into colonies. Boundaries were drawn not according to established traditional lines but the theoretical strategic (and even conflicting) interests of European powers.

Although atrocities occurred in the course of colonization, it must be noted, to the credit of the colonial powers, that they put massive efforts into introducing working administrative systems and the rule of law. They established infrastructure, including roads, railways and manufacturing, and took responsibility for education, both primary and secondary. They improved health systems, leading to a large increase in native populations. Due to colonialism, Africa had a stable political structure from the late 19th century to the 1950s, though it had become a sphere of the relevant European powers.

Downward spiral

In a wave of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s (and, in the case of the Portuguese territories, in the 1970s) the colonies became independent states, supposedly adopting European democratic norms for governance. These new entities were artificial multiethnic states, with borders that had been defined by the colonial powers. None of them evolved from historical or cultural processes. Most of the new countries became failed states: corrupt, haunted by political instability, disease and civil wars. This was the ideal environment for all sorts of foreign intervention.

In several former French colonies (including a former Spanish and a former Portuguese colony) France successfully introduced a currency linked to the French franc, and later to the euro. This was beneficial for France as well as for the 14 African countries concerned (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, the Republic of the Congo, Senegal and Togo), as it provides them with some monetary stability, something other former colonies in sub-Saharan Africa lacked. This is one of the rare success stories of foreign influence.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union began initiatives to destabilize regions in Africa or increase its influence there. Especially notable were its activities in civil wars in Angola and Mozambique. In Angola, mainly Cuban mercenaries fought on behalf of Soviet interests. Zambian dictator Kenneth Kaunda, Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo in the Rhodesian civil war, as well as Samora Machel in Mozambique and Patrice Lumumba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), were just some of the leaders who enjoyed Soviet support.

In the 1960s, the region of Katanga in the DRC and the region of Biafra in Nigeria had very justifiable reasons for wanting independence from their respective countries. These independence movements were put down with terrible bloodshed – the United Nations and major foreign powers supported the sides that committed the atrocities – the national governments.

China’s role

Sub-Saharan Africa has now returned as an area where foreign powers are competing for influence. It remains a very fragile environment.

Africa is also a richly endowed continent with a crucial geographic location between the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans. It has a wealth of minerals, energy, water and agricultural potential, and its population is proliferating rapidly. Many consider the high fertility rate on this continent a curse, but it is rather an opportunity. We must not forget that high birthrates combined with increased life expectancy usually are strong drivers of economic and social development.

China wants to enlarge its sphere of influence to Africa to secure its economic and geographic advantages.

Over the last 30 years, Africa has become a focus of an assertive China, which sees the continent’s potential. China wants to enlarge its sphere of influence to Africa to secure its economic and geographic advantages. Africa had become a strategic vacuum, widely abandoned by its former colonial powers, with corrupt leaders and internal conflicts fueled by the flawed state structures. These factors made it easy to infiltrate and gain influence in the various countries.

China helps African countries fund and construct infrastructure projects, and is becoming an increasingly important market for several of them. More and more Chinese are active in the sub-Saharan region. All of this plays to China’s advantage, allowing it to exercise influence.

European failure

Europe, on the other hand, has lost much of its influence in Africa and for a long time even neglected it as a sphere of interest. European countries mostly limited their activity there to some feel-good humanitarian initiatives – though also some good intentions should not be dismissed, and especially the hospitals and schools established by Christian organizations have been very helpful. In many cases, development aid was wasted and really harmful. It offered the wrong incentives but relieved Europeans’ consciences.

Africa has now reappeared on Europe’s political and public radar, not for the right reasons, but instead because of the threat of mass immigration. Young Africans crossing the Mediterranean are causing a migration crisis in Europe, dividing public opinion, complicating the political landscape and shaking the very foundations of the European Union. This is a terrible sign of European weakness.

European leaders are now traveling through Africa, promising economic and social aid with the hope that it will keep people from migrating as well as help African governments contain the flow and take migrants back. These measures will not succeed, based as they are on false assumptions and lacking any potential for making Africa a zone not only of long-term interest, but also influence. It is an attempt at a short-term fix, and it is bound to fail.

Success can only be based on a strong will to make sub-Saharan Africa an essential zone of interest for Europe.

Success can only be based on a strong will from politicians and the business community to make sub-Saharan Africa an essential zone of interest for Europe, where the influence benefits both sides. This would not be a neocolonial relationship, but a robust partnership. Such involvement in Africa is more than a tremendous opportunity for Europe. It is a strategic necessity. The robust economic involvement of European business is only possible based on strong political support, leading the host countries to respect property rights and the rule of law.

Turkey’s partnership potential

As opposed to many members of the European Union, Turkey has recognized the opportunities in Africa and has begun building on a zone of interest there. Turkish business is very active in Africa and the government in Ankara is getting involved in infrastructure projects – currently on the strategically important Horn of Africa. Turkish Airlines flies to more than 50 destinations in Africa, a clear sign of the country’s commitment. Ankara’s successes have the potential to serve its long-term interests.

Turkey would be an ideal match for European countries in creating a successful partnership with Africa. Further alienating Turkey politically could strengthen Ankara’s alignment with Moscow, although it would not be Turkey’s first choice. Europe and Turkey would be complementary in a partnership with Africa.

The other alternative – bad for everyone involved, especially Africa – would be if Europe, China and Turkey (in alignment with Moscow), were to follow conflicting interests in a political vacuum. Along with African countries, Europe would also be a loser in the long term.