Africa’s window of opportunity on trade

Liberalizing trade across the continent would help African nations shape emerging ties with global powers like the U.S. and China.

In a nutshell

- World powers are courting African countries as trading partners

- A continental free trade agreement has yet to be fully realized

- Bilateral approaches to trade will make regional integration difficult

As the post-pandemic economy takes shape, Africa is set to play a significant role in influencing world trade and investment flows. The continent is home to massive infrastructure investment, with projects largely financed and built by China.

Changes to the global order caused by the war in Ukraine have also put Africa in the geopolitical spotlight as a new arena for the struggle between China and the United States. As U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken put it during an August tour of South Africa, Congo and Rwanda, Washington sees Africa as an “equal partner” that will not be “dictated to.”

Mr. Blinken’s visit had to contend with China’s growing presence in the region, which has seen Beijing fund a number of large projects, including in Kenya and Mozambique. The unwillingness of many African countries to condemn Moscow for its invasion of Ukraine has also raised concern among the U.S. and allies over whether they will serve as a trade “buffer zone” to help Russia mitigate Western sanctions.

One way or another, Africa is a growing part of the global trade map. After Covid-19, its economies will increasingly attract investment, delivering returns to investors despite the region’s political challenges. The question is whether African countries will be able to negotiate strong terms amid a shifting geopolitical order.

Bilateral deals

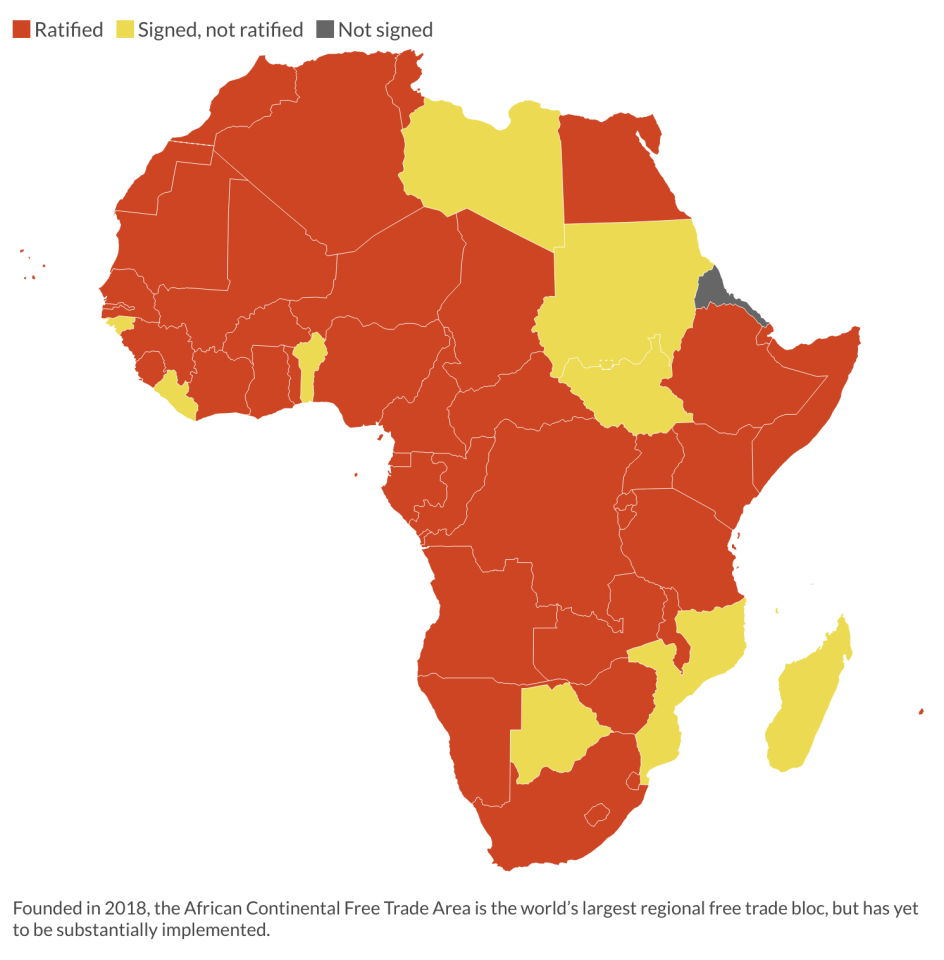

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which was signed in 2018 and launched in 2021, establishes the world’s largest regional free trade bloc. But beyond assenting to it, most African countries have not shown a commitment to make free trade a full reality.

At the 42nd Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) summit, held in Kinshasa in August, delegates focused on Africa’s geopolitical positioning regarding ongoing tensions between the U.S. and Russia. They insisted that Africa should not simply be directed by world powers to adopt a particular stance on issues such as the war in Ukraine. African leaders have emphasized that taking a side on the conflict would not necessarily benefit their countries, whose more immediate priorities include addressing poverty and inequality at home.

Most African countries have not shown a commitment to make free trade a reality.

African states may be able to deflect Western pressure over geopolitical matters, but that itself will not translate into better trade deals. Extending free trade in Africa would be a far more powerful tool in shaping relations, economic and otherwise, with global partners.

The bilateral approach to economic ties that currently dominates between various African countries and world powers has not furthered regional trade solidarity. African states tend to enter these bilateral trade agreements from a position of weakness, with terms dictated by more powerful partners.

Common market

By enhancing free trade and developing a common regime across the region – coupled with more stability in terms of laws and institutions – Africa can negotiate better terms of engagement with major trading partners such as the U.S. or China. Instead of being driven by national interests, such an agenda would be grounded on inclusive and sustainable growth, and advance democratic principles.

The current strategy on trade taken by various countries with world powers has led to an inconsistent trade regime on the continent, making economic integration more difficult. A common African market based on shared principles could surpass the differences imposed by historical circumstances across jurisdictions.

Facts & figures

While the SADC summit heralded a commitment to opening local markets and unlocking value in agriculture and agro-processing, it also saw criticism from South Africa over decisions by Botswana and Namibia to block certain agricultural imports.

African nations may well bask in the glory of being courted by superpowers as potential trade partners. And they may try to bargain hard, resisting undue influence by countries seeking to exert influence through trade regimes.

But adopting a tough negotiating posture alone will not enhance trade or regional economic integration. Triangulating between Russian, Chinese or American advances on the continent still leaves unattended Africa’s positioning for better trade terms. Its position is strongest only if African countries can bring the idea of a common market to fruition. That, in turn, would require commitments to good governance, a tall but not insurmountable order.

Scenarios

African states have varying degrees of institutional development, as well as political stability. It is thus natural that countries in the region will have varying appetites for participating in a common market, based on the benefits they perceive. Protectionism will repeatedly rear its head, as will suspicion that the economically strongest AfCFTA members seek to dominate the rest.

For weaker democracies still striving for postindependence stability, a common market appears threatening and potentially destabilizing for local politics. Demands for labor law reforms along democratic and human rights lines may also pose hurdles in some countries.

Given these challenges, the idea of free trade in Africa is not likely to be seen as a priority, and bilateralism may persist as the dominant approach in building trade relations for most countries in the region. It is an approach that has not brought positive results recently – especially for embattled democracies that embrace protectionism in response to social discontent over domestic policy failures.

Prospects for a genuine commitment to an African common market are not high. Nevertheless, free trade remains a necessary condition for integration on the continent, and for Africa to secure bargaining power in the changing global order. Individual countries that persist on the path of trade bilateralism will keep negotiating on uneven playing field.