The security risks of 5G

The 5th generation of cellular wireless technology, or 5G, will connect the world like never before and present serious security vulnerabilities. At the same time, the Chinese presence in telecommunications sectors across the globe is growing. The U.S. is concerned China could gain access to sensitive data.

In a nutshell

- Chinese firms are gaining ground in telecoms sectors around the world

- The introduction of 5G will create new security vulnerabilities

- The U.S. worries that China will use its firms to exploit these vulnerabilities

Widespread deployment of 5G technology is still years away, but there is growing public attention being paid to the immense benefits of enhanced wireless connectivity. With maximum speeds that are more than 100 times faster than currently available, the next generation of cellular technology will reshape economies and cultures. It is also increasingly apparent that the new wireless networks will heighten national security risk and the potential for geopolitical conflict.

If predictions prove accurate, 5G will bring an unparalleled level of connectivity to every aspect of daily life. Semiconductor and telecommunications equipment maker Qualcomm characterizes it as a “unifying connectivity fabric for our society.”

Greater reliance on 5G networks also equates to greater cyber insecurity. This heightened vulnerability will coincide with the peaking of China’s command of wireless technology, both as a manufacturer of electronics and as an aggressive (and subsidized) financier of 5G deployment across Eurasia. All of this prompts deep concern about 5G security among the United States and its allies.

Understanding 5G

The term “5G” refers to the fifth generation of cellular wireless technology. As with the existing network, 5G will transmit data through radio waves to cell sites arrayed across the landscape. The cells connect to the larger network through a wired “backbone.” Unlike earlier wireless technology, 5G can transmit across a broader range of frequencies. Coupled with advances in antenna technology, the new generation will move data exponentially faster and in greater volume. It also dramatically reduces “latency” (the time it takes for a data message to reach its target and initiate a response).

The ‘Internet of Things’ could incorporate more than 75 billion devices worldwide by 2025.

In a recent 5G test shared on Twitter, telecommunications firm Verizon demonstrated a remarkably fast download speed of 762 megabits per second (Mbps) on a handheld cellular phone. Test conditions were optimal, of course, with a cell tower in close range and minimum network traffic, but the results were impressive nonetheless. Currently, the average mobile download speed is 27 Mbps.

The capabilities of 5G are expected to expand dramatically the variety of wireless products and services as well as the number and type of devices equipped for wireless control via the internet. Data aggregator Statista estimates that the “Internet of Things” will incorporate more than 75 billion devices worldwide by 2025 – a fivefold increase in 10 years.

The international 5G standard was finalized in June 2015 by the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (GPP), a coalition of seven groups that governs technical specifications for mobile broadband. The 5G technology was developed by Qualcomm, Huawei, Ericsson, Samsung and Nokia.

Internet service providers are currently testing 5G in a handful of cities, and as yet there is no mass production of new mobile devices. Given the nature of 5G – the need to manufacture and place a multitude of small cells in close range – actual deployment of new networks will require enormous amounts of financial and human capital.

The security calculation

All wireless networks face security challenges such as unauthorized access (hacking) and unauthorized data interception. The extent of the threats is a function of the scope of connectivity. That is, the risk reflects our network reliance. Security protocols are evolving with technology, of course, but so is misconduct; the cycle is unending.

Can Chinese firms be trusted to not tap the data flows across wireless broadband around the world?

The global prominence of China’s technology sector poses a dilemma for many countries as they contemplate deployment of 5G networks. Can Chinese firms be trusted to not tap the data flows across wireless broadband around the world? What degree of security can be sacrificed in exchange for Beijing’s largesse? What are the risks of China’s access to consumers and businesses throughout Europe and Asia?

The administration of U.S. President Donald Trump is attempting to convince allies that the security calculation calls for a ban on 5G technology from China. As President Trump said in mid-April, “5G networks must be secured. They must be strong. They have to be guarded from the enemy.”

The “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance (composed of the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) are divided about whether to bar domestic use of 5G components from Huawei, China’s leading electronics manufacturer.

A report released earlier this month by the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence concluded that Huawei technology is indeed conjoined with Beijing’s intelligence operations:

The growth of Chinese technology companies has made them a global market power. This is largely a product of focused government industrial policy and funding instruments. Chinese companies are not only subsidized by the Chinese government but also legally compelled to work with its intelligence services. Whether the risk of such collaboration is real or perceived, the fear remains that adopting 5G technology from Huawei would introduce a reliance on equipment which can be controlled by the Chinese intelligence services and the military in both peacetime and crisis.

Huawei was founded in 1987 by Ren Zhengfei, a former officer of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. It is now a global provider of technology for information and communications networks, smart devices, and cloud services – with annual sales exceeding $86 billion. The Huawei website states: “We are committed to bringing digital to every person, home and organization for a fully connected, intelligent world.”

That is precisely what most worries the U.S. and other democracies. China’s National Intelligence Law compels citizens, companies and organizations in the country to “cooperate” in government intelligence operations. That effectively makes Huawei’s IT and telecom networks extensions of the Chinese government.

The company’s wireless equipment is ubiquitous throughout the European Union, which is China’s top trade partner. Critics contend that subsidies from the government of China allow Huawei to undercut competitors’ prices. And through its Belt and Road Initiative, China has also invested billions of dollars in infrastructure projects across Central and Eastern Europe.

Facts & figures

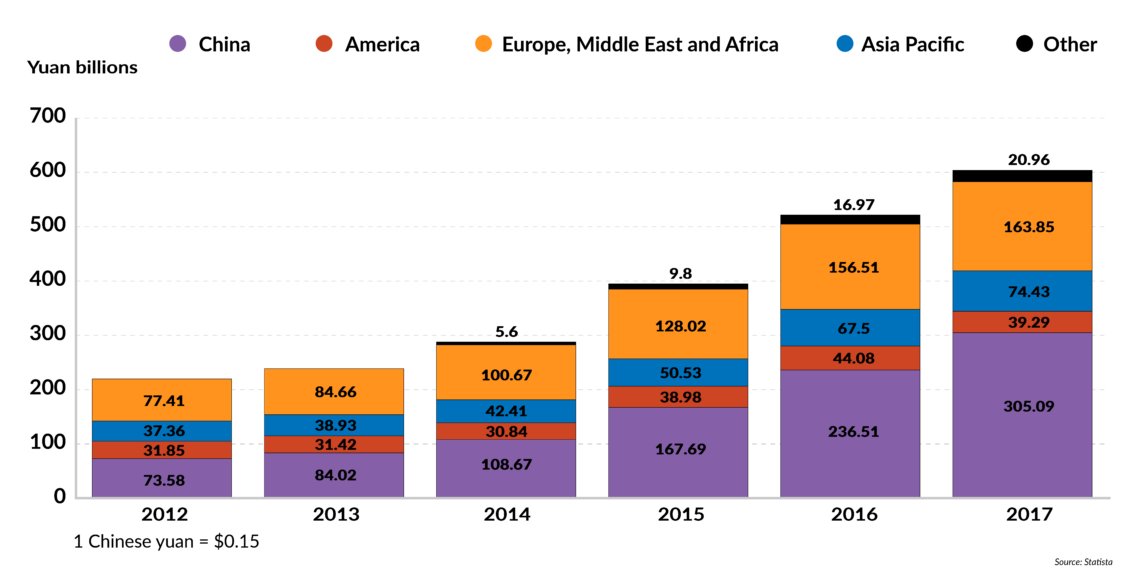

Huawei high

Huawei's revenue by geographical region

(2012-2017, billions of yuan)

Company officials deny that subsidies have gained them market share and point out that Huawei has a cumulative credit line of $33 billion from foreign banks. The subsidy allegations, they say, are a front for trade protectionism.

“It’s not true that Huawei uses subsidies to gain market share,” Chen Lifang, Huawei’s global board director, told Reuters. “We receive legal subsidies. Like European countries, China also gives out subsidies for R&D-related activities. Huawei has taken part in such European and Chinese schemes.”

Huawei fights back

Huawei holds less than a 5 percent market share in the U.S. – mostly in small rural networks. But the Trump administration is urging allies to boycott the company’s equipment in deploying 5G networks. Said U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo: “If a country adopts [Chinese technology] and puts it in some of their critical information systems, we won’t be able to share information with them, we won’t be able to work alongside them.”

The most recent National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the military funding measure, bars the government purchase of products from Huawei and its Chinese rival, ZTE Corp.

But Huawei is challenging the prohibition as unconstitutional in a lawsuit filed on March 6. Company officials contend that the law violates due process rights and the separation of powers doctrine.

According to Guo Ping, a Huawei chairman, “In enacting the NDAA, Congress acted unconstitutionally as judge, jury and executioner. Regrettably, the NDAA was enacted to restrict Huawei without giving us the opportunity to defend ourselves.”

Huawei is pushing back in the U.S. courts to show the world they’re trying to fight limits on its 5G business.

The likelihood that the suit will succeed is “slim to none,” said Dileep Srihari, the senior policy counsel and director of government affairs for the Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA), who participated in a Federalist Society forum on Huawei and 5G security. “That’s not the only reason they would have filed a lawsuit because it certainly could be seen, and many people have said this, that it’s part of a global public relations strategy by Huawei to not just accept the U.S. government’s decisions and conclusions as a sort of fait accompli but to try and push back legally to show the governments of other countries around the world that they’re trying to fight this in the U.S. courts.”

Meanwhile, the company has hired a high-profile lobbyist, Samir Jain of the law firm Jones Day, to represent the company on issues related to foreign investment, government purchasing and security arising under the National Defense Authorization Act, according to a disclosure filing. Mr. Jain served in the Obama Administration as the senior director for cybersecurity policy with the National Security Council, as well as a former associate deputy attorney general.

Although cognizant of the security issues, the European Commission has not signed on to the Trump Administration’s proposed ban. Instead, the commission in March directed member countries to undertake a cyber risk assessment and develop 5G safeguards by year’s end. Such measures could include testing and certification requirements for products deemed as potential security risks, according to Reuters.

“We need to develop a European approach to protecting the integrity of 5G,” said Julian King, the EU commissioner for the Security Union.

But Mr. Srihari of the Telecom Industry Association said such measures are insufficient. “[T]he notion that somehow it is possible to design a standard or a test, or any suite of standards or tests, and thereby say that this product has not been compromised by Chinese intelligence is just really not realistic.” The threat, he added, “is really hard to defend against because it can be hidden very deeply in the source code of a product in a way that, even with millions and millions of dollars of forensic computer scientists reading every line of the code, would be incredibly difficult to pick up. And that leaves aside even the possibility that you could have hardware-level exploits inserted in the chips of a product at very low levels of design that would be practically uncatchable unless you had, again, access to all of the chip designs. And even then, it could be very cleverly hidden.”

The lure of lower-cost deployment and other investment appears to be trumping security concerns among some European countries. Following a Huawei meeting in Beijing on April 9, for example, Hungarian Finance Minister Mihaly Varga said Huawei would help his country meet its goal of high-speed internet access for 90 percent of families by 2025.

Meanwhile, opinions about Huawei are split in the Czech Republic, according to the Associated Press, which reported that the country’s National Cyber and Information Security Agency is following the warnings of U.S. authorities despite criticism from President Milos Zeman. Huawei has pledged to invest $370 million in 5G networks in the Czech Republic.

Scenarios

China’s dominance in 5G technology is prompting calls for government subsidies to American firms. But there is no way for the U.S. to out-China China – especially when only one of the top five manufacturers of 5G technology is American.

U.S. allies also seem unconvinced at present that a ban on Huawei 5G products is justified. That attitude could change if Chinese espionage on the network is uncovered – but countries are not likely to disassemble their 5G networks and start over.

The best the U.S. can hope for is to counter the security threat with superior security and/or an alternative to the current 5G cell technology. Therein lies its comparative strength and its best hope for a more secure future.