Redressing policies in the Middle East

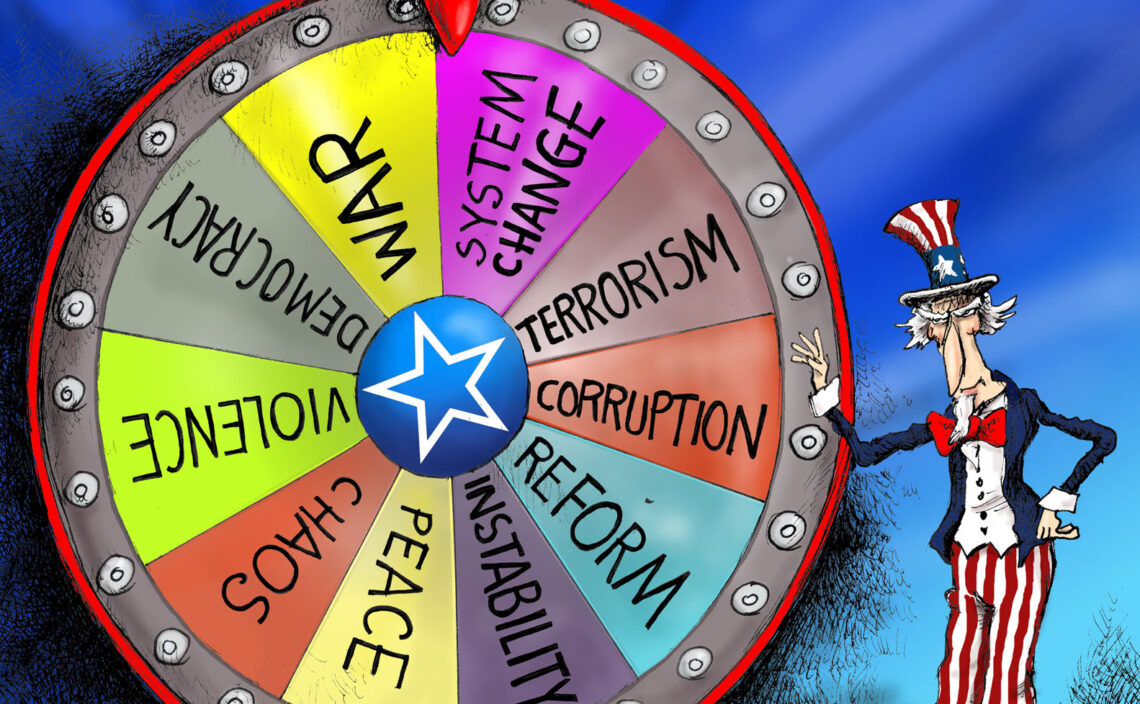

The Biden White House may be repeating old mistakes in the Middle East by turning its back on Saudi Arabia, an ally, and offering leverage to Tehran, a foe. But undermining the powers that be in Riyadh could have disastrous consequences.

Upon taking office, President Joe Biden announced some big changes in the United States’ Middle East policies. The region is one where cultures and continents meet. Some of the oldest civilizations developed between North Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean and Iran, between the Nile in Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. It was populated by various ethnic groups who practiced an array of different religions. It was also where the world’s three main monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, were founded.

For millennia, wars have raged across the region. Due to its strategically important geographic position, foreign powers have regularly intervened in or occupied the area. Persia, Egypt, the Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire dominated the Middle East before the appearance of Islam.

The unfortunate treaties signed to conclude World War I lie at the root of many of the region’s current problems.

Then, Islam spread from the Arab lands. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire became the main Islamic power and ruled most of the Middle East until World War I. The unfortunate treaties signed to conclude that conflict divided the area into British and French spheres of influence and created the states that currently make up the region. This history lies at the root of many of the region’s current problems, as is brilliantly explained in David Fromkin’s 1989 book, A Peace to End All Peace.

This ill-conceived divvying up of land led to another period of foreign intervention that continues to this day.

Postwar interventions

Two new factors emerged after World War II: the rise of Arab nationalism and the Cold War. Arab nationalism was characterized by anti-Western and anti-Israeli sentiment, and was spearheaded by Egypt and Syria, led by President Gamal Abdel Nasser and President Hafez al-Assad, respectively.

The Soviet Union tried to use Arab nationalism to pull countries into its orbit. The West, led by the U.S., wanted to contain Soviet influence around the globe. Washington therefore took a great interest in the Middle East, becoming a stalwart supporter of Israel and pro-Western governments in Arab countries.

At the time, Iran was also a reliable ally of the West. Then, in 1979, the Shah was overthrown (with the West’s support) and in 1980 Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rose to power. He installed the brutal system we now know as the Islamic Republic. Since then, Iran has been the West’s greatest adversary. It calls for the annihilation of Israel, fuels civil wars throughout the region, sponsors terrorism around the world (including Europe) and pitilessly subjugates its own population. It pursued a nuclear program so aggressive that the United Nations implemented hefty sanctions on it.

Under President Barack Obama, the U.S. tried to disengage from the region without leaving Russia and China to dominate its politics. His strategy was to find an arrangement with Iran and restrain its development of nuclear technologies. The Obama administration, perhaps somewhat naively, saw the Islamic Republic as a strong regional power that could help provide stability.

Along with the other permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany, but without the participation of other regional players, Washington and Tehran came to an agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JPCOA). The deal ended the UN sanctions on Iran.

However, it did not require Iran to stop subverting regional stability or sponsoring terrorism, nor to halt its missile program, which threatened other nearby countries – especially Israel and Saudi Arabia. The deal would not have permanently ended Iran’s nuclear program, only delayed its progress.

Diverging paths

In view of these weaknesses, President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the JCPOA and reinstituted sanctions. The White House then focused on normalizing relations between Israel and Arab states in the region, which would also help fend off Iranian aspirations. The resulting Abraham Accords established full diplomatic relations between Israel and two members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. The agreements also seemed to increase the potential for normalization between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Later, Sudan and Morocco also signed normalization deals with Israel. The agreements represent a big step toward peace in the region. They will also enhance trade, innovation and investment, bolstering stability.

The Biden administration came into office having clearly signaled a change in this approach. The focus would be to restore the JCPOA and lift the sanctions on Iran. On the other hand, it would take tough action against Saudi Arabia, a staunch regional ally, in view of its involvement in the Yemen civil war and its human rights violations. Those transgressions include the high-profile assassination of journalist and U.S. resident Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

In foreign policy, it is always advisable to move cautiously rather than rush forward.

In foreign policy, it is always advisable to move cautiously rather than rush forward. The very announcement that the Biden administration wanted to reenter negotiations with Tehran over the nuclear deal aroused worry in the region and weakened U.S. influence, though for short-term commercial considerations the move is popular in Europe. Iran, for its part, did not respond enthusiastically, but immediately sensed it had gained leverage to set tough conditions. It has called for sanctions to be lifted before any negotiations can start.

Aside from the questionable wisdom of such an abrupt change, it also seems blatantly hypocritical to criticize Riyadh for its human rights abuses while opening up to the brutal regime in Iran.

Saudi Arabia is a major player in the region and one of the dominant global powers in the oil and gas sector. Its legal system is based on Islamic law, Sharia, parts of which are incompatible with Western values. However, in recent years Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (frequently referred to as MbS) has spearheaded important reforms, including expanding women’s rights, protecting foreign employees and fighting corruption within the country’s oligarchy. Such transformative changes cannot be implemented hastily, since they could bring about unintended consequences. They also usually require strong leadership.

MbS has not shied away from butting heads with other members of the Saudi royal family, sometimes punishing them with fines or other penalties. That has made him some powerful enemies. He had a good relationship with President Trump and favors normalizing ties with Israel. On the other hand, he is probably by nature – and certainly by necessity – heavy-handed.

At the end of February, President Biden spoke with MbS’s father, King Salman, on the telephone, ostensibly to reaffirm the strong U.S.-Saudi relationship. A day later, his administration released a declassified intelligence report that alleges MbS approved the Khashoggi killing, and announced sanctions and visa bans targeting Saudi Arabian citizens involved in the affair. Though the Crown Prince was not on the receiving end of the sanctions, the move undermined his authority.

Problematic approach

Washington’s new approach has several problems. Certainly, Saudi Arabia must improve its human rights record, but the White House is working to weaken those leading the drive for reform. The released intelligence report bases its conclusions about MbS’s involvement on assumptions regarding his power and relationships, but provides no evidence. All this damages U.S. relations with a crucial ally, Riyadh, to the benefit of a declared enemy, Tehran. In so doing, it opens the door for Russia and China to gain greater influence in the region.

Washington should also be careful not to rush changes, lest it reap a worse result. Examples include the fall of Iran’s Shah (the Carter administration put tremendous pressure on him to leave the country) which as we know resulted in Ayatollah Khomeini’s reign of terror. Another was the ouster of Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak, which was supported by Washington and led to the Muslim Brotherhood (which several countries now designate as a terrorist organization) taking over.

It would be good to avoid a repeat in Saudi Arabia. As Albert Einstein said, the only mistake in life is a lesson not learned. Weakening MbS will delay reforms, while undermining the monarchy could throw the country – and with it the Middle East – into chaos.

The Biden team’s hasty effort to change the U.S.’s Middle East policy could feed the suspicion that it is more important in Washington to reverse the initiatives of former President Trump than to serve America’s long-term interests.