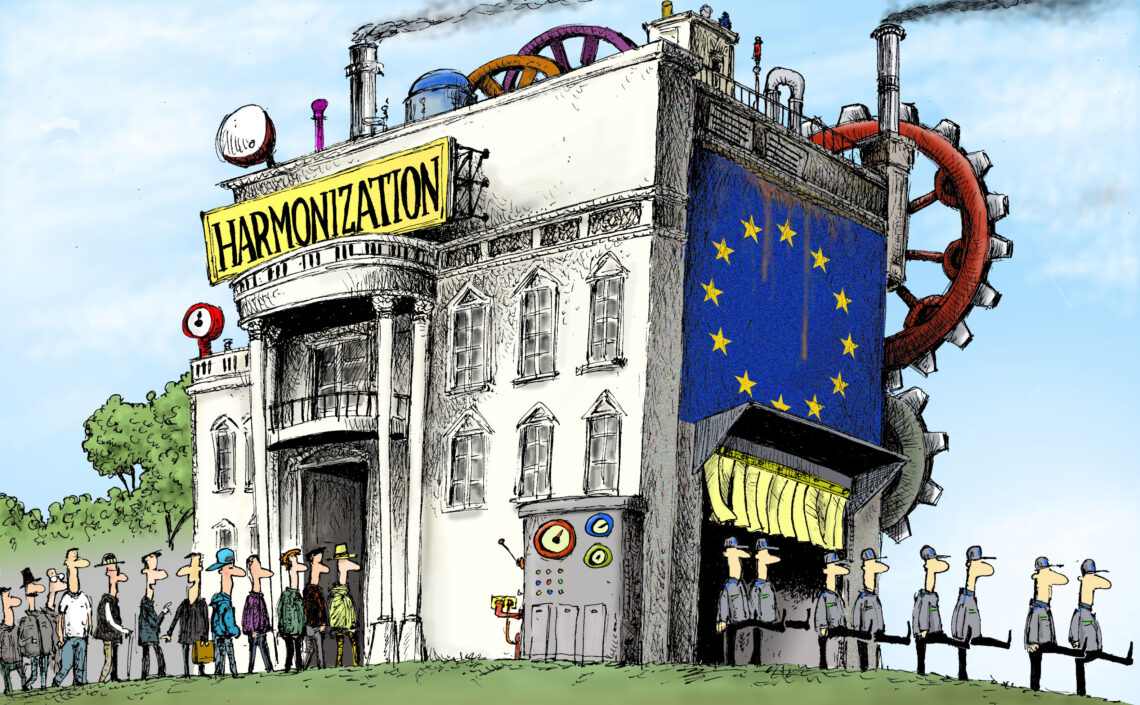

Europe needs integration, not harmonization

Europe was never a house where everyone lives under the same rules, but a village in which all the houses work together. Today, however, harmonization is the dominant dogma used to brand skeptics as “anti-European” – when Europe’s strength used to be its variety.

The European integration process was an exciting and ultimately successful endeavor. At first, it was centered around the enthusiastically accepted French-German friendship, with the Benelux countries and Italy joining in. The enlargement that followed brought new members and was crowned by the accession of the Central European countries that had suffered behind the Iron Curtain under the Soviets’ brutal socialist yoke.

The European Union took its strength from the diversity of its regions. Besides providing a single market, the EU should protect free trade, private initiative and freedom, while respecting decentralization, self-determination and the principle of subsidiarity.

Unfortunately, politicization, bureaucracy and centralist ideas gained momentum both in member countries and at the EU level.

This trend toward harmonization and centralization is the bureaucratic cancer that is eating away at the European Union. It has led to friction and inefficiency, as well as political and economic paralysis. Fault lies not only with Brussels, but also with the member states.

Harmonization, disguised as integration, became dogma. Any criticism was frowned upon as ‘anti-European’.

Harmonization, disguised as integration, became dogma. Any criticism of measures proposed to achieve an “ever closer union” was frowned upon first as “euroskeptic,” and later as “anti-European.” The label became a tool to silence opposition not only from EU members, but also inside countries. This has limited crucial debate and violates a fundamental principle of freedom and democracy: plurality of opinion.

Freedom to criticize

When French citizens criticize the government in Paris, they are not denounced as anti-French. The same is true for any other European country: criticizing the government is considered the right of any citizen. Not so when questioning the trend toward over-harmonization in the EU. Do that, and you are branded an anti-European. The system is a sort of soft authoritarianism that silences people who want to contribute to Europe’s development. Their visions can provide valuable alternatives to single-minded “official policies” or political and administrative processes.

A case in point is the beginnings of the Alternative for Germany (Alternative fur Deutschland, or AfD). Today people call the party populist and right-wing nationalist, but it has nevertheless become an important political force. Initially, it was neither right-wing nor populist. It was founded by three well-known economists, who centered the party’s agenda around the weaknesses in the architecture of the euro. A specific point of focus was the European Central Bank’s refusal to follow the rules and keep out of politics. All three founders were good Europeans. They saw integration as necessary but did not support harmonization at any price.

One can agree or disagree with their views, but in a free democracy such movements must be respected. The government in Berlin, headed by Chancellor Angela Merkel, did not. The dominant parties in Germany immediately labeled the AfD “anti-European” and right-wing. The result was that the party changed focus and became more nationalist, while the three founders were forced out. The initial mislabeling became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Marginalized members

The same approach is used to marginalize members of the bloc. In the present debate around the EU’s Covid-19 relief fund and the next seven-year EU budget, the “frugal four” – the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and Denmark – have been singled out as not showing enough European solidarity. Yet they have very valid suggestions for altering the scheme proposed by the Commission, which is backed by Chancellor Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron.

Another issue is the attitude toward Central Europe. Regardless of whether one agrees with the Hungarian and Polish governments, claims that Central European countries are not mature democracies or do not respect the rule of law are hard to swallow, particularly considering all the rules the “mature” Western European democracies have broken.

While the European Union is important as an institution, it cannot claim to be ‘Europe’.

Although the European Parliament has issued a directive for protecting personal data and privacy (the GDPR), it also supports the storage of reams of telecommunications data for security reasons. The policy is supposedly meant to aid the prosecution of crimes, but it also puts everyone in Europe under general suspicion. The European Court of Justice has agreed that such practices are a gross violation of the human right to privacy. That stance was reinforced by a recent ruling that transferring personal data out of the EU requires a guarantee that such rights will be respected. Nevertheless, many EU countries have special legislation that harms and breaches people’s right to privacy.

Other violations of the rule of law are apparent in the so-called “mature” European democracies, like when legislation is unnecessarily retroactive. Rules governing the euro, and the ECB, and regulations meant to ensure fiscal discipline, appear to have become a mere charade.

A village, not a house

The arrogance has another aspect. While the European Union is certainly important as an institution, it cannot claim to be “Europe.” Europe is more than an institution. It is certainly not a nation and must not be. It is a wonderful continent that shares elements of a common heritage – especially Christianity. Yet its main strength is its diversity.

No European country is a world power anymore, so it is important that the heterogeneous medium-sized and small countries on the continent work together to be globally competitive. They showed previously, through the single market and at the beginning of the euro, that this is possible. Harmonization, however, is sapping the EU’s strength.

The trend could destroy Europe’s unique position in the world. Brexit should be a warning. A free Europe is not consistent with a centralized, ever closer union. Less centralism and bureaucracy, and more respect for personal freedom and privacy, is required at the national level as well. The enlargement process of the 1980s and 1990s was based on such values, but they are lacking now, even in the founding member states.

The founders of European integration did not want to build a single European house with the same rules for everybody. Instead, they wanted to develop a European village with many houses that have their own rules, but which work together to advance their common interests. Europe needs integration, not harmonization.