Political and economic freedom in Africa

Development performance throughout the African continent reflects global trends. Free regimes in Africa tend to go hand in hand with economic freedom, resulting in growth and increased human development. With sound economic reforms, this virtuous circle could intensify.

In a nutshell

- Democracy is positively correlated with a market economy

- Planned economies often coexist with predatory politics

- Political and economic freedom could increase steadily

Economic and developmental performance is an important way to legitimize (or delegitimize) a regime. In Africa, events in Zimbabwe, South Africa, Sudan or Algeria suggest that economic marginalization and material deprivation have a destabilizing effect on societies and politics, while the improvement of living standards strengthens political regimes, regardless of their authoritarian or democratic credentials.

Africa combines different political and economic arrangements, ranging from dictatorship in Equatorial Guinea to full-fledged democracy in Cape Verde, from a market-oriented economy in Mauritius to a command economy in Eritrea. Evidence in Africa suggests, to a certain extent, a positive correlation between political and economic freedom – a trend that can also be observed globally. Like North Korea or Turkmenistan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea or the Central African Republic are among the least free and least prosperous countries in the world. However, this relationship is not straightforward; for example, in Rwanda a market economy coexists with political authoritarianism.

Market-economy policies go hand in hand with political rights and civil freedoms.

Interestingly, while socialism is regaining credibility in the West, in Africa many countries – including Angola, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Ghana and Zambia – are progressively opening their economies.

Governance

While inherited features – chiefly geography and the colonial legacy – help shape economic and developmental outcomes, current political conditions play a crucial role. Here the key variables are stability, leadership quality and institutional strength. Insular or landlocked countries with scarce resources like Cape Verde or Rwanda, for example, have delivered better results than resource-rich countries with initial competitive advantages like Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Good governance and sound macroeconomic policies are also necessary to convert growth into development. During the 2000s commodity boom, Angola, Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea attained impressive growth rates, but their transformational effects fell short of expectations.

Facts & figures

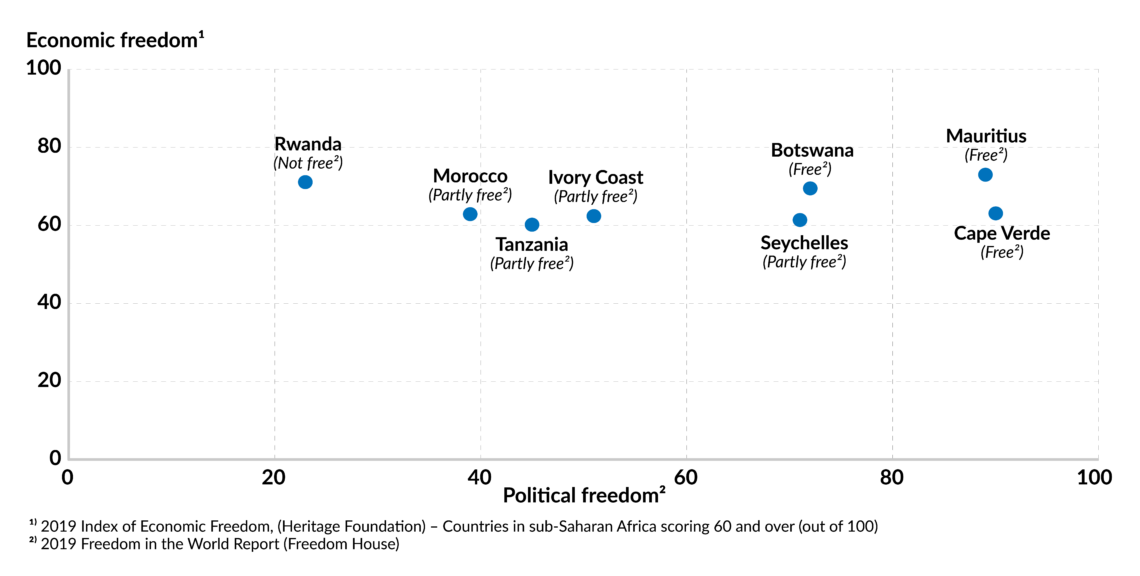

Best African Performers (Economic Freedom)

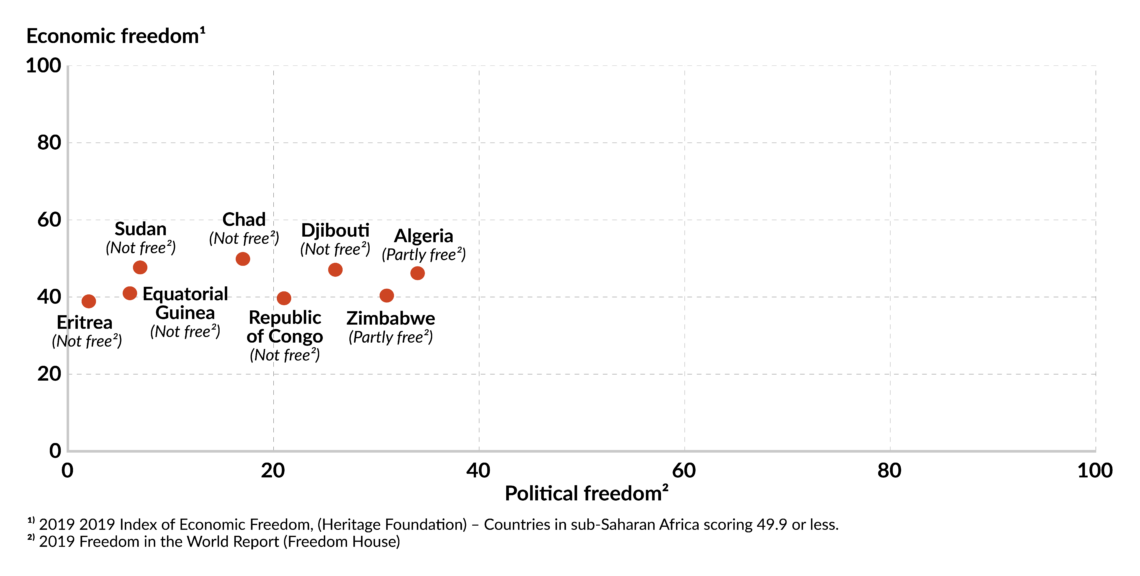

In Africa, with a few exceptions, there is a clear correlation between democracy and market-oriented policies. Among the eight African countries with the lowest rankings in the 2019 Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom, seven are classified politically as “not free” by the 2019 Freedom in the World report compiled by Freedom House. The only country classified as “partly free” is Zimbabwe, a recent upgrade following the end of Robert Mugabe’s rule. On the other hand, among the eight African countries with the highest economic freedom scores, only Rwanda is classified as “not free” by Freedom House.

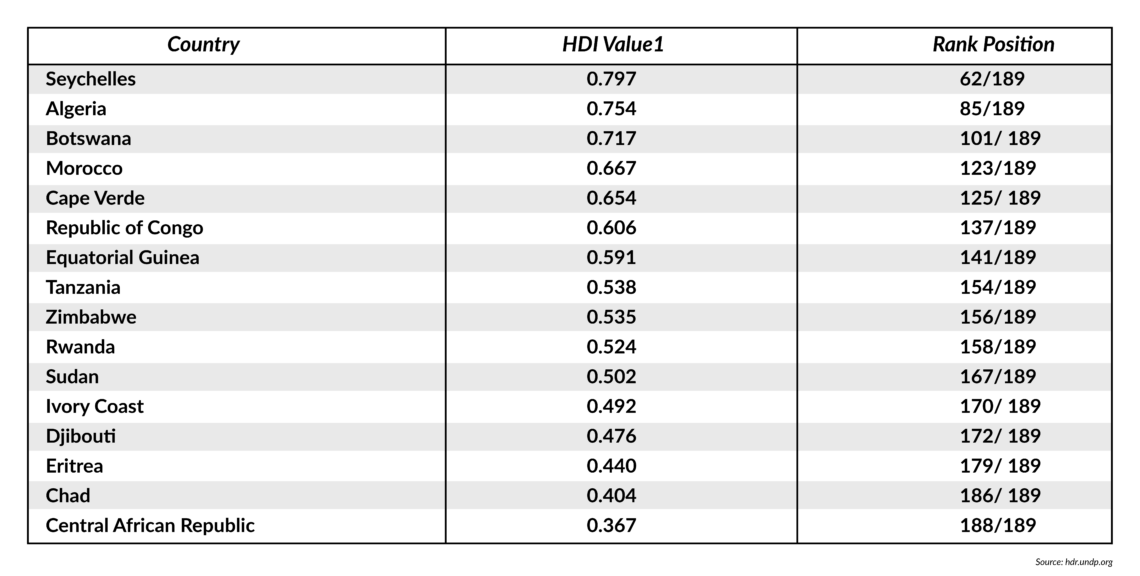

Another trend is identifiable by looking at the countries’ developmental status as rated by the Human Development Index (HDI). Four out of the eight freest economies are also among the most developed countries, while four out of the eight least free economies are among the worst developmental performers.

Diversity

Some African countries pursue diametrically opposite developmental models. In countries like Mauritius, Botswana and Cape Verde, market-economy policies go hand in hand with political rights and civil freedoms. In authoritarian regimes with relatively closed economies, however, centralization and predatory politics tend to go together under the harsh logic of political survival. The latter description applies to Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe and Sudan under the rule of Omar al-Bashir, and it remains valid in places like Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea or the Republic of Congo.

Facts & figures

Worst African Performers (Economic Freedom)

Apart from these extremes, however, other arrangements are common. In Algeria and Nigeria, economic dirigisme – based on state mechanisms like subsidies of basic goods and price controls – is part of the social contract. While these are not closed or fully centralized economies, they are characterized by state intervention in key sectors (through policies of nationalization), excessive red tape, relatively weak property rights and large state bureaucracies. Meanwhile, Rwanda and, to a certain extent, Ethiopia represent a different model of market-oriented authoritarianism. In both cases, the ruling party assumed a command role in the economy at the early stages of capitalism, while pursuing firm strategies of state-led development. Though Rwanda still lags behind Zimbabwe in terms of HDI, if we adopt a comparative and relative approach, its economic and developmental performance since 1994 has been impressive. Between 1996 and 2017, Rwandans’ life expectancy almost doubled from just under 36 to more than 67 years, while the country’s HDI score increased from 0.332 to 0.524.

Finally, there are “intermediate” countries that are undergoing a transformation process. The Ivory Coast, which has been among Africa’s fastest-growing economies over the past eight years, is a top reformer, having moved up 55 positions in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index between 2013 and 2018. In Ghana, once an exponent of African socialism, President Nana Akufo-Addo has implemented a series of major reforms, including the liberalization of the cocoa market, sales of state-owned enterprises, the progressive elimination of subsidies and the promotion of investment and entrepreneurship. Like President Paul Kagame in Rwanda, Mr. Akufo-Addo is also prioritizing self-reliance, through the “Ghana beyond aid” initiative. Since President Joao Lourenco came to power, Angola – sub-Saharan Africa’s third-largest economy – has also abandoned the socialist rhetoric which characterized the previous era, while concrete efforts are being made to reverse predatory politics.

Opportunities and challenges

After gaining independence in the 1960s and early 1970s, many African countries turned to socialism. In a polarized global context, capitalism was perceived as an extension of colonialism and socialism as a necessary antidote to any form of exploitation. Marxist influences, often mixed with nationalist and pan-Africanist trends, gave rise to different formulas, from Kwame Nkrumah and Julius Nyerere’s African socialism (ujamaa) to Mozambique’s disastrous agrarian reform, Mengistu Haile Mariam’s years of dictatorship and famine in Ethiopia, and military regimes in Burkina Faso, Congo or Somalia. These failures and their ongoing effects also explain why, albeit with important exceptions, African leaders are abandoning socialist solutions.

Facts & figures

Human Development Index Value of African Countries in 2018

Unlike Europe, the main threats to economic freedom in Africa have less to do with high tax burdens, government overspending or excessive regulation than with political institutions and the rule of law. Three other factors can seriously undermine prospects for economic freedom and prosperity: 1) a high poverty rate combined with fast demographic growth, which calls for a difficult balance between state intervention and growth-enhancing policies; 2) heavy aid dependency, which can occur even among top economic performers like Rwanda; 3) the coexistence of formal, informal and traditional economies, whose complicated interplay presents a challenge for policymakers in most African countries.

Despite these difficulties, there are reasons for optimism. African countries have significant growth potential, with many ranked each year among the world’s fastest growing economies. Assuming that sound policies are implemented, the growth elasticity of poverty is high, meaning that economic growth can significantly and rapidly reduce deprivation. In India, for example, multidimensional poverty incidence has almost halved in ten years (2006-2016), dropping to 27.5 percent from 54.7 percent, as 271 million people exited poverty. Serious poverty reduction in India occurred after liberal reforms were introduced in the early 1990s, in response to widespread deprivation, accelerating population growth and fast urbanization.

Several African countries have two other important assets. The first is what Ghanaian economist George Ayittey defines as “the cheetah generation”: a new cohort of future-oriented, dynamic and pragmatic young Africans who demand more accountable and efficient leaders. Their potential is reflected in technical innovations like M-Pesa, the Kenyan mobile money app; iCow, an SMS information service designed to optimize production among small livestock farmers; SafeMotos, a tech enterprise based in Kigali that adapted the Uber concept to African reality; and Flutterwave, a Nigerian fintech start-up focused on simplifying payment processes across Africa. The second asset – which follows from this growing capacity for innovation – is Africa’s opportunity to leapfrog developmental challenges. These favorable circumstances could help open up more economic opportunities and improve living standards throughout the continent.

Scenarios

Politically, recent years have been marked by the fall of longtime rulers in important countries like Angola, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Algeria and Sudan. These upheavals have brought different, and in some cases still unknown, outcomes – from an acceleration of reform impetus in Angola and Ethiopia to the potential for even greater conflict in Sudan. In economic terms, the continent seems to be moving toward market-oriented policies, more orthodox monetary policies and trade liberalization – although there are significant exceptions. Given this current context, two main scenarios must be considered.

Economic freedom leads to political freedom

Under this first and more likely scenario, the expansion of political and economic freedom would slowly but steadily continue throughout Africa, as regimes’ economic and developmental performance becomes more relevant in political terms. Entrenched leaders of authoritarian regimes in countries where much of the population is poor – Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo and Eritrea come to mind – would eventually be ousted. While the pace and outcome of these political changes are uncertain, they would mark a clear shift in how power is legitimized in Africa, serving as a warning to political leaders throughout the continent. They would also expose the limits of an implied social contract based on a trade-off between providing subsidized basic goods and tolerating corrupt ruling elites.

This scenario depends mainly on three factors. First, economic reforms need to be successfully implemented in “intermediate” countries like Ivory Coast and Ghana (both among Africa’s fastest-growing economies in 2019, according to the IMF) and political outcomes need to become clearer in regimes of market-oriented authoritarianism. Among the latter, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed seems determined to accelerate economic and political freedoms, while Rwanda continues to score successes in growth and development (Ethiopia and Rwanda are also among the fastest-growing African economies in 2019). Second, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which recently entered into force, must prove effective if countries are to become more self-reliant and less aid-dependent. Finally, weak growth and a reluctance to embrace market-friendly policies in South Africa and Nigeria have set the continent’s two biggest economies at odds with the trend toward greater economic freedom and prosperity.

Business as usual

This second scenario, in which forces supporting the status quo successfully resist advocates of change, is slightly less likely to occur. This outcome could nevertheless result from a combination of economic and political factors. Economically, structural reforms throughout the continent could be compromised by a global economic slowdown, as trade tensions, volatile commodity prices and interest-rate uncertainty take their toll on emerging market economies. Africa’s biggest economies would continue to underperform, while ill-considered land reform in South Africa would weigh on the whole Southern African Development Community (SADC), darkening the economic outlook in Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

In political terms, possible triggers for this scenario include failed transitions in Africa’s market-oriented and semi-authoritarian regimes (Ethiopia and Rwanda), ongoing tensions in Sudan, and the continued survival of the continent’s remaining longtime dictators.

Each of these trends would help perpetuate a vicious cycle of dependency, as they would encourage most economies to remain heavily aid-dependent. By fostering the persistence of dirigisme and authoritarianism, they might leave most African citizens with very modest levels of political and economic freedom.