Timor-Leste charts its post-oil future

Timor-Leste, a small nation heavily reliant on oil, finds itself in a delicate position, grappling with economic downturns and dwindling resources.

In a nutshell

- Oil production declines threaten Timor-Leste’s economic stability

- Youth unemployment and poverty remain deeply entrenched

- Political elites criticized for lack of economic diversification

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

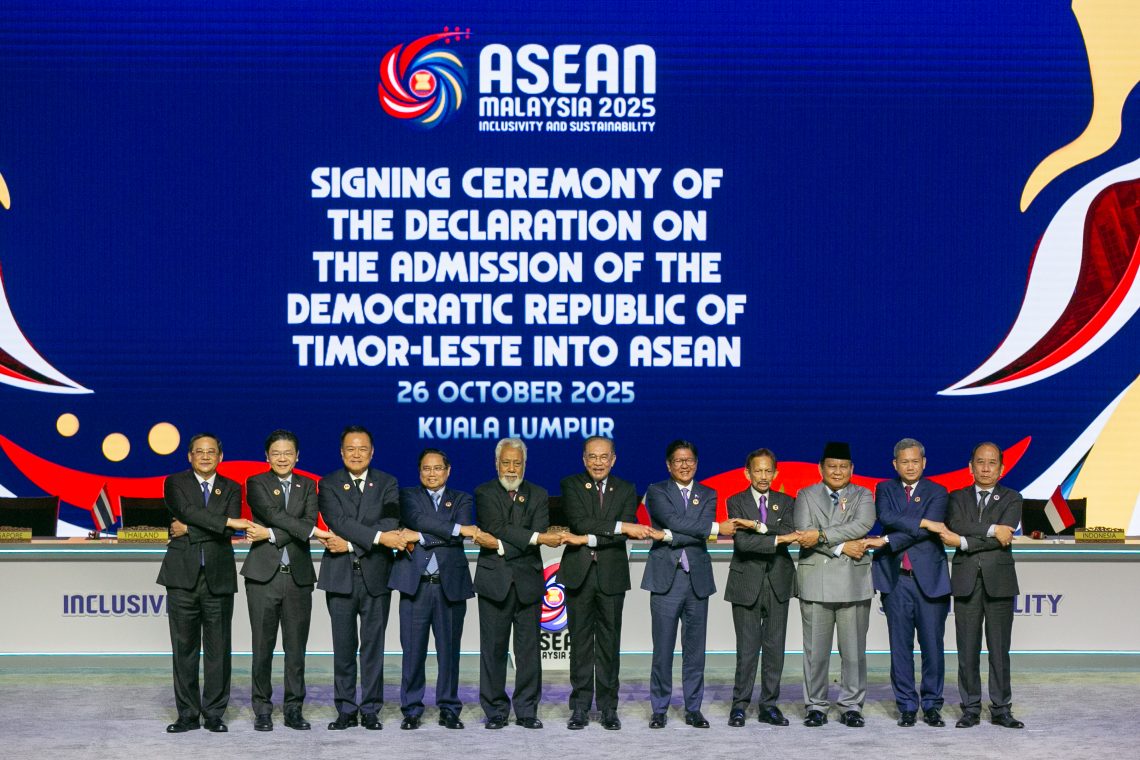

Timor-Leste, also known as East Timor, is one of the world’s youngest countries. As of October this year, it has officially become the newest member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), bringing to fruition a 13-year journey and signifying the nation’s full integration into Southeast Asia’s political and economic landscape.

The island nation has endured a turbulent history: centuries of colonial domination, a brutal 24-year Indonesian occupation and, since independence, a heavy dependence on oil wealth that has shaped both its fortunes and its vulnerabilities.

The Portuguese connection

Portuguese explorers, traders and missionaries first reached the remote island of Timor between 1512 and 1515. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the island became a stage for conflict among the Portuguese, the Dutch and local microkingdoms vying for control of the territory. In 1859, the Treaty of Lisbon was signed, dividing Timor: East Timor (Portuguese Timor) was assigned to Portugal, while West Timor was assigned to the Netherlands. West Timor has been part of Indonesia since 1949.

Throughout much of the colonial period, Portuguese Timor was not governed directly from Lisbon but was administered through its other Asian territories – first from Goa (in India) and at times from Macau (in China). Direct rule from the Portuguese capital only became the norm in the late 19th century. Timor-Leste became a site where various Portuguese governments, across different political regimes, deported their political opponents.

During World War II, Portugal chose to remain neutral, but as Australian and Dutch forces took control of the island, the Japanese also invaded and occupied Timor-Leste (East Timor). This invasion sparked a wave of resistance, uniting both the Portuguese and the local inhabitants. After the war, Timor-Leste returned to Portuguese rule, and the situation remained fairly calm until the military coup in Lisbon on April 25, 1974.

Facts & figures

Timor-Leste

Indonesian invasion and occupation

On November 28, 1975, Fretilin (the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor), a leftist political-military movement, declared the independence of the Democratic Republic of East Timor.

Under General Suharto, the Indonesian military took a hardline stance against communism, launching a ruthless purge of suspected communists following a plot that led to the deaths of several military generals. They were determined to eliminate any communist presence near their borders. In response to Fretilin’s growing influence, Indonesia launched an invasion in early December 1975, establishing a regime of occupation and annexation that would last more than two decades, continuing until the collapse of Suharto’s dictatorship. Throughout this period, the local population faced widespread violence, epitomized by the tragic Dili (or Santa Cruz) Massacre in 1991, where hundreds of protesters were killed by Indonesian forces.

During the Indonesian occupation, Portuguese political forces – spanning the entire spectrum from the far left to the conservative right – remained united in defending Timor-Leste’s distinct identity and its right to self-determination.

This broad-based support helped keep the issue alive on the global stage and contributed to growing international pressure on Indonesia. The culmination came in 1996 when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to two leading figures of the resistance: Roman Catholic Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo and Jose Ramos-Horta, the diplomatic spokesman for Fretilin and later Timor-Leste’s first foreign minister and the current president.

After Suharto’s fall in 1998, a United Nations-supervised referendum in 1999 delivered a 78.5 percent vote in favor of independence. Pro-Indonesian militias responded with scorched-earth violence, displacing hundreds of thousands and prompting an Australian-led international intervention. In 2002, following a period of UN-led administration and transitional governance, the country officially achieved independence, becoming the first new sovereign nation of the 21st century. It established a semi-presidential system in which the president is elected by popular vote, while the National Parliament appoints the prime minister.

The risks of an oil-dependent economy

Independence, however, brought new challenges. Timor-Leste is now ASEAN’s poorest member: 42 percent of its people live below the national poverty line, chronic malnutrition affects nearly half of all children under five and almost two-thirds of its 1.4 million citizens are under 30, creating enormous pressure for jobs and services.

Timor-Leste’s economy remains heavily dependent on oil and gas revenues. But it is currently facing formidable economic hurdles as it seeks to diversify and build sustainable growth beyond its depleting offshore fields. The output has dropped to under 50,000 barrels per day and is continuing to decline. The Bayu-Undan field, which peaked at 114,000 barrels per day in 2019 and had been the backbone of Timor-Leste’s oil revenue for two decades, permanently ceased production in June of this year.

This could have been even more disastrous were it not for the government’s prudent decision in 2005 to establish the Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund. This sovereign wealth fund manages surplus revenues from the oil and gas sector, and as of October, its assets are valued at $18.8 billion.

Navigating a neighborhood of giants

One of the greatest concerns for a small country surrounded by bigger players is managing its foreign relations and strategic alignments.

Despite the traumatic past, Timor-Leste has built warm relations with Indonesia, especially on the economic front. The fall of Suharto’s dictatorship marked a pivotal moment in the struggle for Timorese independence. Suharto’s immediate successor, President B.J. Habibie, laid the foundation for improved relations. Efforts toward reconciliation were pursued through the Commission of Truth and Friendship, which operated until 2008.

Dili’s political elite took a pragmatic approach, choosing not to dwell on revenge toward their powerful neighbor. Observers note that this realism has benefited both nations: Timor-Leste could not afford a conflict with Indonesia, while Indonesia had a vested interest in maintaining Timor-Leste’s political and economic stability. Timor-Leste’s long-awaited accession to ASEAN largely depended on Indonesia’s persistent diplomacy, with Jakarta actively lobbying other member states to gain consensus. Singapore initially opposed the bid, arguing that Timor-Leste was not yet ready to meet the institutional and administrative demands of full ASEAN membership.

To the south, relations with Australia have followed an equally complex but ultimately positive arc. Back in 1975, during the Cold War, both Canberra and Washington initially supported Indonesia’s invasion due to fears of a potential communist regime on the island. After the post-election turmoil and violence in 1999, Australia led the International Force East Timor mission and deployed 5,500 troops to support the transition.

Since independence, Australia has been Timor-Leste’s largest bilateral donor and economic partner. The trade and investment ties between Australia and Timor-Leste are quite significant today – two-way merchandise trade between the countries reached $288 million in 2024.

Beyond its immediate neighbors, Dili has also cultivated ties with larger global powers, such as China. In fact, China was the first nation to officially recognize Timor-Leste on May 20, 2002, and the first to enter into an economic and technical cooperation agreement with the country. Before this, Beijing had already acknowledged at the UN the right of Portuguese Timor to self-determination.

In addition to these political signals, China has undertaken major infrastructure projects in Timor-Leste, including upgrades to the power grid. Chinese firms played a key role in constructing the Suai Highway (Phase I) and were also involved in building Tibar Bay Port, along with several new government structures, such as ministerial offices and various agriculture-related developments. President Ramos-Horta has shown a desire for deeper cooperation with China, endorsing the Belt and Road Initiative. He also expressed support for a peaceful reunification of Taiwan with the mainland, a topic that remains politically sensitive.

The United States maintains a modest but steady presence in Timor-Leste, offering security training, aid programs and diplomatic support.

Read more on Southeast Asia

- Southeast Asia’s economic model at risk due to U.S. tariffs

- The significance of ASEAN as major powers recalibrate

- Prabowo’s policies spark both hope and concern in Indonesia

The hope of Greater Sunrise

The key to a sustainable economic future for Timor-Leste lies primarily in collaboration with Australia, particularly through the joint development of the Greater Sunrise gas field. Located in the Timor Sea, the field is 150 kilometers south of Timor-Leste and 450 kilometers northwest of Darwin, Australia. Maritime agreements between the two nations, in 2018 and 2024, have paved the way for a fair distribution of costs and revenues derived from these resources.

The Greater Sunrise exploration project features an ownership structure that includes Timor GAP, the national energy company of Timor-Leste, which holds a 56.56 percent majority stake. Australian company Woodside Energy owns 33.44 percent, while Japanese firm Osaka Gas holds 10 percent. This gas field is estimated to contain around 5 trillion cubic feet of dry gas, and the overall value of the project is between $50 billion and $75 billion.

Facts & figures

Greater Sunrise gas field: Timor-Leste’s economic lifeline

In November, Timor-Leste formally invited ASEAN investors to participate in developing the Greater Sunrise gas field, emphasizing that gas processing and pipeline construction should occur within the country to maximize economic benefits and job creation.

The hope for the country’s future lies in this project, alongside efforts to diversify the economy and restore agricultural production. This includes prioritizing investments in sustainable agriculture, such as high-value crops like coffee, vanilla and coconut products, as well as building resilient food systems. There is also a focus on ecotourism and the emerging “blue economy,” which emphasizes the sustainable development of ocean and coastal resources. Without these initiatives, the Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund is projected to run out in around 10 years.

Scenarios

Likely: Slow transition beyond oil

The primary challenges facing Timor-Leste revolve around its economic future, which is crucial for the nation-building process. Given the issues and risks associated with the local petro-economy, the best course of action is centered on one key concept: diversification. This diversification, which includes investments in agriculture, ecotourism and the blue economy, can be financed by the remaining substantial resources of the Petroleum Fund. Additionally, collaborating with Australian and Japanese partners on the development of the Greater Sunrise gas field can further bolster these initiatives.

This is the more likely scenario, as all forecasts indicate the Petroleum Fund will run dry by 2038. Its performance might improve with the recent integration into ASEAN, but maintaining a sound fiscal policy will be essential. This means encouraging private business investment rather than relying on subsidies, and providing stronger guarantees for investors. Fortunately, the major political parties in Timor-Leste seem to recognize these realities.

Unlikely: Return to petro-state dependency and failed-state risk

The unlikely scenario stems from neglect of the diversification strategy, particularly in terms of substantial investments in agriculture. The main local crops include coffee, rice, corn, cacao and cinnamon. The mountainous terrain limits the amount of arable, fertile land available. A significant portion of the population relies on subsistence farming, which puts food security in a fragile position.

In an article published in August 2023 in the Australian Financial Review, James Curran, a professor at the University of Sydney, warned that the nation was “on the brink of becoming a failed state.” He attributed the risk to the quality of the “stubborn and entrenched elites,” who were living off a “dwindling sovereign wealth fund” and fixated on “new oil revenues” while dismissing the necessity for an alternative “Plan B.” At that time, Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao stated that Timor-Leste would not consider joining ASEAN until the Myanmar crisis was resolved.

With a strong partnership between Timor-Leste and Australia on the Greater Sunrise project, coupled with the country’s successful integration into ASEAN, the once-dire predictions from 2023 now appear outdated. Prime Minister Gusmao – leader of the largest party, the National Congress for the Reconstruction of Timor-Leste (CNRT), which holds 31 seats – and President Ramos-Horta – an independent backed by the CNRT in his 2022 election – have demonstrated a willingness to cooperate despite past rivalries. Together with Fretilin (19 seats), the second-largest party now in opposition, the political leadership shows a shared commitment to addressing the country’s issues.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.