Global oil market dynamics after U.S. intervention in Venezuela

Washington’s move from sanctions to force reshapes Venezuela’s oil outlook and long-term global market dynamics.

In a nutshell

- Sanctions hurt Caracas but failed regime change, prompting escalation

- Low oil production limits global supply shocks, but OPEC stability is at risk

- Recovery hinges on investment, governance and U.S.-China dynamics

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

The recent United States intervention in Venezuela marks a rare military escalation by a major power in an oil-producing country. After years of reliance on sanctions, the move signals a shift from economic pressure to direct action. Given Venezuela’s oil reserves – the largest in the world – and its historical role in global energy markets, the development has prompted renewed scrutiny of the country’s oil sector and its potential implications for global supply, dynamics within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and geopolitics.

Washington’s decision to strike Caracas and forcibly remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro follows more than a decade of progressively tightening international sanctions aimed at weakening Mr. Maduro’s government. Since 2014, Venezuelan government and security officials have faced targeted sanctions for human-rights abuses, corruption and the erosion of democratic institutions. These initial measures, introduced by the U.S. and later joined by the European Union, Canada and Switzerland, focused primarily on individuals and financial transactions.

The most consequential shift occurred in 2019, when Washington imposed comprehensive sanctions on the state national oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), severely restricting its access to American financial markets and hindering its oil trade. The U.S. justified these measures on the grounds that Mr. Maduro’s 2018 reelection lacked democratic legitimacy. Subsequent actions, including measures targeting shipping networks and intermediaries, further constrained Venezuela’s ability to export oil.

The move from sanctions to direct military intervention reflects the limits of economic coercion as a standalone tool.

While sanctions significantly weakened Venezuela’s economy and oil sector, they did not deliver regime change. As seen in other sanctioned producers such as Iran, prolonged economic pressure can erode a state’s ability to operate without producing a decisive political break. The move from sanctions to direct military intervention reflects the limits of economic coercion as a standalone tool.

Meanwhile, years of internal mismanagement and underinvestment, compounded by sanctions, have left Venezuela’s oil industry in a deep and prolonged state of decline. In the short term, the impact of recent developments on global oil markets is likely to remain muted, as there are no quick fixes for restoring Venezuela’s production capacity.

The longer-term implications are far more uncertain, raising fundamental questions about how rapidly production could be rebuilt under new political and investment conditions, should these significantly improve, and what this might mean for global oil markets and key players such as OPEC. It is these longer-term dynamics, rather than immediate supply disruptions, that will ultimately shape Venezuela’s influence on global oil markets.

Venezuela was once an oil giant

Venezuela, a founding member of OPEC, has witnessed significant fluctuations in crude oil production over the past five decades, often driven by above-ground factors such as political interference. Production peaked in 1970 at around 3.75 million barrels per day (mb/d), making Venezuela then the fourth-largest oil producer in the world, behind the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Iran. Thereafter, output declined slightly due to natural field depletion, early OPEC coordination and a cautious approach to investment in new fields.

After the nationalization of the oil industry and the creation of PDVSA in 1976, production initially stabilized but then resumed its decline through the 1980s. Aging infrastructure, underinvestment and a partial loss of technical capabilities in relevant sciences took their toll. In the 1990s, reforms and joint ventures with foreign companies enabled a recovery, with production reaching around 3 mb/d by the late 1990s.

Venezuela’s oil sector under President Hugo Chavez (1999-2013) witnessed a renewed decline, as PDVSA became increasingly politicized and investment suffered. By the early 2010s, output had fallen sharply, reflecting years of underinvestment, loss of technical expertise and operational inefficiencies.

Facts & figures

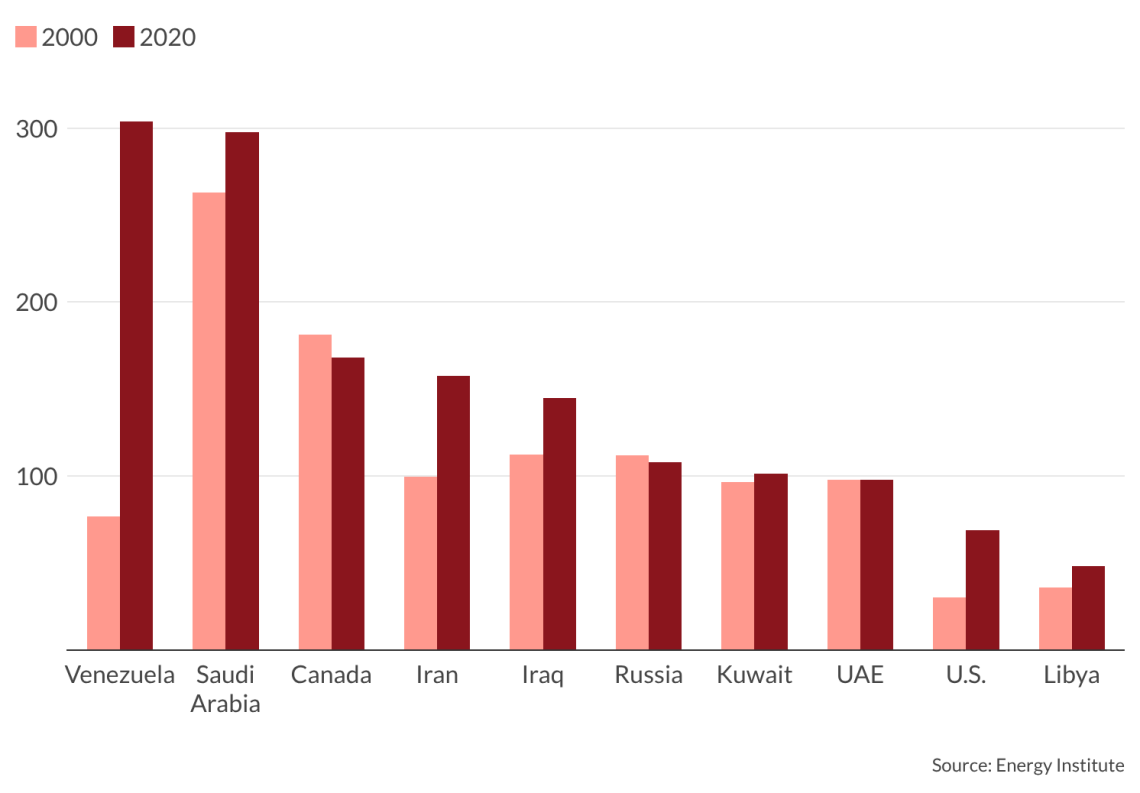

The sanctions implemented since 2014 have further constrained Chavez-era operations. By the time oil-focused sanctions were imposed in 2019, Venezuela’s extraction industry was already in severe structural decline. Sanctions did not cause this collapse, but they exacerbated existing weaknesses by restricting access to finance, technology and export markets. Production fell to an estimated 960,000 b/d in 2024, placing Venezuela 21st among global producers despite having the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

This collapse is historically unprecedented in Venezuela’s oil history. While production had fluctuated before in response to political and market conditions, the recent decline has been deeper, more prolonged and more damaging to institutional and technical know-how than in any previous period. Output today remains far below what the country is geologically capable of producing, underscoring the extent of the sector’s deterioration.

Because of these structural constraints and the prolonged decline in production, Venezuela has struggled to meet OPEC production targets and in recent years has received exemptions to the targets, alongside other heavily sanctioned countries such as Iran and Libya.

Production could eventually be restored if substantial investment begins to flow. U.S. President Donald Trump has recently stated that U.S. oil companies will “go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure … and start making money for the country.” However, key questions remain: To what levels could production realistically recover, and over what time frame? Decades of underinvestment, institutional erosion and sanctions suggest that even with new capital, restoration will be gradual and Venezuela’s future role in global oil markets will depend as much on these practical constraints as on geopolitical developments.

Facts & figures

Venezuelan fossil fuel assets

- Venezuela is the second-largest oil producer in Latin America, after Brazil, and the eighth-largest producer within OPEC, just ahead of the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

- Venezuelan oil exports have grown in recent years, but remain well below the most recent peak of 2 mb/d reached in 2015.

- Oil is vital to Venezuela’s economy and government: In recent years, oil export revenues have financed almost two-thirds of the national budget, with an estimated 58% share in 2024.

- Chevron does not pay cash to PDVSA or the government. Revenues are used to cover operating costs, effectively repaying Chevron in oil for expenses it previously assumed after PDVSA failed to meet its joint-venture obligations. The Venezuelan state receives no new budgetary revenue from the American company, and the temporary license can be revoked by Washington if political conditions deteriorate.

- Venezuela also sits on the seventh-largest proven natural gas reserves in the world, after Russia, Iran, Qatar, Turkmenistan, the U.S. and China. It is the world’s 23rd largest gas producer.

A comparison can be drawn with Iraq, another major oil producer that experienced years of sanctions and conflict before reopening its oil sector to international companies in 2009. Iraq’s production eventually recovered and even surpassed its historical peak once international companies returned and investment resumed. However, that recovery took many years and followed a shorter period of production collapse than Venezuela has experienced. Equally important, it happened when oil prices were much higher than the levels we are seeing today and when the U.S. shale revolution was barely recognized.

Venezuela’s decline has been longer-lasting and more severe, suggesting that even under improved political and investment conditions, any recovery in production is likely to be gradual rather than rapid, especially in today’s market circumstances.

Oil trade and prospects

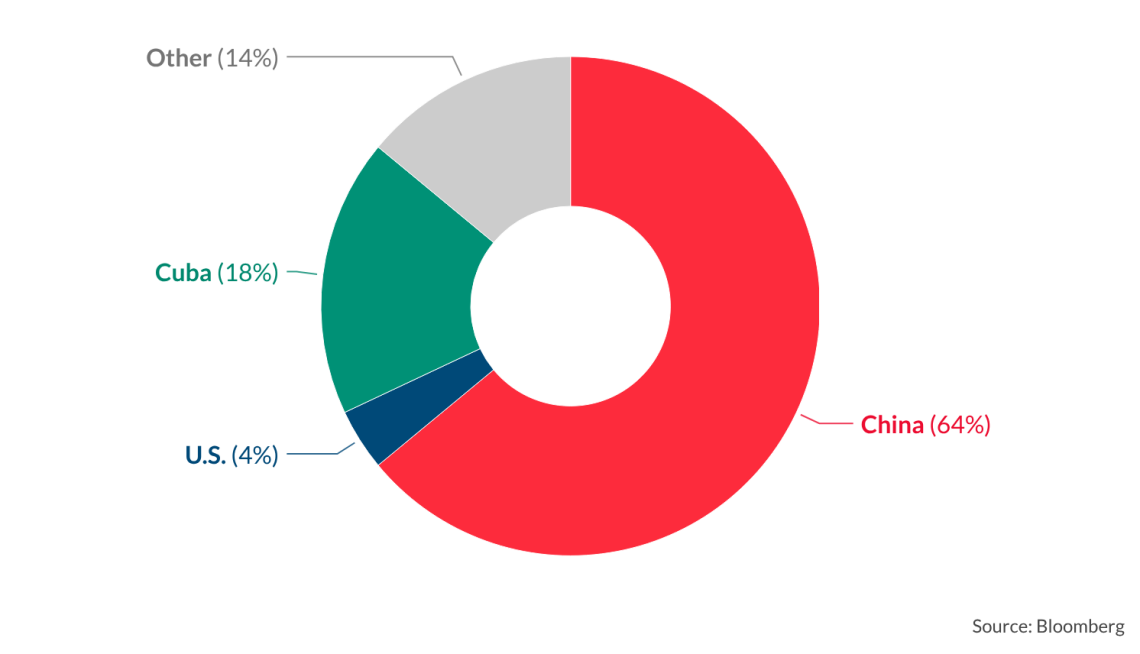

Venezuela’s oil exports have undergone dramatic shifts over the past decade, shaped by sanctions, geopolitics and changes in demand. Historically, the U.S. was the dominant importer, particularly of Venezuela’s heavy crude suited to American Gulf Coast refiners, while China and other Asian buyers played a smaller role. In 2017, the U.S. imported around 41 percent of Venezuelan oil exports, compared with 25 percent for China.

By 2025 (January-November), the balance had shifted dramatically: China received nearly 64 percent of Venezuelan oil exports, while the U.S. share fell to about 4 percent.

China would be affected by a potential U.S.-led reopening of Venezuelan oil production and redirecting exports to North America. Beijing has become Venezuela’s lifeline in recent years, purchasing heavily discounted barrels that many other buyers avoid. A shift toward American investment and production would reduce China’s access to these cheap barrels and weaken its influence in Caracas.

That said, China is not critically dependent on Venezuelan oil; it has a diversified import portfolio and multiple alternative suppliers, including the Persian Gulf. In a well-supplied global market, any increase in Venezuelan output under U.S. direction could also put downward pressure on oil prices, mitigating the commercial impact for China.

American companies have a built-in advantage in Venezuela, having operated in the country before Chavez’s policies and retaining institutional knowledge of its infrastructure and operations. Chevron is still present and is the only U.S. oil major operating in Venezuela. The Houston-based company holds a license issued by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), allowing it to continue limited joint operations with state oil company PDVSA. Under the terms of this license, Chevron can produce oil from existing joint ventures and export it, primarily to U.S. Gulf Coast refineries, but it cannot launch new projects or significantly expand production. Current output under the license is estimated at around 100,000 barrels per day.

However, a recovery will not be straightforward. Challenges include poor governance and a lack of transparency within PDVSA such as in sharing data with partners, a limited understanding of the current state of the oil fields and production infrastructure, and the high carbon intensity of Venezuela’s heavy crude. Legal and regulatory uncertainties also loom large: It is unclear how quickly new laws or frameworks will be enacted to facilitate foreign participation, and how favorable the terms will be. Even with experience and an existing American presence, these factors mean that ramping up production will take a measured pace.

Facts & figures

U.S. Gulf Coast refiners, configured to process heavy, high-carbon crude, stand to benefit if Venezuelan production increases and prices ease. Their refineries are specifically designed for this type of crude, which is not easily interchangeable with lighter oils, giving them a direct commercial advantage. The scale and timing of these benefits, however, will depend on how quickly investment translates into actual production.

Muted market response

Despite the dramatic geopolitical developments, the immediate impact on global oil markets has remained relatively muted. Venezuela currently produces less than 1 mb/d, under 1 percent of global supply, an amount too small to move markets in a meaningful way. Oil prices fell more than 18 percent in 2025 amid oversupply concerns, and even a full return of Venezuelan barrels would not flood the market. Years of underinvestment, infrastructure decay and loss of human capital mean that production cannot rebound rapidly, even with the recent political changes or potential easing of sanctions.

OPEC’s first meeting of this year on January 4, one day after the military action in Venezuela, underscored the fragile situation. While the group emphasized that global economic conditions remain stable, inventories are low and market fundamentals are generally healthy, it also highlighted the need for a “cautious approach,” leaving all options open. Although the statement did not mention Venezuela explicitly, this prudence can reasonably be linked to the added geopolitical uncertainty following the U.S. intervention.

Read more by energy economist Carole Nakhle

- U.S. oil production: A peak in sight

- What is holding up progress on small modular reactors?

- Iran’s oil sector: Strategic presence, diminished influence

Other sanctioned producers, notably Iran and Russia, are likely monitoring the situation carefully, assessing to what extent sanctions and political pressure could be increased. While these developments do not immediately alter supply-demand balances, they introduce questions about future Venezuelan oil flows and potential longer-term market dynamics.

Looking further ahead, Venezuela’s post-crisis trajectory could have more significant implications. Despite being a founding member of OPEC, the country might face pressure to leave the producers’ group to attract foreign investment and expand production. And while a gradual increase in output could put downward pressure on prices, the more consequential factor is the geopolitical signal sent to other producers about Washington’s willingness to intervene and reshape production dynamics.

Scenarios

In either of two feasible scenarios, Venezuela may be forced to leave OPEC under U.S. pressure, depending on how geopolitical and market pressures evolve.

Most likely: Venezuela’s gradual reintegration to global markets

Venezuela’s oil sector begins to recover gradually, contingent on necessary policy reforms and sustained sanctions relief. Production increases at a moderate pace, allowing Venezuela to regain market share over time, particularly with U.S. Gulf Coast refiners.

As Venezuela’s production ramps up, its increasing contribution to supply will not disrupt market dynamics in the short term; though the additional barrels can still put limited downward pressure on prices.

Venezuela will face tensions within OPEC. The country’s desire to reclaim market share could lead it to prioritize national interests over OPEC’s framework and goals, testing the group’s cohesion over time.

Less likely: Rapid recovery amid wave of investment

Venezuela’s oil sector recovers rapidly, with significant foreign investment. The country would quickly regain market share. The sudden influx of Venezuelan crude could disrupt global supply dynamics. While the market may initially absorb the increased supply, a rapid surge could lead to price volatility, particularly if demand does not keep pace with the new production levels.

The rapid recovery would generate stronger tensions within OPEC. Venezuela’s ambitions could make quota compliance difficult, heightening internal discord and undermining the group’s ability to manage the oil market effectively.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.