The future of Europe’s car industry

The European car industry is losing ground as regulation, protectionism and weak productivity collide with global competition, especially from China.

In a nutshell

- Europe’s car industry is gradually losing competitiveness

- Regulation and protectionism are raising costs without delivering innovation

- A widening productivity and skills gap threatens long-term viability

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

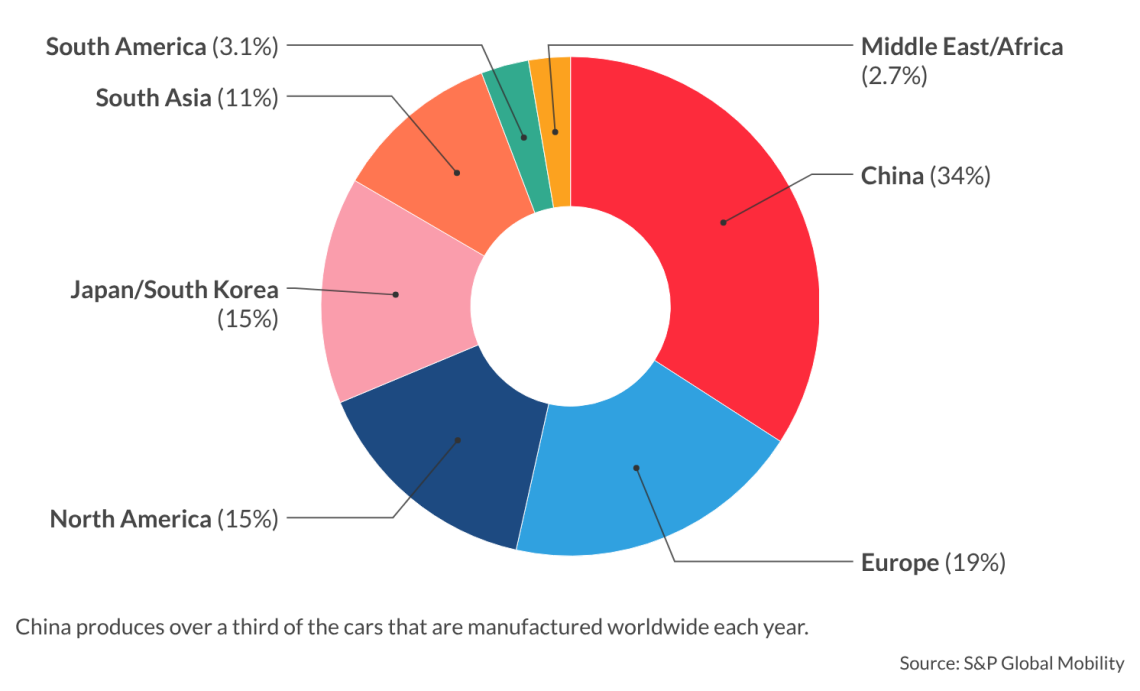

The crisis of the European car industry continues to make headlines. While global car sales have increased from 66 million to 76 million between 2012 and 2023, European car production has declined from nearly 13 million to just 12 million units. In terms of market share, this corresponds to a drop from 19.4 percent to 15.9 percent.

These figures justify serious concerns. The picture becomes even more worrying when one considers the sales of the top 10 global manufacturers of electric vehicles (EV) in the first three months of 2025. Six are Chinese (producing 93.6 percent of the top-10 group), one is American (3.1 percent of the total) and three are German (3.3 percent of the total).

European EV producers are still doing well on the old continent. They accounted for 46.5 percent of European EV sales in September, partly thanks to their willingness to cut profit margins and the high tariffs (up to 35 percent) imposed by the European Union on Chinese EV imports.

This helps explain why stock markets have mixed feelings about the future of the European car industry. Although Stellantis and Renault shares have dropped 20 percent since January, shares of German car producers have risen.

Pressures shaping the European car industry

Three factors are likely to shape the future of the continent’s car production. The first is regulation, particularly within the EU. The second is whether today’s protectionist barriers can be sustained and whether they actually work. The third is Europe’s widening productivity gap.

The car industry has fallen victim to the green transition frenzy. From 2035, all new cars and vans sold in the EU will need to comply with a 90 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions. When the original zero-emissions framework was approved in March 2023, European carmakers largely refrained from opposing it, despite the domestic market’s central importance to their business models.

At that time, the European car industry was already sputtering, but the insistence of German manufacturers carried the day (Poland voted against, while Bulgaria, Italy and Romania abstained). With the benefit of hindsight, European car companies made major mistakes. They believed that clean energy would be cheap and therefore encourage consumers to buy more cars; that green regulation would come with generous subsidies to production; and that European technology was not far behind China. Of course, the greatest mistake was believing that subsidies and regulation would be a suitable solution to thin margins, low productivity, wanting entrepreneurship and inadequate innovation.

Facts & figures

Less than three years have gone by, and most experts now agree that the European zero-emission policy has had negligible effects on climate change. More strikingly, the size and consequences of those mistakes are apparent: Non-fossil energy is not cheap, production costs are high, subsidies are lighter than anticipated, infrastructure like battery charging points is far from adequate and the technological gap between Europe and Asia has widened.

Not surprisingly, the car industry and the European Commission are currently trying to find solutions without losing face. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said the commission is likely to ease some constraints, revise the 2035 deadline and offer new subsidies, notably to battery producers. However, the recent cut (from 100 percent to 90 percent reduction in CO2 emissions) is too little and too late, deregulation is still out of the question and vague statements about – and hopes for – new sets of rules create further uncertainty and discourage long-term investments.

The costs of protectionism and overregulation

Protectionism is a double-edged sword. As expected, European consumers are bearing its costs. They could either respond by buying more expensive European cars or by postponing replacing their aging vehicles.

The figures are not encouraging. Older car fleets increase pollution and undermine road safety. To keep the average age of the EU vehicle fleet constant, households should buy some 20 million cars annually. The present figure is less than 13 million. Protectionism appears unable to keep Chinese carmakers out, but it does give EU producers some breathing room to balance their books and avoid disaster, while also providing EU authorities with new resources to fund their programs.

Moreover, protectionism will become increasingly porous. Chinese producers will be assembling their cars in third countries to circumvent the heavier import duties. They are planning to intensify their network of global joint ventures and sidestep tariff walls altogether. No European plan B is in sight. Yet, it is badly needed before its competitors retaliate by restricting key exports like rare earths or disrupting our supply chains.

Entrepreneurship and innovation in the old continent are in short supply. Data on economic growth, productivity and fixed investments offer plenty of evidence. In contrast with some popular economic thinking, pervasive regulation, overly ambitious governmental programs and heavy public debts have been part of the problem, rather than the solution.

This explains why Europe has lost its edge in the scramble to secure access to battery supply chains. Many producers have reacted to outside competition by cutting costs and relocating to low-labor-cost areas. These policies may provide some leeway in the short term, but they have little chance of succeeding in the long run. Car manufacturing is becoming far less labor-intensive – even if battery production still requires significant labor.

More by economic policy expert Enrico Colombatto

- The myths of central bank independence

- Tariffs bring adjustments, not global economic ruin

- How tariffs will shape inflation

Developing and rapidly adopting successful electric power technologies is crucial. Right now, European employers struggle to find highly qualified workers and remain hesitant to commit to long-term strategies. At the same time, EU authorities and national governments seem to be more interested in central planning, detailed regulation and repeatedly taxing big business than in creating a suitable environment for innovation.

European industry has no future as long as policymakers treat wealth as a fixed pie to be redistributed according to “fair” criteria and overlook the fact that regulation and taxation do not drive growth. The car sector is no exception.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.