Respecting Turkey’s position

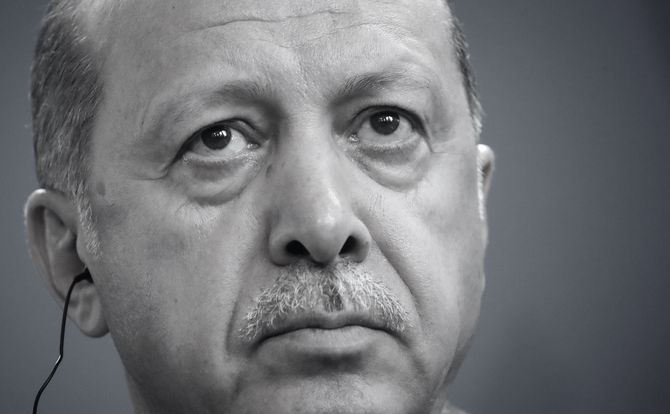

The opposition victory in Istanbul’s mayoral election was seen widely as a defeat for Turkish President Erdogan, who is criticized in the West. Yet Mr. Erdogan’s detractors underestimate the challenges of adapting to changing circumstances of Turkey, where the Kemalist principles of secularism and isolationism no longer suffice.

In a nutshell

- Geopolitical conditions have forced Turkey to move away from its Kemalist political model

- President Erdogan’s conservative, free-market Islamism is a rational response to new challenges

- Foreign critics fail to understand the historic context of his democratic mandate

On June 23, 2019, Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city with 15 million inhabitants, had its second mayoral election in three months. The first, in March, ended in a dead heat between opposition candidate Ekrem Imamoglu, the victor by only 0.2 percentage points, and Binali Yildirim of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). After that vote was annulled by Turkey’s Supreme Electoral Council, Mr. Imamoglu won the do-over by a convincing margin of 54.2 percent to 45 percent.

The election results made headlines because they were widely viewed as a defeat for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. However, they should be viewed instead for what they are – a sign that democracy still works on the Bosporus.

An overlooked centennial

Perhaps a more important date to remember is May 19, the centennial of the outbreak of the War of Independence that led to the establishment of the modern Republic in 1923. This anniversary is widely ignored abroad, even though it is vital to understanding Turkish policy.

A century ago, the Ottoman Empire lost World War I, along with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The victorious allies considered Turkey as an entity to be filleted and carved up, as shown by the Treaty of Sevres (1920), which dismembered the Ottoman lands in an irresponsible fashion. Turkey lost all its possessions in the Middle East, the Aegean islands, control of the Bosporus and Dardanelles Strait, along with other territories. Anatolia and the empire’s European portions were occupied by Britain, France, Greece and Italy.

One hundred years ago, Ataturk embarked on a Reconquista of Turkey.

On May 19, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, (later called Ataturk, meaning father of the Turks) was rowed ashore at the Black Sea port of Samsun with a small group of staff officers. From there, he embarked on a Reconquista of Turkey. An experienced field commander with a brilliant combat record in World War I, he managed over the next four years to defeat the powerful occupying powers and their local proxies, reconquering the whole of Anatolia and territories in Europe that comprise today’s Republic of Turkey. After some adjustments and painful population resettlements, mainly from and to Greece, the foreign powers had to recognize Turkey’s sovereignty in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923).

At that time, this deal was probably the best solution, though it was still painful and inequitable for Turkey. However, Ataturk, a political realist, acquiesced and modern Turkey was created. He ruled as the new republic’s president until his death in 1938.

Kemalism and its origins

Under Ataturk’s guidance, the country concentrated on internal modernization. According to the president’s view, Turkey had lost a war and its empire because of its governmental system and the influence of Islam. Both, in his estimation, did not measure up to Western national systems. Accordingly, Ataturk limited the role of Islam in everyday life, prohibiting traditional headscarves in schools and government offices, while replacing Arabic script with a Latin alphabet adapted to Turkish phonetic requirements. Turkey’s legal system was also adapted along European lines.

These reforms were designed to create robust institutions. The backbone of the system was the national army, which focused on guarding Turkey’s territorial integrity and constitutional order, based on the secular national state. Due to Turkey’s sensitive strategic position, the role of the military was crucial – first in protecting the country’s neutrality during World War II, and then while containing Soviet expansion during the Cold War.

The secular Turkish state that emerged between the two world wars remained very much based on its founder’s vision, which is why the system was called Kemalism. Turkey became an essential part of NATO and today has the second-largest defense force in the alliance, after the United States.

Adapting the system

Once formal negotiations for EU accession began in 2005, Turkey – at Brussels’ request – started to dismantle the army’s role as a political arbiter and guardian of the constitution.

This process was accelerated by a series of show trials against alleged military plotters and ultranationalists associated with the so-called “deep state,” most notably the Ergenekon (2008) and Balyoz (2010) cases. Both conspiracies were allegedly aimed against the government. Even though many of the defendants in these cases ultimately had their convictions overturned, their effect further neutralized the military as a political force.

Isolationism and nonintervention no longer worked so well in the 2000s.

Broader changes were underway as well. Ataturk’s focus on internal development – embodied in his slogan, “Peace at home, peace in the world” – was a good approach for the 20th century. But the isolationism and noninterventionism that defined the Turkish republic’s foreign policy no longer worked so well in the 2000s. Turkey’s neighbors in the Middle East had become increasingly unstable, while the political influence of contemporary Islam had grown vastly more powerful.

Turkey remained the largest and most stable country in the region, but geopolitics had returned. As a regional power, Ankara could no longer stay inactive.

Different neighborhood

In the 19th century, most of the Islamic world was colonized by European powers, with the exception of the Ottoman Empire and Iran. After World War I, the formerly Ottoman-controlled areas of the Middle East were included in the British and French spheres of influence. This changed in the second half of the 20th century, however, as the whole region became sovereign with the collapse of European colonialism.

Some countries amassed wealth through fossil energy. Others, however, started out as artificial constructs and became increasingly destabilized, as in Iraq after the fall of the monarchy and Syria in the wake of the Arab Spring. Neighboring Iran came under the sway of radical Shia theocrats and became a fundamentalist Islamic regime. These developments in Turkey’s immediate neighborhood had consequences that Ankara could no longer afford to ignore.

Regional changes were also taking place in the Caucasus, the Black Sea area and the Balkans. Russia became an important trading partner. Moscow’s resurgent power and influence, especially regarding energy and gas pipelines, had repercussions for Turkey and the EU.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s bid for EU membership became a constant uphill battle for the country. Ankara’s negotiating partners in different European capitals used evasive tactics, setting strict conditions but displaying little desire to include Turkey. This left a bitter aftertaste on the Bosporus.

The increasing self-confidence of Islam also had important consequences for Turkey. Systematic discrimination by the secular state against Islamic practices, such as the symbolic ban on the headscarf, was no longer tenable.

Mr. Erdogan’s AKP promised to bring solutions and it delivered.

The conservative, free-market, moderate Islamism of Mr. Erdogan’s AKP arose in response to these challenges. The party promised to bring solutions and it delivered. The government’s economic policies gave scope for businesses to grow, with positive effects on the economy and society. Huge infrastructure projects were carried out.

The consequence was that Turkey moved away from Kemalism. As President Erdogan and the AKP solidified their democratic mandate, the army lost its leading political role, and constitutionally enshrined secularism lost its chief protector.

Active measures

The new conditions in the Middle East require a stronger political and military presence from Ankara. Turkey has to protect its interests, which cannot always be fully aligned with American or European ones. Turkey’s immediate sphere of interest includes the eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Middle East and parts of North and East Africa. Its geographical position also requires it to cooperate with and at times confront a variety of regional and global powers, including Russia, the U.S., the EU, Iran and Israel.

Another domestic and international concern is the Kurdish issue. Large areas of Turkey contain mixed Turkish and Kurdish population. Kemalism recognized only one nation and one language, in keeping with its European model. The Turks and Kurds are used to living together, but tensions between them grew as a by-product of nationalism, and were later inflamed by insurgency and terrorism. It will be a difficult legacy to overcome.

Turkey’s relationship with the West can sustain a rocky transition period.

The much-criticized military intervention in northern Syria is explained by Ankara’s concern to prevent that region from becoming a base for Kurdish insurgents and terror attacks in Turkey. In Iraq, for example, Turkey maintains cordial relations with the Kurdish Regional Government, as shown by the friendly visit of new KRG President Nechirvan Barzani to Ankara in June 2019. There is still hope that both sides will move in fits and starts to a mutually satisfying internal resolution of the Kurdish question.

Areas of friction

As Turkey leaves Kemalism behind, President Erdogan has also questioned the international order that underpinned it. He has criticized the Treaty of Lausanne as unjust. Objectively, the Turkish leader has a strong case, although the document must be weighed against his country’s position at that time and the improvement it represented over the shameful “dictate” of Sevres in 1919.

While there are areas of friction between the two sides in political and security matters, Turkey remains an important partner for the West. The relationship is so vital that it should be able to sustain a rocky transition period, when things do not necessarily go as planned.

President Erdogan and the AKP have been criticized in the West as ruling in violation of the principles of liberal democracy, especially after the attempted coup of July 2016. Yet we should recognize that the coup itself was neither democratic nor constitutional, and that it was directed against a democratically elected government.

Mr. Gulen’s reputation as a “thinker” should not obscure his ambitions as a power-seeker.

Assessments of the coup’s background and motivation are still controversial. Members of the Gulenist movement appear to have been the driving force. Muhammed Fethullah Gulen, whose reputation as an Islamic “thinker” should not obscure his ambitions as a power-seeker, was a political ally of Mr. Erdogan and the AKP in the 1990s. Since that time, followers of his movement began to occupy systematically many key positions in Turkey’s educational and judicial systems, as well as in the military. However, an estrangement began between the two men that drove Mr. Gulen into American exile.

By the time of the 2016 coup, the AKP regarded Gulenism as a danger to the state. With advance warning of his attempted overthrow, President Erdogan had time to prepare a strategic reaction. In this sense, the coup provided ideal justification for a nationwide purge.

Economically exposed

Turkey’s present economic problems and the depreciation of the Turkish lira are widely blamed on the policies of the AKP government, President Erdogan and Finance Minister Berat Albayrak, Mr. Erdogan’s son-in-law. Interference, similar to the political nudging in Europe at the European Central Bank and in the U.S. as well, has driven the Turkish central bank to maintain low rates, despite high inflation.

A basic misunderstanding of economics, i.e. that high interest rates cause high inflation, is not helping the situation. The continued policies of growth at any price and heavy foreign borrowing have made Turkey very vulnerable to currency crises, a typical emerging market problem.

Unlike many dictatorships, Turkey has a vigorous constitutional opposition.

However, the main reason is the state of the global economy, which hits emerging markets first and stronger. Similar situations can be seen in Indonesia, Mexico and Brazil. It will be one of the main tasks of the government to reset the economy and give confidence to foreign investment in order to have a good chance of being reelected. Due to the global economic situation, this will be a hard task.

To be sure, Mr. Erdogan has secured a sweeping expansion of executive powers that has been decried in the West as illiberal. His constitutional reform is criticized for not sufficiently respecting the independence of the judiciary and limiting freedom of the press. The president’s closest advisors, however, and a good part of Turkey’s population are convinced that the country’s difficult geopolitical situation demands strong leadership with wide powers.

Respect: earned and given

Legitimate criticism has its place. True objectivity, however, requires an understanding of the historical context and geopolitical challenges facing specific regimes.

In contrast to many dictatorships, Turkey continues to have a vigorous constitutional opposition. Even some prominent members of the AKP, including former President Abdullah Gul (2007-2014), former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu (2014-2016), and former Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan have recently resigned from the AKP and are reportedly forming a separate political movement.

Such developments, along with the results of the Istanbul mayoral election, are proof that democracy and constitutionalism are working in Turkey. An essential feature of democracy is that politicians must get results to be reelected. But it is also true that democratic governance takes different forms in different countries, because it is subject to different conditions.

Quite properly, Turkey’s head of state respected the wishes of Istanbul’s voters and congratulated the new mayor. President Erdogan also won a fair election, which entitles him to similar respect from foreign critics.