Milei’s economic policy in Argentina

Argentina’s President Milei is battling stagflation with bold reforms but faces hurdles in maintaining disinflation and fiscal balance.

In a nutshell

- Milei’s rise was driven by antiestablishment, free-market rhetoric

- Fiscal adjustments include short-term cuts, not structural reforms

- Exchange rate policies struggle with rapid devaluation

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

For almost two years since taking office, Argentine President Javier Milei has ridden a wave of optimism, promising a bold economic turnaround. As a far-right libertarian, he tackled decades of stagnation and runaway triple-digit inflation with sweeping reforms. Although many have welcomed the slowdown in inflation, significant cuts in public spending have triggered protests from retirees, teachers and doctors. Additionally, his high-stakes currency maneuvers have faltered, jeopardizing his agenda just as midterm elections loom on October 26.

To fully evaluate President Milei’s economic policies and their prospects, we must first understand the context of his rise to power.

Milei’s rapid ascent

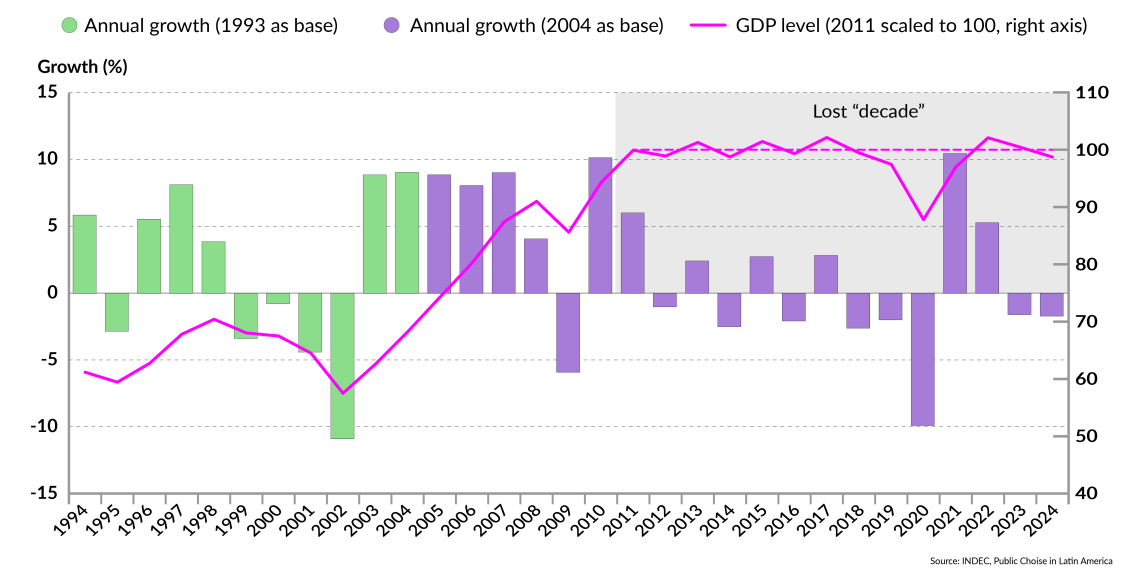

Argentina’s economy had stagnated since 2011, with inflation steadily rising since 2007. The left-leaning Kirchnerist movement held power from May 2003, with only a brief interruption when Mauricio Macri’s Cambiemos coalition was in office from 2016 to 2019. (The Kirchnerist movement, also known as Kirchnerism, is a political ideology associated with Nestor Kirchner, who served as president of Argentina from 2003 to 2007, and his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who was president from 2007 to 2015.) After a currency crisis, Alberto Fernandez’s presidency marked the return of Kirchnerism to power in 2020.

By the time President Milei took office in December 2023, Argentina had endured 20 years of left-leaning populist rule, interrupted only by President Macri’s brief and unsuccessful term. An entire generation of Argentines has known nothing but stagnation, rising inflation, social fracture and diminished hope – even after trying a non-populist alternative.

Facts & figures

Argentina’s GDP growth

This created a unique opportunity for a political outsider like Mr. Milei, an economist who rapidly ascended to the presidency. His meteoric rise was driven primarily by an antiestablishment message, coupled with free-market rhetoric focused on balanced budgets and market deregulation. With a strong personality and an image of integrity, Mr. Milei set himself apart from the questionable reputations of typical politicians.

As a trained economist, he seemed well-qualified to address Argentina’s economic problems. Much of the public’s renewed attention to fiscal deficits can be attributed to his influence.

The context of Mr. Milei’s presidency set clear expectations for his administration: fix the economy and maintain honesty while avoiding the behaviors of those he came to replace. President Milei’s plan to address the economic challenges rests on two pillars: reducing inflation through monetary policy and achieving a balanced budget through fiscal policy.

Monetary policy under the Milei administration

President Milei’s monetary policy began with addressing high inflation as a priority, which required a strong and credible shock. Two decisions established the foundation for the new monetary regime.

First, a necessary devaluation of the Argentine peso took it from 400 to 800 per United States dollar in December 2023. This made Argentine exports cheaper but increased costs for imported goods like food and fuel.

Second, the government reintroduced Argentina’s traditional strategy of controlling inflation through a managed exchange rate, specifically implementing a “crawling peg” that adjusts the peso by 2 percent each month. This system gradually modifies the currency’s value in small, predetermined increments, aiming to stabilize prices by regulating how quickly the peso depreciates against the dollar. However, with the lowest inflation rate in 2023 at 5 percent and the massive currency devaluation, the 2 percent crawling peg may not have been the most effective choice. In fact, any competitive edge gained from the peso’s devaluation in December 2023 was lost by October 2024.

Facing growing pressure on the exchange rate, in June 2024, Milei’s team launched Phase 2 of its economic stabilization plan. This phase differed little from Phase 1; it maintained the 2 percent monthly crawling peg while also promising to freeze the broad money supply (base money – cash, inherited central bank liabilities and treasury deposits) in the economy. Since the currency in circulation had increased by 66.8 percent by June, Phase 2 aimed to instill confidence in the economic plan by assuring tighter control over monetary expansion.

In February, Phase 2 was adjusted – not by increasing the crawling peg rate, but by halving it to 1 percent per month. The Central Bank of Argentina’s rationale was that inflation continued to fall. However, the peso had already appreciated significantly by then. The reduction of the crawling rate conflicted with the still appreciating peso. This inconsistency led to a major revision of monetary policy with the introduction of Phase 3 in April.

With a new agreement from the International Monetary Fund to strengthen central bank reserves, Argentina replaced the crawling peg with a new exchange rate system that, in principle, lets the peso float (or fluctuate) freely between lower and upper bounds. As long as the peso’s value remained within these limits, the central bank was authorized to buy dollars to build its reserves but was not allowed to intervene by selling them, except if the exchange rate hit the upper limit. Phase 3 did not deter the government from using the exchange rate to control inflation. Instead of intervening directly in the spot market, it influenced the situation indirectly in the futures market.

The exchange rate remains the most significant challenge in President Milei’s monetary policy. A central bank that cannot or does not want to accumulate reserves, combined with growing market expectations of a new devaluation, places additional strain on one of the main anchors of Mr. Milei’s economic strategy.

While chainsaw cuts can produce cyclical budget surpluses, reforms are needed to deliver a structurally balanced budget.

Argentina’s disinflation: Separating reality from perception

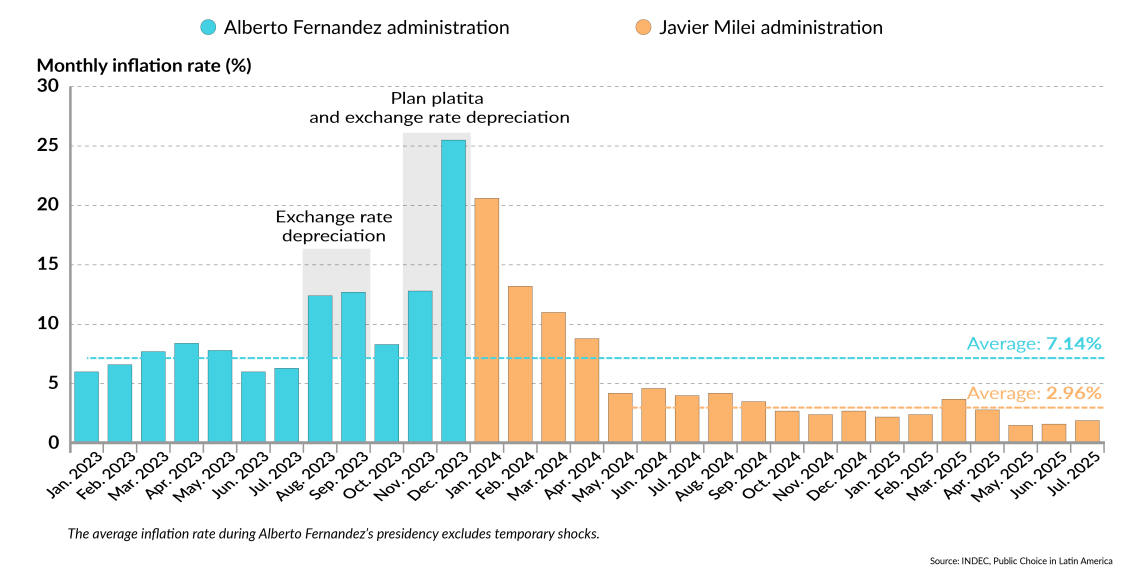

Since taking office, Mr. Milei’s policies have led to a significant reduction in inflation, which had soared to a staggering monthly rate of 25 percent in December 2023. Now, at just 1.9 percent, the monthly rate stands among the lowest levels recorded since April 2020. How, then, should we interpret Argentina’s disinflation process? (Disinflation is a decrease in the rate of inflation, where prices continue to rise but at a slower pace, and which may or may not be a temporary phenomenon.)

This requires understanding the different factors driving disinflation at various points in time.

The first factor involves temporary shocks from 2023 that would eventually fade. Beyond a mid-2023 devaluation, two other events occurred near the change of government. One of these shocks introduced was the plan platita (pocket money plan), a strategy employed by the Kirchnerist government to print money in the lead-up to elections to buy electoral favors. This monetary shock was not a permanent fix; instead, it had only a fleeting impact on inflation. The second event was the December devaluation. When these temporary factors are excluded from the analysis, the average inflation rate for 2023 stands at 7.14 percent. Therefore, the 25 percent inflation rate observed in December 2023 should not be viewed as an indicator of high inflation, but rather as a representation of a normal inflation rate without temporary shocks.

Facts & figures

Monthly inflation rates: Fernandez era vs. Milei reforms

A second reason for disinflation, which gained prominence as temporary shocks subsided, was the economy’s rapid recovery after the sharp decline caused by the December 2023 devaluation. However, this rebound has not translated into sustainable growth, as major structural reforms have yet to be implemented. Aggregate economic activity remains within the range observed since 2011 (excluding the Covid-19 years).

The third factor is monetary tightening, especially the astronomically high real interest rates observed more recently.

While no one disputes the decline in inflation, understanding its causes offers a clearer view of monetary policy effectiveness and its sustainability. For instance, how long can the exchange rate avoid another devaluation, and when will the government prioritize lower real interest rates over higher inflation? This would not be the first time a reduction in the inflation rate has reversed, as recently observed under Mr. Macri’s government.

Fiscal policy

Like monetary policy, fiscal policy is more complex than it initially appears. President Milei quickly achieved a fiscal surplus, but how? In 2024, Argentina achieved its first budget surplus in over a decade. Much of the adjustment came from real cuts to pension and retirement funds, delayed payments to providers, freezing public investment and deferred debt obligations.

Many of these decisions make sense. When a new CEO takes over a bankrupt company, it is expected that payments will be postponed. However, it is important not to confuse cyclical (temporary) surpluses with a structurally balanced budget. The latter is evaluated based on the present value of projected future budget results, and this is where meaningful change is lacking. Postponing payments to provinces or adjusting retiree benefits incurs costs that can be easily reversed if it becomes politically convenient during election periods or when a new Peronist government takes office. For example, just in the past month, the Argentine Congress has demonstrated its political power to dictate government expenditures, as is its prerogative.

Another growing concern is the central bank’s strategy of eliminating its liabilities, which were replaced by new treasury bonds. Some of these bonds add their interest payments (coupons) to the principal balance instead of paying them out, allowing the debt to grow over time. These coupons are not recorded in budget reports (neither on a cash-flow nor an accrued basis).

Initially representing approximately 0.25 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), these bonds are now estimated to account for more than 2 percent of GDP. These are peso-denominated bonds with limited demand from investors. Ensuring indefinite rollover (refinancing of the debt) is unrealistic, especially when interest rates are outpacing growth in a stagnant or potentially recessionary economy. Where will the government find another 2 percent of GDP in expense cuts?

Read more by Nicolas Cachanosky

- The economic cost of a U.S. manufacturing renaissance

- The divergent immigration challenges in the U.S. and Europe

- Why Argentina might switch to the dollar

Unfortunately, this is where the popular chainsaw rhetoric meets reality. While chainsaw cuts can produce cyclical budget surpluses, reforms are needed to deliver a structurally balanced budget. This remains a pending issue in Argentina. Although there are hopes that President Milei’s administration intends to pursue these reforms, the reality is that major structural changes are still required.

Within this scenario, congressional opposition has demonstrated its power to pass laws with spending implications. Ultimately, managing the budget is a legislative responsibility, while the president’s role is to execute the budget approved by Congress. The loss of political capital adds further uncertainty to Argentina’s future fiscal outlook.

While the economic plan is beginning to show its limitations, President Milei’s administration has also faced allegations of corruption scandals. The $Libra affair, in which Mr. Milei promoted a cryptocurrency that quickly failed, has raised serious concerns. Additionally, recently disclosed recordings have implicated his sister, Karina Milei, who serves as the General Secretary of the presidency, in questionable purchasing practices involving medication. Both incidents have the potential to damage the government’s ability to rebuild credibility.

These corruption allegations, whether substantiated or not, could create an additional burden as the administration seeks to generate the positive confidence shock necessary for economic recovery.

Scenarios

Likely: A new economic plan is put in place

The blow to political capital necessitates a major monetary policy shock to rebuild market credibility. Phase 2 essentially continued from Phase 1 without making real changes. The government undermined the essence of Phase 3 by indirectly interfering in the exchange rate market. With a credibility issue looming and the midterm elections approaching fast, there is a strong possibility of unveiling a new economic plan.

Somewhat likely: Economic plan continues with revisions

If the current plan remains but is revised, the most probable changes would be a depreciation of the exchange rate and the removal or recalibration of the currency bands. Without access to international markets, the need to build reserves might lead to a new exchange rate depreciation.

Very unlikely: Economic plan continues unchanged

Beyond the increasing tensions discussed above, the government needs to accumulate U.S. dollars to service its debt. The central bank has not accumulated reserves, and the treasury has recently been selling dollars in the spot market to control the exchange rate. The unexpected importance of Kirchnerist performance in the midterm elections in Buenos Aires province adds political pressure for change.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.