Limited room for sovereignty

Ukraine’s ambition to join NATO and the EU triggered a violent reaction from Russia in 2014. Today, as the Kremlin threatens to invade Ukraine to reverse its continuing pro-Western orientation, the country cannot count on the West to join the fight. Kiev, and also Tbilisi, would do well to define their geopolitical options pragmatically.

The rules-based international order is a great concept, but it has several weaknesses. The first question is: who sets the rules? Second, how are the rules enforced? There are many theories, but the system does not work anymore.

In an ideal world, the rules would be defined through inclusive negotiations, and the system would respect all countries’ and regions’ right of self-determination. Also, there would be benevolent powers to enforce the rules.

During the Cold War, we had a balance between the United States and the Soviet Union that stemmed from the threat of mutual nuclear annihilation. After the Soviet Union’s collapse, the U.S. assumed the mantle of global hegemon and guarantor of the rules-based order. Over time, however, the norms based on Western standards encountered dwindling acceptance, and the concept has become obsolete.

Big powers get their way

The part that was never genuinely respected by national and territorial states is the right to regional self-determination. At the same time, national states jealously guard their sovereignty. Habitually, they maintain that regions belong to them. In an orderly and peaceful world, states would recognize that regions belong to their local people and not the nations themselves.

If a country needs to rely on a faraway power to protect it from the designs of its neighbor, its position is precarious.

Unfortunately, geopolitics teaches us that smaller states need to tread lightly when they make sovereignty claims. The task is even more delicate on the periphery of the larger powers.

The danger is further exacerbated during periods of intense great power competition. If a country needs to rely on a faraway power to protect it from the designs of its neighbor, its position is precarious. Countries that fall in this trap often end up being betrayed and abandoned, which happened to Germany’s eastern neighbors in the wake of World War II.

Today, we see parts of Central and Eastern Europe in exactly such an uncomfortable situation. These countries used to be members of the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact or, as in the case of the three Baltic states, Ukraine and Georgia, parts of the Soviet Union. These five countries are of huge strategic importance to Russia. As members of NATO and the European Union, the Baltics are in a more advantageous position than Ukraine and Georgia.

From Moscow’s perspective, it is intolerable that Ukraine and Georgia might become de facto allies of NATO and the EU. Such a prospect triggered Russia’s reaction in 2014, after the EU’s poorly prepared Eastern Partnership proposal. (This description is meant as a realistic assessment of the situation, not a tacit approval of Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine and, before that, against Georgia.)

For both these countries, Russia represents, on the one side, a daunting political threat, on the other – an indispensable trading partner. Being in such a position is highly distressing. However, confronting Russia while betting on Western help is not a sustainable policy response in this situation.

Look at the tension surrounding Ukraine today. Moscow wants to continue influencing the country. Over the past few years, the U.S. and NATO have supported the Ukrainian state with military equipment and training. The Kremlin sees this policy as NATO’s involvement in Ukraine. It has responded to it by building up its armed presence close to the Ukrainian border and launching new cyber and disinformation campaigns to destabilize its government. The U.S., for its part, ramps up its military and political support for Ukraine.

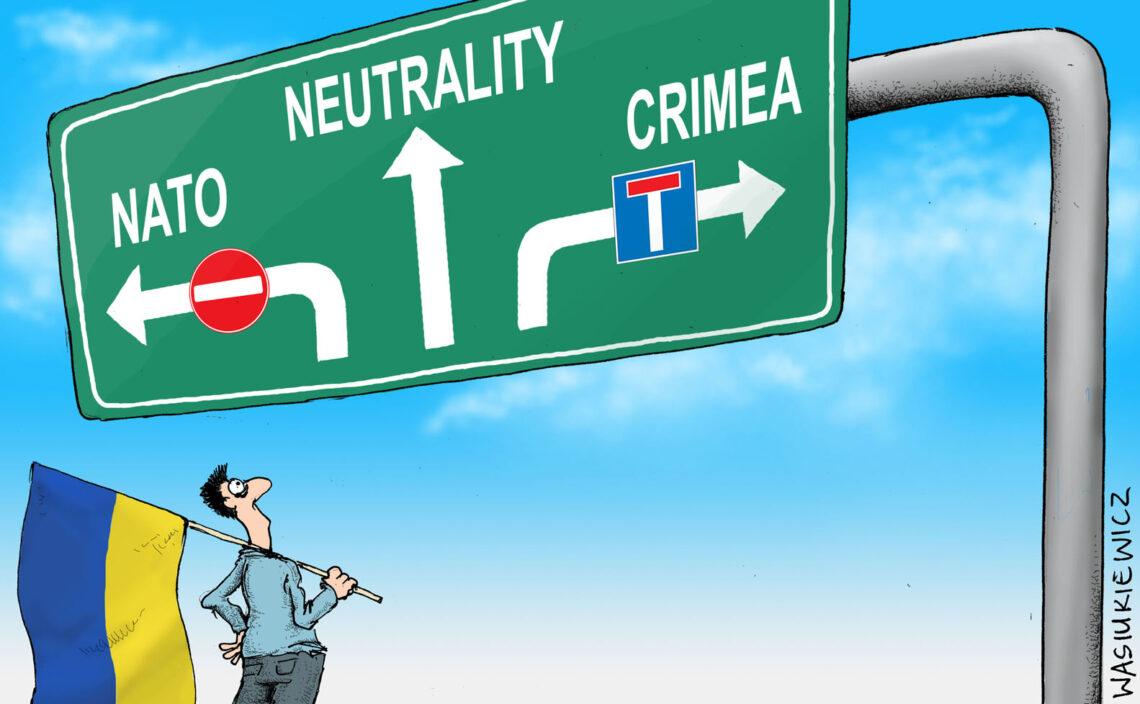

The next best thing: neutrality

The West is ready to offer equipment and training. However, it is not prepared to go to war for Ukraine. U.S. President Joe Biden is threatening Russia with economic sanctions, but little economic interaction is left between Russia and the U.S. European countries are more involved in trade and investment, but Brussels’ threat of sanctions against Russia rings hollow too. Europe depends as much on buying natural gas from Russia as Russia depends on selling it. The Western sanctions imposed on Russia after its annexation of Crimea in 2014 have not changed the Kremlin’s policies.

Russia is not very likely to invade Ukraine now. But its military buildup evidently serves to pressure Ukraine and the West.

Looking to the future, the two countries would do well to concentrate on developing resilient domestic economies.

A solution to the standoff does not lie in Washington, Brussels, London, Paris or Berlin. Ukraine and Georgia themselves need to define their pragmatic options. Unfortunately, realpolitik will have to guide this search. In the end, the two countries need to find a modus vivendi with Russia. The West could help in the negotiation process, but its role should not be overvalued.

This must be a harsh reality for Ukraine and Georgia and their patriotic populations to face. The endless talk of values-based support flowing from Washington and the European capitals is just a game to lull the conscience of Western citizens; the actual policy is toothless.

Looking to the future, the two countries would do well to concentrate on developing resilient domestic economies. This strategy would bring more benefit to Ukraine than battling for a return of Crimea. Both should take advantage of their locations at the crossroads between Europe, Russia, Turkey and the Middle East. The interests of Europe and Turkey can be leveraged.

Striving for neutrality between Russia and the West, just as Austria and Finland did after World War II, appears in these circumstances the best option that Ukraine and Georgia can pursue. Having won neutral status, Austria succeeded in ending foreign – including Soviet – occupation in 1956 and benefited from a highly advantageous position in foreign trade. The country briskly developed when sandwiched between NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Similarly, Ukraine and Georgia could strive for trading without limitations with the EU, Russia and Turkey.

I am stating the above not because I am happy that realpolitik often limits the choices of smaller countries. This analysis rests on what one must consider the hard facts of life.