The potential of Prosper Africa

Washington’s most recent strategy for Africa revolves around the Prosper Africa initiative, whose aim is to double trade and investment between the U.S. and the African continent. If implemented correctly, the private-sector-focused and aid-independent action plan could result in a win-win situation for both.

In a nutshell

- The Prosper Africa initiative is based on sound principles, but lack of funds could threaten its success

- The U.S. needs to increase trade with Africa to stay ahead of China and other players

- Africa could gain a bigger share of the U.S. market if governments prove responsive enough

In December 2018, after more than two years of apparent disinterest, the United States unveiled its strategy for Africa. True to the spirit of the current administration, it is a pragmatic engagement plan, focused on advancing American interests through strategic cooperation with African countries, mainly on the security and economic fronts. While unambitious and lacking democratic goals, this strategy – if adequately implemented – may not only advance American and African interests, but also help strengthen American leverage on the continent.

Strengths and weaknesses

The centerpiece of American economic strategy for the continent is the Prosper Africa Initiative, which aims to double trade and investment between the U.S. and African countries, opening African markets to American businesses and vice versa. In practice, the initiative will minimize investment risks for American companies willing to operate in Africa through the creation of a more favorable environment (including the creation of a one-stop shop for investment services, facilitating export credit insurance and working capital loan guarantees, as well as attempts to negotiate bilateral free trade agreements). The initiative is expected to increase economic growth.

In a moment marked by the worldwide influence of hybrid models of “authoritarian” or “state-led” capitalism, Prosper Africa represents an alternative development and political paradigm.

There are two main limitations to the successful implementation of this initiative. The first is a lack of adequate resources. Prosper Africa is mainly a coordinating mechanism whose success greatly depends on efficiency gains. The $50 million allocated to its implementation by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) may fall short of what is needed.

In a moment marked by ‘authoritarian’ or ‘state-led’ capitalism, Prosper Africa represents an alternative.

A second, more crucial, obstacle has to do with diplomacy. Africa has been largely neglected in both the discourse and the practice of this administration. As the end of his first term draws nearer, President Donald Trump has yet to visit the continent. Important diplomatic posts – including in Tanzania and Chad – have remained indefinitely vacant after the president ordered politically appointed ambassadors to step down. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump’s decision to appoint a handbag designer with no diplomatic background to serve as ambassador to South Africa was met with confusion in Pretoria. Last but not least, Washington did not send a U.S. cabinet member to participate in the launch of Prosper Africa at the U.S.-Africa business summit in Maputo, Mozambique.

While converging economic and security interests may prevail over these incidents and omissions, soft power remains an important element for engagement with the African continent.

Considering these limitations, the strength of Prosper Africa lies mainly in its new, more promising, legal and institutional framework, which will likely facilitate American investments on the continent. In 2018, the bipartisan Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act established the creation of the United States International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), a new development agency with a $60 billion budget. Its focus is private capital development finance, which will integrate the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and the USAID’s Development Credit Authority.

Sub-Saharan Africa already accounts for 27 percent of the OPIC portfolio. In 2018, OPIC launched the Connect Africa Initiative, which aims to invest more than $1 billion in infrastructure, communications and value-chain connectivity across the continent. OPIC is currently better equipped to compete on the global stage since it can now invest up to 20 percent of the total equity of the project.

Trade relations

Despite the persistence of political and economic risks, an increasing number of African countries have been consolidating their position as attractive markets and investment destinations thanks to high growth margins and high return rates. Defying the global trend, foreign direct investment into Africa increased by 11 percent in 2018.

However, U.S. engagement with the continent remains mainly focused on foreign assistance. Washington is the leading provider of official development assistance (ODA) to Africa, accounting for 21 percent of the net disbursements in 2017. Throughout the last decade, the U.S. provided on average $9 billion a year in foreign aid to Africa, and while this is more than China, the latter’s investment on the continent has doubled between 2010 and 2016. In 2018, President Xi Jinping committed an additional $60 billion to the continent for the Belt and Road Initiative through development finance, concessional loans and investments.

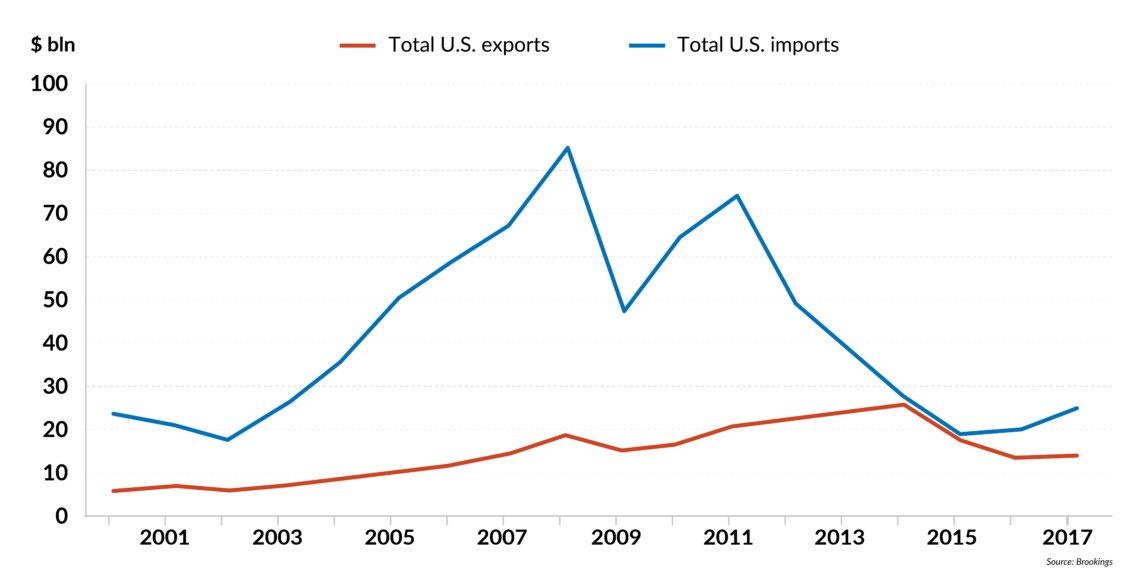

Although trade is not a zero-sum game, the competitiveness of U.S. products is being challenged by old and emerging powers. Trade relations between the U.S. and African countries are largely determined by the 2000 African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a nonreciprocal program which – under pre-established eligibility criteria – grants trade preferences to African countries. The AGOA Act was extended in 2015 and will expire in 2025. While AGOA has contributed to a significant increase in two-way trade (which peaked at $100 billion in 2008) and had a positive impact on most beneficiary countries through stimulus, economic diversification and job creation, its preferential rather than reciprocal approach is becoming outdated in light of the current global economy.

Facts & figures

U.S. trade with sub-Saharan Africa, 2000-2017

In 2009, China beat the U.S. and became Africa’s first trading partner. Two-way trade between Africa and the U.S. has declined by 32 percent since 2014. And while the value of China-Africa trade has been decreasing since 2014 (reflecting the deceleration of the Chinese economy), the total value of trade in 2017 was estimated at $148 billion, far above the U.S.-Africa figure of $39 billion. American trade with Africa is also excessively concentrated in specific countries and sectors: oil still accounts for most U.S. imports, and South Africa and Nigeria remain the top trade partners and investment destinations.

The European Union, an enthusiastic supporter of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), has been consolidating its position as Africa’s first trading partner, mainly through the Economic Partnership Agreements (Brussels has signed EPAs with 41 African countries). The EU is also in a privileged position – compared to the U.S. – to negotiate free trade agreements with the AfCFTA, if signatory countries will agree to the creation of a customs union.

It is also worth noting that India has increased its imports and exports to Africa by 181 percent and 186 percent respectively in 2017, becoming Africa’s fourth-largest trading partner (after the EU, the U.S. and China).

Determinants of the strategy

To fully understand the Prosper Africa Initiative it is necessary to consider the broader context of U.S.-Africa relations. Washington’s strategy for engaging with Africa is based on the “America first” principle, favoring bilateralism to the detriment of multilateral or global approaches and abandoning the ideological crusades that characterized the foreign policy strategies of former President George W. Bush and, to a lesser extent, Barack Obama. Prosper Africa is firmly based on the idea that enterprises – rather than aid – are the leading force of development (foreign aid now accounts for only 1 percent of the U.S. budget), and puts more emphasis on the sovereignty and economic efficiency of host nations than on their democratic credentials.

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. has maintained a strong presence in Africa’s security landscape.

Prosper Africa is also aligned with Washington’s security concerns. Under the Trump administration, the U.S. has maintained a strong presence in Africa’s security landscape, namely in the so-called “arc of instability,” ranging from Mauritania to Somalia. A more prosperous Africa would prove less fertile ground for extremist militancy.

Finally, the U.S. strategy also constitutes a hard- and soft-power response to the growing influence of China, Russia, India and the EU in Africa. By placing free, transparent markets and private initiative as the main drivers of prosperity, Washington is offering an alternative to the models of authoritarian or “state-led” capitalism.

Scenarios

The success of the Prosper Africa Initiative will depend on a combination of factors, including the evolution of internal U.S. politics, the responsiveness of African countries' governments and the development of global trends.

Considering this, the most likely scenario is relative success. The next years will see continuity, to the extent that U.S. engagement in Africa will remain based on the principles that shaped the Prosper Africa Initiative. While Africa is expected to remain – at least rhetorically – a low priority on the Trump administration’s agenda, the renewed institutional and legal framework will contribute to increasing trade volume and investment flows, providing a soft landing for the expected decrease in aid assistance. Considering that aid flows are expected to decrease also at the global level, the fact that the U.S. strategy is private-sector-focused and aid-independent will represent a competitive advantage in comparison to other players like Europe.

Increases in two-way trade and investment will result in a win-win situation. African companies and products will have access to a bigger share of the American market and benefit from the American know-how in capital innovation and capacity building, while increased access to African low-value goods could strengthen a dynamics of specialization, with American companies focusing on sectors in which they have a competitive advantage, namely services and high-value goods. Prosper Africa, under this scenario, could pave the way to a more reciprocal alternative to the AGOA framework.

But while relations are expected to increase, in the medium term, the goal of increasing trade will likely be compromised by lack of resources, low diplomatic engagement and excessive focus on bilateral arrangements. This approach could prevent companies from entering the African market, especially considering the enthusiasm, among African countries, for the regional model of the AfCFTA.

Under the second, less likely scenario, the implementation and evaluation of Prosper Africa would be defined by U.S.-China competition rather than convergence between the interests of the American and African private sectors. Under this “Cold War” zero-sum game perspective, American diplomats and development agencies would adopt an “us vs. them” logic which would negatively affect both economic and political relations since, at least in the medium term, the U.S. cannot compete with Beijing’s advantages on the continent.