Lessons from the Swiss referendum on the CO2 law

Swiss people are highly conscious of environmental challenges. If Switzerland narrowly rejected legislation to limit CO2 emissions in a recent referendum, it was because many people refused to bow to debate-quashing tactics in the process of formulating policies.

In a referendum on June 13, 2021, Switzerland’s sovereign – the Swiss people – rejected the so-called CO2 law to curb greenhouse gas emissions. The legislation, which would have hiked fees and taxes on fuels and airline tickets in 2022, will not come into force.

The intent was to help keep the earth’s average temperature rise to less than 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels – and even to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius. According to the proposal of the Federal Council (the Swiss government) and the Federal Assembly (parliament), by 2030 Switzerland was supposed to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to half of 1990 levels.

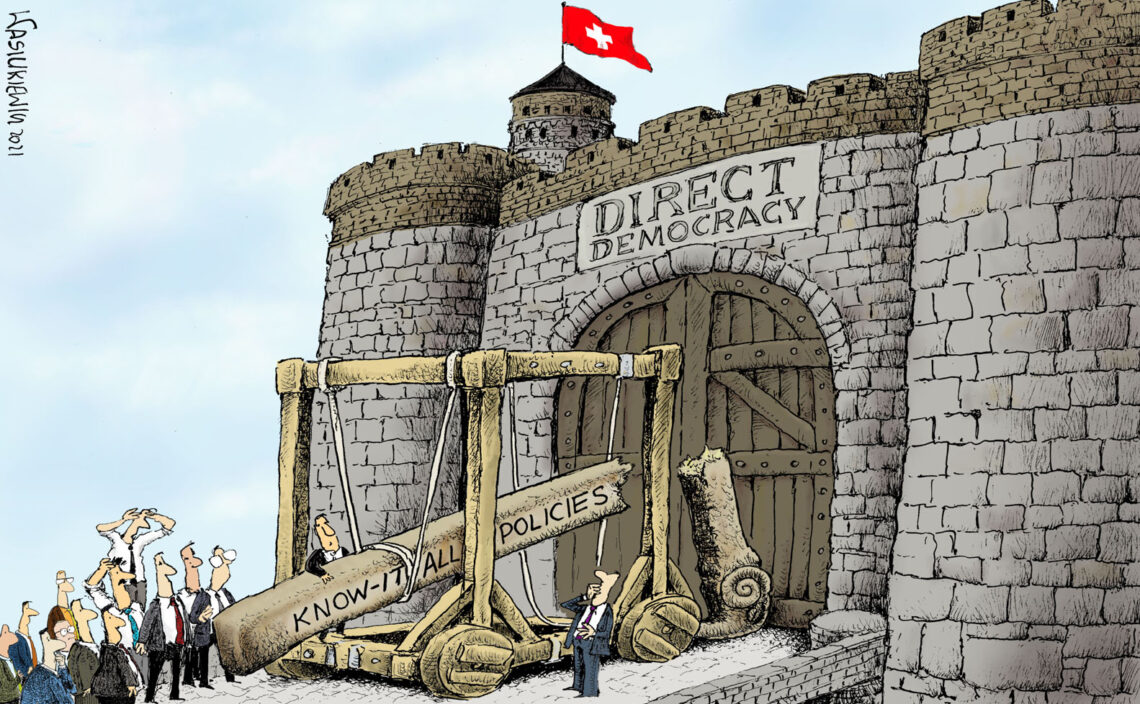

The Swiss system of direct democracy empowers citizens more than a representative democracy. It allows major policy decisions to be subjected to referenda and citizens’ assessment, effectively correcting the excesses of politics driven by party interests.

Citizens are tired

A heated debate preceded the June 13 referendum. That was certainly a good process. The CO2 law was supported by an overwhelming majority of Swiss institutions: the government, most major political parties, trade unions, employers’ organizations, large businesses, and most media. The legislation was presented as the obvious, only available solution. The objective, after all, was to protect the world from disaster by abiding by the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Nevertheless, the Swiss narrowly voted “no.”

Interestingly, the group of voters clearly in favor of the legislation was those aged 65 and more. According to tabulations by leading media organization TX Group, those in the 18-35 age bracket rejected the measure by approximately 58 percent. The outcome was shocking to much of the political, intellectual and media establishments in Switzerland and abroad. Suggestions were made that the Swiss population must not be aware of the problem and is somewhat backward. This is probably not the reason. The Swiss tend to be highly aware of the environmental problems and have been taking pragmatic, very effective measures to protect air, water and natural habitats. Most people in the country support this approach.

The problem likely lies somewhere else: citizens are tired of hearing orders and solutions without alternatives: “You have to accept the Paris Agreement, as it is the only way to save our planet.” One may be very highly appreciative of the necessity to curtail pollution, unnecessary emissions and waste, and still find it difficult to accept that a single international agreement – the one signed in Paris in 2016 – or one legislative proposal hammered out by a government and its allies, represents an exclusive path to salvation.

People – not only the Swiss – might be tired of measures being forced upon them by know-it-all politicians acting in cahoots with selected scientists and using Armageddon-level scare tactics to silence dissenters. Under the pretense of the climate threat, these actors quash discussion and ignore that a healthy debate is the basis of any functioning society.

The culture of public debate still thrives in the Alpine confederation.

During the recent outbreaks of the Covid pandemic, governments and a small cadre of scientists declared the lockdown the only feasible response to the health crisis. Those who questioned the approach were immediately marginalized and labeled as “covidiots” or worse. This is not to deny that lockdowns might be necessary for some situations; however, a robust debate around the science, economics and politics would have inspired more public trust by forcing national and local leaders to explain the policy better.

In the context of the Swiss governance system, accountability is crucial. Clear and understandable argumentation is key to formulating a successful policy. Attempts to rig the debate or, worse, substitute facts with threats, do not work. The Swiss sovereign has rejected several proposed agreements with the European Union. Whether this was for good or ill, the future will show. But it proves that the culture of public debate still thrives in the Alpine confederation. Direct democracy, as in Switzerland, offers a big advantage: people can genuinely speak up and formulate their wishes. This freedom leads to government accountability. Threats and manipulation never work long-term.

The Swiss population and economy will do more – relative to its size – than most other countries to protect the planet’s future. The Swiss are not backward, not free riders nor cherry pickers in the international economic community. On the contrary, they are a society of hardworking realists who vigilantly protect their freedom of speech, opinion and debate.

Heed this warning

The Swiss rejection of the CO2 law, especially by the younger members of society, should be seen as the final warning to other countries. Attempting to substitute a free debate with solutions imposed from above amid threats to the opposition is a recipe for failure.

In Germany, the renowned Allensbach public opinion research institute found that most Germans believe that, in certain areas, speaking one’s mind could be damaging to one’s social standing and career prospects. This attitude, not the blind adherence to the Paris Agreement (with all the merits it might have) – is the worst danger that our society faces these days.

Tackling the challenges of pollution, heat-trapping emissions and civilization’s waste will be more successful if solutions stem from non-constricted, merit-based debates that include dissenting opinions. The Swiss have rejected the other way, with its endless threats, arm-twisting and denunciations.