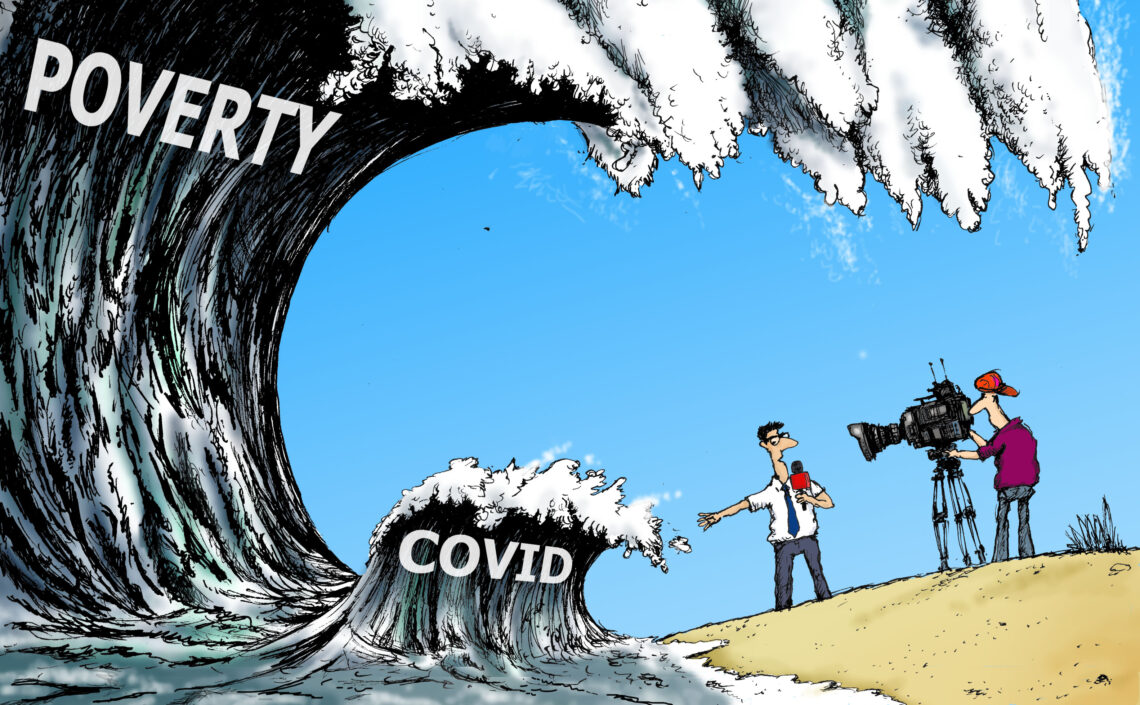

Fighting poverty after Covid: Through ideology or valid economic strategies?

The Covid-19 pandemic has delayed the eradication of poverty in the developing world. The crisis has also strained the weakened and mismanaged economies in the West. To solve these issues, many are proposing unwise economic policies supported by manipulated data.

Before Covid, numbers on the reduction of extreme poverty worldwide were encouraging. The World Bank reported that the share of the global population living below the poverty line had declined from 42 percent in 1981 to less than 10 percent in 2017. Although there might be inaccuracies in the computation of figures, this is an outstanding achievement, especially if one considers that the global population has grown from approximately 4.5 billion to more than 7.5 billion during that period.

The main drivers of this development were globalized markets, trade, travel and entrepreneurship, growth-oriented policies and new technologies. This increasing prosperity enabled more countries to implement sustainable measures on emissions and waste reduction.

Collateral damage

The extreme poverty rate was expected to drop below 8 percent by the end of 2021. Unfortunately, the World Bank now expects that some 100 million people will fall below the poverty threshold due to the economic freeze caused by Covid and the lockdowns in the first half of 2020. The crisis affects mainly South Asia, Africa and some areas in Latin America. It has repercussions for both rural and urban populations, especially the industries employing unskilled workers: construction, mass manufacturing, travel and hospitality, and other services.

Unfortunately, Covid and the lockdowns’ negative consequences will be long-lasting, especially on poverty rates. A second lockdown would be disastrous. It can be debated whether the extent and length of the spring lockdown were appropriate. The measures most probably reduced the number of deaths by Covid-19. But the collateral damage is enormous. The more prosperous parts of the world have suffered, for example, from adverse effects of reduced medical services for non-Covid patients. A study by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom estimates the number of fatalities caused by a lack or delay of treatment at 250,000. One also needs to factor in the psychological stress resulting from the loneliness and destruction of one’s income sources.

The lockdown hit economies that had structural weaknesses.

The lockdown hit economies that had structural weaknesses. The weak spots had mainly been created by ill-conceived policies and administrative measures. The states’ share in the economy has grown disproportionately across the globe. The United States, Europe, China, Japan (and most other countries) indulged in excessive public spending, which has led to unmanageable sovereign debts and heavy tax loads. Furthermore, a jungle of regulations is overtaking the structures of society and the economy. The results are inefficiency, high costs and, finally, arbitrary decisions and corruption.

While the new, highly contagious disease does present difficulties, the panic created by politicians and some virologists, and further hyped by the media, led to exaggerated policy measures early on. Today, however, we have the benefit of hindsight.

The pandemic presents the perfect excuse for incurring new debts.

The real challenge – as discussed earlier – is how to manage the pandemic in poorer countries. A rise in poverty will lead to worse nutrition and medical services, which will cause more disease and casualties. The fight against Africa’s devastating plagues, malaria and tuberculosis, quite successful until now, has been hindered by the recent focus on Covid-19. Many fear that, before long, the two diseases will be on the rise again.

Growing poverty is not only a social problem. It will also hurt efforts to cut waste and emissions in the affected areas. If citizens’ elementary needs are not met, they cannot care for the environment.

Economic witch doctors

What can be done? Different approaches are being considered: some desperate, some ideological, and a few pragmatic and realistic. Governments often throw money at chronic problems – a solution comparable to taking painkillers in the hope of curing a cancer. The root cause, overspending, was neglected in most countries. The pandemic presents the perfect excuse for incurring new debts, so money printing on central banks’ orders remains a common practice. This desperate approach will likely lead to high inflation. The cheap money policy has already created speculative bubbles and inflated asset prices such as real estate. It has distorted business participation and equity markets. The low to negative interest rates are punishing savers. Simply put, this economic policy is not sustainable.

In response to this point, the policy’s proponents have developed a new article of faith in the form of Modern Monetary Theory or MMT. It claims that governments can incur debts and finance them by creating money through central banks: spinning gold from straw like in a fairytale. Many MMT promoters also believe that inequality is a great evil that can only be remedied through forced transfers from rich to poor. This view does not take human nature into account. In the real world, equality exists only before God and the law.

Criticism of the overspending and MMT does not extend to government measures designed to provide liquidity and support to companies, mostly small and medium-sized enterprises, during the lockdown. Such help, however, must only be short-term.

Unreliable figures are circulated to argue that a handful of individuals own the majority of the world’s assets.

Experience shows that prosperity is created through work and entrepreneurship – including a readiness to incur risk and invest effort. Innovation and new technologies are the result of this attitude. In a functioning market economy, opportunities are wide open to most of the population – generally to all willing.

These are the mechanics that have helped roll back poverty before Covid hit. However, the prevailing perception is that markets have failed and redistribution is needed to correct economic problems. Unreliable figures are circulated to argue that a handful of individuals own the majority of the world’s assets. The Oxfam charity group is known for making this claim, although its calculations have been repeatedly proven to be dubious.

Beware of propagandists

Oxfam claims that, in 2018, the globe’s 26 richest people had the same net worth as the 3.8 billion poorest. The organization publishes its figures to coincide with the yearly World Economic Forum in Davos for added impact. It takes its data on the rich from Forbes magazine, making estimates based on sources such as stock exchange valuations. However, these figures do not necessarily include debt against the assets and do not reflect the listed businesses’ real value. Driven up by abundant cheap money, stocks tend to be overpriced. Oxfam figures also misleadingly omit the assets of states and other public institutions that benefit everybody. The Financial Times convincingly demonstrated that Oxfam’s computations are significantly inaccurate, since they do not account for debts and currency exchange rates.

Oxfam, along with many others in politics, media, and other institutions, is raising alarm over what it claims has been a rise in inequality. A 2019 Oxfam report posits that the wealth of 2,200 billionaires grew by 12 percent during the previous year, while the poorer half of the global population lost 11 percent. While the first figure mainly reflects the effect of the asset bubble mentioned before, the second one is highly dubious given the failing global poverty rate at the time. However, such propaganda is used to support claims that administrative wealth redistribution is a necessity.

The key to reducing poverty is not planning and redistribution but opportunities.

Accordingly, the economy should also be planned on the national, supranational and global level. Entrepreneurs’ decisions should be second-guessed, and their property rights limited. Socialist measures of the sort could lead to some reduction in inequality, but it would nearly certainly lead to mass poverty, misery and mediocrity, not only in the economic sphere.

In reality, however, the key to reducing poverty is not planning and redistribution but opportunities. Entrepreneurial efforts and well-functioning free markets provide opportunities for all.

Unfortunately, many well-meaning parties fall into the trap of fake statistics and overstated claims and propose measures that would only worsen our problems. It is surprising and unfortunate that also religious institutions and even the Vatican, whose mission pertains to other matters, believe somewhat naively that redistribution and limiting property rights are solutions. However, that experts, governments in major economies, UN agencies and prominent economists are following this line of reasoning is incomprehensible.