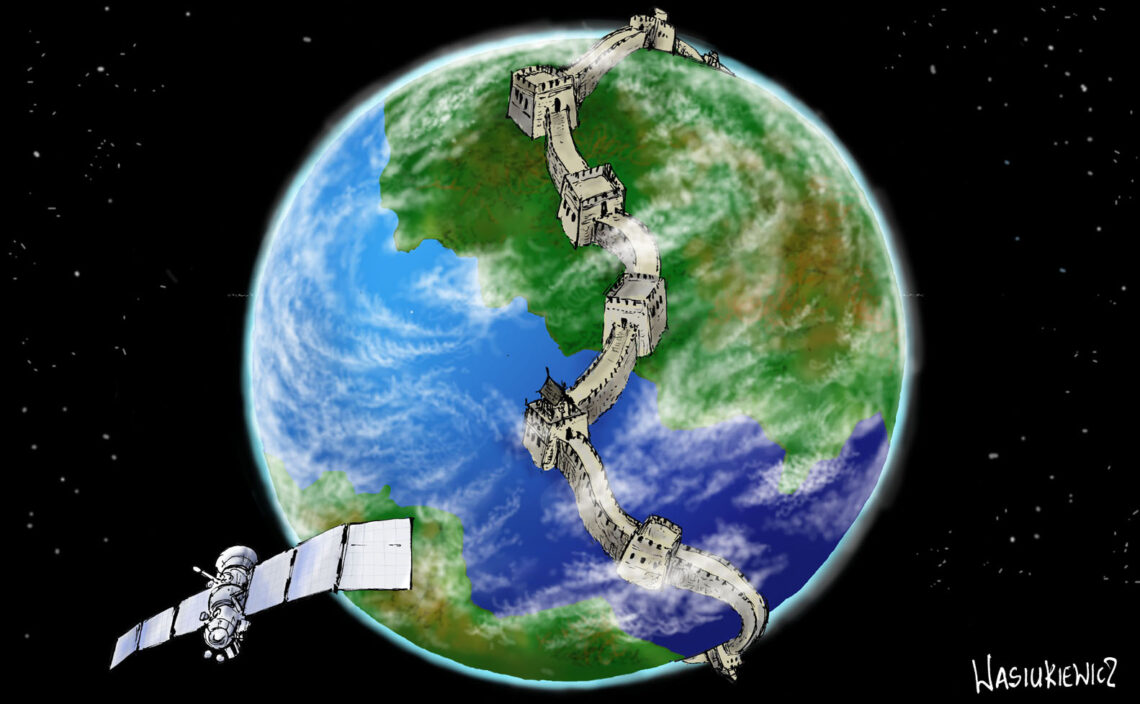

A new bipolar world

A global divide: The recent G7 meeting shows how global politics is fragmenting into two camps. It confirms that geopolitical polarization is occurring. The trend is a fact that we will have to face.

From May 3-5, the foreign ministers of the G7 met in London. The group held its first meeting in 1975 in Rambouillet, France, with the leaders of six countries attending: France, Italy, Japan, the UK, the United States and West Germany. The next year, Canada was added to the group. These were the seven richest industrialized countries, accounting for more than 60 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) at the time. From 1997 until its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia was included in the group, which during that period was dubbed the G8.

Over the past 40 years, the number of summits for the global political jet set has continued to multiply. Many such meetings are meant to boost political leaders’ image at home, giving them an air of international importance. Except for the enormous costs, these get-togethers are of little real consequence and not worth all the media attention they garner. However, this most recent summit was worth watching because it laid bare the new global political fragmentation.

Alliances forming

Ahead of the meeting, British Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab made some provocative statements about Russian disinformation and propaganda destabilizing the West. The UK has identified Russia as the biggest threat to its security, though it views China as its greatest long-term challenge, militarily, economically and technologically.

It will be crucial to avoid heated rhetoric and maintain dialogue.

According to Foreign Secretary Raab, the G7 countries should stand together to defend themselves against propaganda and the challenge from China and Russia. The summit kicked off with a meeting between Mr. Raab and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, underlining the importance of the “special relationship” between Britain and the U.S.

After World War II, NATO was formed mainly to counter Soviet aggression toward Western Europe. Recently, in the Indo-Pacific, the so-called Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) has emerged. It includes Australia, India, Japan and the U.S., which cooperate to counter Chinese assertiveness.

Among the guests that London invited to the G7 summit were Australia and India, meaning the representatives from all four Quad members were there. The move fed rumors that the UK could join the group. Britain has boosted investments in its navy of late, and often sends detachments to the Pacific. At the end of April, in fact, it sent a full-strength carrier strike force to the region.

A hope for dialogue

The meeting in London confirms that geopolitical polarization is occurring. The trend is unfortunate, but is a fact that we will have to face. This is not the first time in history camps have formed on the sides of two big global powers. Such situations can lead to war, but it is not inevitable. It will be crucial to avoid heated rhetoric and maintain dialogue. Avoiding discussion to show moral superiority – a mistake democracies frequently make – is the wrong strategy, as are big summits with mutual recriminations.

We have to accept the increasing global fragmentation without being judgmental.

Small, low-key meetings between decision makers and their closest advisors are generally better. A good example is the Russia-Turkey relationship. The two countries are rivals in the Black Sea region, Eastern Mediterranean, Balkans, Caucasus and Middle East. Presidents Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Vladimir Putin – certainly not friends – meet face-to-face regularly, to keep tensions from rising too high. Most Western leaders would balk at taking a page out of the playbook of these two men, but their strategy is pragmatic, and it works.

Though we can hope that leaders on either side will not use economic and monetary systems as weapons in their conflict, it is, unfortunately, likely. More sanctions could be imposed and currency measures could be used to enforce them. As a result, China and Russia will do their best to challenge the U.S. dollar-based global monetary system. Beijing’s digital yuan project is a step in that direction.

The West considers its rivalry with China and Russia a “systemic conflict.” Russia believes the U.S. and its allies are trying to intervene in its internal affairs and security interests. China sees the West as trying to contain it and keep it from taking a strong global role (and, unofficially, frustrating its hegemonic aspirations).

We have to accept the increasing global fragmentation without being judgmental. Economies and businesses will have to adapt to the new reality. The issue of maintaining supply chains and trade will gain importance. Hopefully, the outcome will be decided less by shortsighted politics than by long-term interests.