Turkey’s push for greater influence in Central Asia

Turkey sees an opportunity to build its influence in the Turkic nations of Central Asia. It is an attractive strategic move for Ankara – but it is not without dangers, as Turkey is certain to butt heads with other powers in the region, namely China, Russia and Iran.

In a nutshell

- Turkey is gaining new access to Central Asia

- Ankara's alliance with Azerbaijan is deepening

- Russia and Iran stand to lose out

Turkey has long-standing ambitions to enhance its influence among the Turkic peoples of Central Asia. Seeking to spread its vision of pan-Turkism, it has sponsored programs of cultural exchange, accepted large numbers of guest workers from the region and promoted trade. Yet these initiatives have not brought Turkey closer to its goals.

Changing focus

Russia has used its historical role as regional hegemon to thwart Turkish influence. China’s rise has reduced the playing field for new entrants even further. Iran, keen on developing its own trade with Central Asia, has hampered Turkey’s plans to do the same. However, two recent developments suggest the tide may now be turning in Turkey’s favor.

One is Turkey’s deepening alliance with Azerbaijan. The latter’s rout of Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh war last year opened new opportunities for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to project geopolitical influence into Central Asia. Turkey’s robust military support for the Azeri offensive was a decisive factor. Now, Yerevan must accept a corridor across its territory, from the southern part of Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan, an Azeri exclave landlocked between Armenia and Iran. The route gives Turkey a clear path to the Caspian Sea, allowing Ankara to break free from dependence on Iran and mount a more forceful challenge to Russia.

The new realities in the Middle East will likely motivate Ankara to increase its influence in Central Asia.

The other development is the United States-brokered Abraham Accords, which undermine Turkey’s position in the Middle East. Having normalized its ties with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, Israel is heading toward a fundamental transformation in its relations with the Arab world, and could even normalize its relations with Saudi Arabia. These changes are a blow to President Erdogan, who has cultivated an image as a protector of Muslim rights. He has provided support for the Muslim Brotherhood and for Hamas, which has been allowed to hold meetings in Turkey.

The new geopolitical realities in the Middle East will likely motivate Ankara to compensate by increasing its influence in the South Caucasus and in Central Asia. In the words of Huseyin Bagci, head of the Ankara-based Foreign Policy Institute, the “Islamic card and talk of Muslim unity” no longer work and are being replaced by Turkish nationalism.

Energy advantage

The most immediate payoff that Ankara will derive from its alliance with Azerbaijan lies in the field of energy, where improved access to the vast gas reserves in Turkmenistan may help enhance Turkey’s already strengthening position as a regional energy hub. Following three decades of wrangling, in mid-January Baku and Ashgabat finally agreed on joint development of an oil field in the Caspian Sea. Although the new field will not be overly important by itself, the cooperation could open a route to European markets for Turkmen gas.

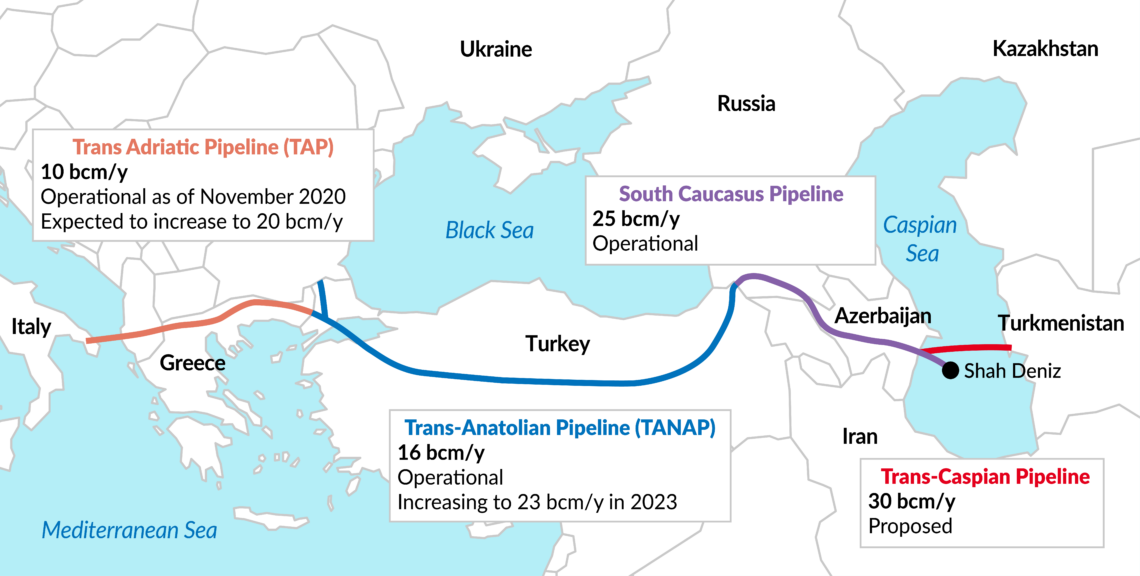

The centerpiece of this concept is the proposed Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP). This long-debated project would pump gas from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan and onward into the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) that runs via Turkey into southeastern Europe.

Facts & figures

There are several reasons why the TCP is likely to remain little more than a vision. With all recent Turkmen field development under contract to China, there is no clear source of gas for the TCP. Under current market conditions, it is hard to see it become commercially viable. Also, there is no guarantee that the operators of the SGC will commit to the necessary capacity expansion. This said, the renewed interest in the TCP shows how regional geopolitics are changing in favor of Azerbaijan and Turkey. In the end, the geopolitical benefit may trump commercial caution. Western powers have long supported the TCP, which would bypass Russia.

New routes

Turkey is also working on extending other major transport infrastructure projects across the Caspian Sea. One would open a route to Kazakhstan and onward to the dry port of Khorgas on the Chinese border. The other would breathe new life into the Lapis Lazuli Corridor that crosses Turkmenistan and ends in Afghanistan. Again, both represent a direct challenge to Russia, whose traditional role in the region has been associated with transport infrastructure running from north to south.

The route through Kazakhstan forms part of the larger “Trans-Caspian International Transport Route” (TITR) that originates in China and terminates in Europe. In 2013, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Kazakhstan established a committee to coordinate the TITR’s “Middle Corridor” through the Caspian Basin. The link combines rail transport with shipping across the Caspian, from Aktau in Kazakhstan to Baku in Azerbaijan. From there, the route proceeds to Georgia where it splits into spurs to Turkey and across the Black Sea to Europe.

Facts & figures

Ankara joined the project in 2018, motivated by the completion in October 2017 of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars Railway. The current plan is that the Nakhchivan corridor will provide a further boost, increasing Turkey’s role in the rollout of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Russia, which also hopes to profit from the BRI, opposes the plan.

The Lapis Lazuli Corridor forms another important part of this strategy. Following an opening ceremony in December 2018, in January this year representatives of Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Afghanistan met to agree on a road map for deeper cooperation. The link westward from Turkmenistan proceeds via ferry from Turkmenbashi to Baku and then by rail to Georgia, Turkey and Europe.

The main rival here is Iran. In 2014, it launched a pivot toward Central Asia that included a free trade deal with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. Seeking to undermine competition from Turkey, in October 2014 Tehran more than doubled its transit tariffs and in January 2015 it announced it would stop providing fuel for Turkish trucks.

Bypassing Iran

It was in response to these moves that Turkey began to look in earnest for ways to redirect its trade flow across the Caspian, bypassing Iran. Its incentive to do so increased as the flow of Turkish trade through Iran rose, from 565,000 tons in 2016 to 1.08 million tons in 2019.

The opening of the Nakhchivan corridor promises to deal a double blow to Iran. Tehran not only risks losing much of the transit traffic that circumvented Armenia as it flowed between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave, but also the lucrative flow of goods from Turkey to Central Asia. At a planning session in 2015, Turkmenistan’s ambassador to Turkey, Ata Serdarov, envisioned that the Trans-Caspian route could handle all Turkish trade to Central Asia without crossing Iran.

Kazakhstan wants a greater regional role for Turkey, to balance Russia and China.

One factor that speaks in favor of Ankara’s soft power is that Kazakhstan wants a greater regional role for Turkey, to balance Russia and China. Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine has upset Kazakh elites, while Beijing’s maltreatment of its Muslim Uighur minority in neighboring Xinjiang has angered much of the Kazakh population.

It is also important that major investments have gone into developing infrastructure on an east-west orientation. In 2018 Turkmenistan opened its new Turkmenbashi Sea Port, while Azerbaijan inaugurated the Baku International Sea Trade Port. The latter is located at Alat, some 70 kilometers south of Baku, where the country’s main railway and highway networks converge. Recently, officials in Kazakhstan have also announced plans to greatly increase capacity at the Port of Aktau, allowing more goods to flow from Azerbaijan to Turkey.

Rivals’ response

Russia and Iran have responded to these developments with saber-rattling. The two have considerably larger naval assets in the Caspian than the other three littoral states, and they have repeatedly staged joint naval drills to highlight this advantage. It was no coincidence that one such drill was conducted while the armistice in the Nagorno-Karabakh war was being negotiated.

By taking a decisive stance in the South Caucasus, Turkey has enhanced its position in Central Asia.

It is true that much of the speculation about an increased role for Turkey in Central Asia rests on the Nakhchivan corridor, which remains in the hands of Russia. This said, even if it should fail to live up to expectations, it has already played an important role in transforming regional geopolitical expectations.

By taking a decisive stance in the geopolitics of the South Caucasus, Turkey has enhanced its position in Central Asia. As it deepens its cooperation with the states in the region, it will play an increasingly important role in balancing the influence of Russia and China.

In the words of a seasoned observer, perhaps the most important fallout of Azerbaijan’s victory in the Nagorno-Karabakh war “is to be found in the new way that the countries of Central Asia increasingly view it as a bridge to the West – something that will only increase the influence of Azerbaijan (and behind it, Turkey) in the Turkic republics of that region.”