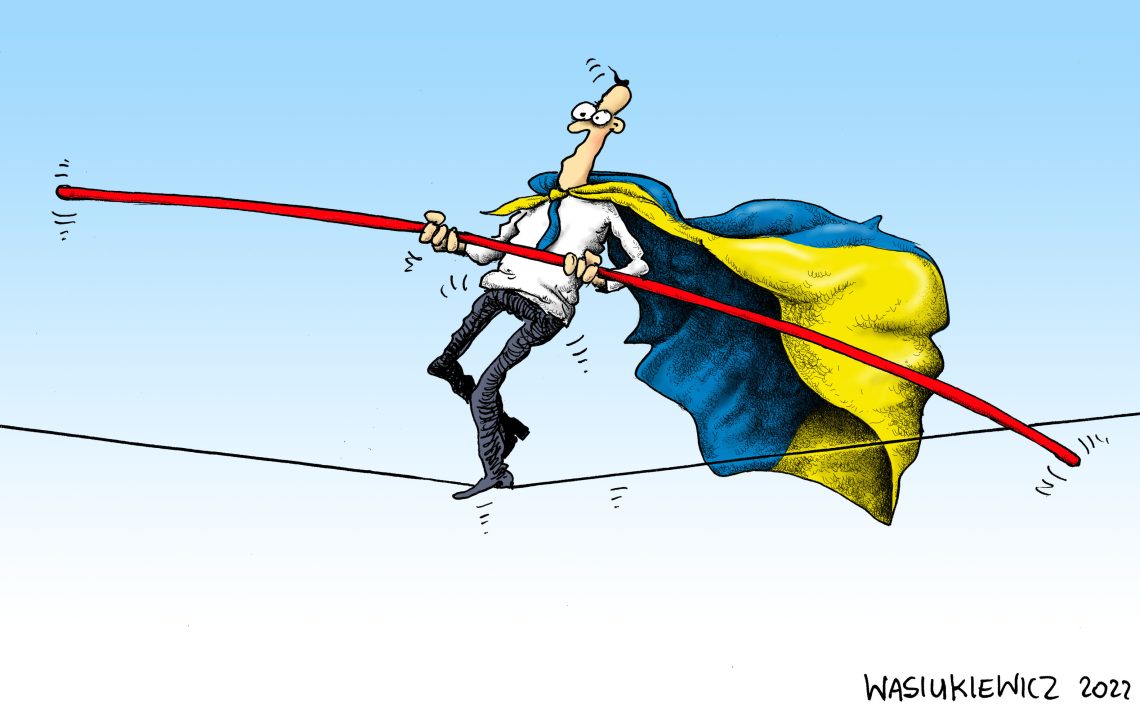

Staying coolheaded over Ukraine

With Russian troops at the Ukrainian border, NATO appears to have regrouped, but several challenges lie ahead before a solution can be found. Most importantly, Kyiv should be an active player in further negotiations.

In November 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron declared NATO “brain-dead.” At the time, his observation seemed accurate – even though one might question the wisdom of such a comment coming from the head of an important member state.

However, with the Ukraine crisis, NATO appears to have awoken from its coma. The alliance and most of its member states have declared their support for Ukraine and want to keep its borders intact. They have delivered materiel, trained personnel and pledged to retaliate with harsh sanctions (including from the EU) should Moscow take its troops over the border. However, these threats are made somewhat weaker by declarations that there will be no military response from NATO.

Give Ukraine a voice

After Russia put some 100,000 troops on the Ukrainian border in late 2021, a flurry of military and diplomatic activity ensued. So far both Russia and the Western alliance have had some successes.

First and foremost, the Kremlin managed to get the United States to the negotiating table, as well as NATO. There were high-level meetings between presidents and the German Minister of Foreign Affairs traveled to Moscow. All this boosted the standing of the Russian president. Another potentially unintended victory for the Kremlin was to neutralize Germany within the alliance.

A bizarre aspect of the situation is that there is little talk of Ukraine itself.

The West, meanwhile, has managed to reinvigorate NATO. Europe has been reminded that not only the U.S. but also the United Kingdom and Turkey, play an important role in security matters.

Still, nervousness runs extremely high in the West. Any Russian action near the border leads to rumors of an imminent attack. This plays into Russia’s hands, as it creates insecurity and fear among the population in Ukraine and Central Europe.

A bizarre aspect of the situation is that there is little talk of Ukraine itself and Kyiv’s interests, which are in fact at the heart of the matter. The Ukrainian army is on high alert and also informal (guerilla) activities appear to be underway. President Volodymyr Zelenskiy has asked his own people, and especially Western strategists and politicians, not to panic.

It cannot be in Russia’s interest to invade Ukraine and engage in a long war, in the style of Iraq or Afghanistan, in its own neighborhood. Some inhabitants of eastern Ukraine may harbor sympathies for the Russians, but most Ukrainians do not. A guerrilla war is the last thing any country wants. Hopefully, the government in Kyiv will stay coolheaded, even though it wants and needs Western support.

Moscow was angling for negotiations, and it is likely that it also hoped for the official recognition of Crimea as part of Russia (tacitly this is already the case). It also wants to keep Ukraine out of NATO. So far, the Kremlin has not received any such guarantees.

President Putin is not known to take excessive risks. If the West presents a united front, it could help create a fair discussion between Kyiv and Moscow. But Ukraine would need to have a voice of its own in these negotiations, and not be discussed in the third person – as is too frequently the case.