Americans need a new debt ceiling again

Despite the bipartisan standoff, Republicans and Democrats will likely come to a last-minute agreement to lift the public debt ceiling beyond the current $31.4 trillion.

In a nutshell

- A compromise on revenue and spending is likely to emerge from talks

- Politicians have lost credibility because of repeated debt ceiling hikes

- An extended impasse threatens to cause serious economic damage

The threat of a default by the United States has made headlines again. Although the ratio of tax revenues to gross domestic product (GDP) has increased significantly during the 2020-2022 period, spending has risen faster than anticipated. Consequently, the budget deficit is running higher than expected and the Treasury might be short of cash in early June. Which constraints are U.S. policymakers facing and what could happen?

The crisis came because of poor forecasting on three fronts. This explains why the Treasury Department was already short of liquidity in January 2023, but decided to turn a blind eye and felt confident it could tread water until the end of the year. First, the U.S. government hoped that the post-Covid recovery would bring about much higher revenue. In fact, GDP growth in the U.S. went down from 2.6 percent (fourth quarter 2022) to 1.1 percent (first quarter 2023) and many believe that it will further decline in the near future. In other words, a recession has been averted for the time being, but this has not been enough to protect the federal budget.

Second, Wall Street did not perform according to expectations. In the past, stock performance originated generous capital gains, and thus capital-gain taxes. This is not the case today, since the S&P 500 Index declined 17 percent in 2022 and has bounced back only 7.7 percent during the past five months. Third, although government spending has declined relative to GDP, its size is up because of expensive social welfare programs and defense, as well as rising interest costs, which in 2022 rose 35 percent compared to 2021 and are expected to rise another 35 percent this year.

Repeatedly raising the debt ceiling

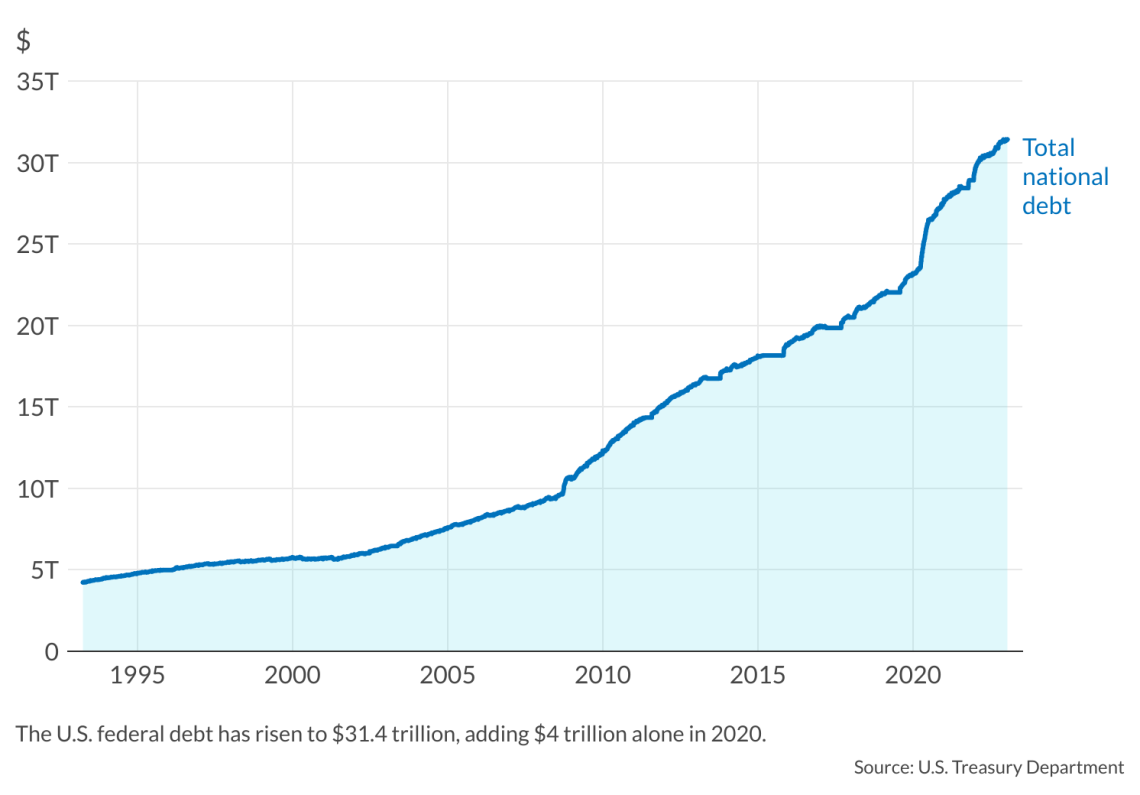

Of course, the current critical situation of the U.S. Treasury is not a matter of solvency, but of liquidity. The Treasury would have no problem if it were allowed to issue new bills and consequently obtain the funds required to meet its needs. Interest rates would inch higher, but only marginally. After all, the Joe Biden administration probably needs $200 billion to make it to the end of the year, a minor addition to the public debt of $31.4 trillion. However, President Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen need authorization from Congress to go beyond the current debt total. During the past decades, Congress frequently authorized increasing the debt ceiling under presidents of both political parties – at least 100 times in the last 82 years, according to USA Today. Will this time be different?

Not surprisingly, it is a matter of political expedience. The much-feared delayed payments regarding the U.S. public debt (interest and capital) are used as scarecrows. According to the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the Treasury must prioritize the service of the public debt (there is enough cash to do so), and then use the remaining liquidity to finance other spending. It is unlikely that the White House will want to engage in a long constitutional debate or suggest constitutional changes, which would be time-consuming and politically costly.

Facts & figures

The partisan battle over taxing and spending

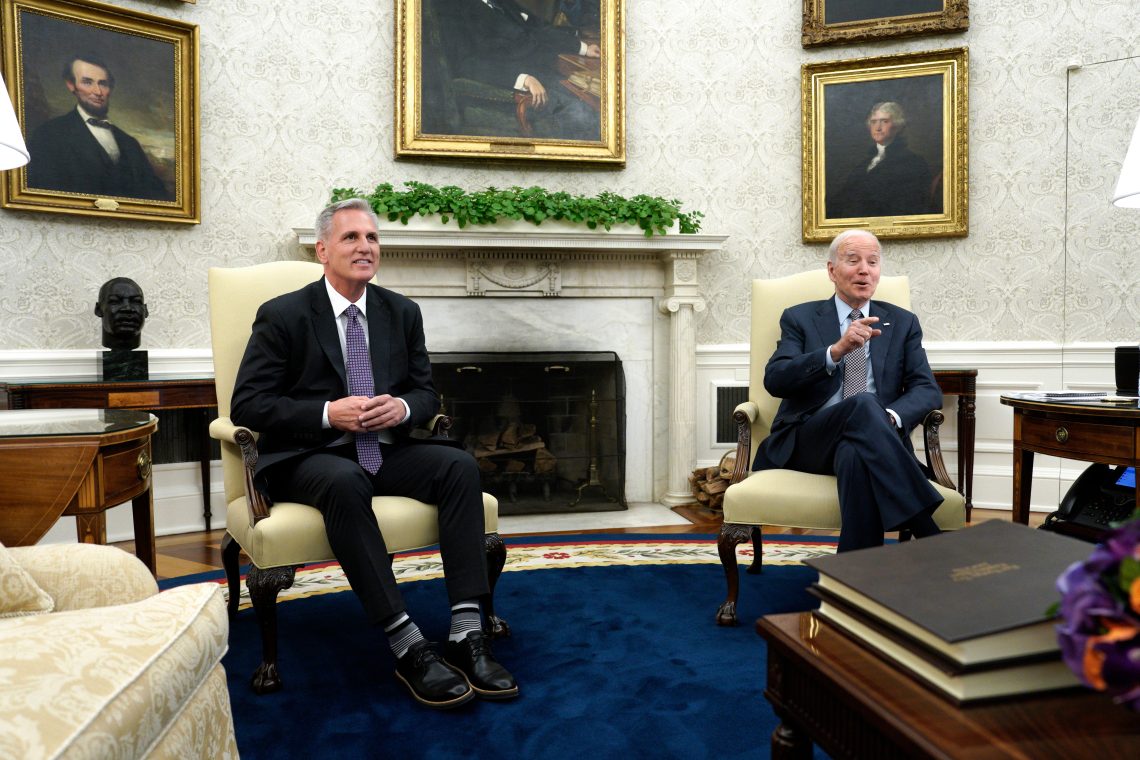

Yet neither Democrats nor Republicans want to back down. The Democrats have always maintained that the 2023 budget was sound and would respect the existing debt ceiling. Although presidential elections are less than 18 months away, Mr. Biden cannot admit he did not have the budget under control and cannot engage in serious budget cuts without alienating some of his voters. This explains why Democrats are only ready to agree on modest and temporary cuts to obtain the green light from Republicans in Congress. Republicans would lose face if they did not dig in and insist on a new budget with significant cuts and a commitment not to raise taxes.

Two dynamics stand out. First, neither Democrats nor Republicans would benefit from stopping payments, which would involve missed or reduced transfers to federal agencies and deferred payments of federal employees’ wages. Second, the positions of the two parties do not seem too far apart, and a compromise is feasible. For example, legislators could agree on moderating tax revenue rather than an outright freeze. Likewise, they could freeze rather than cut spending for some programs. If so, careful packaging of the deal would do the trick.

This judgment seems consistent with the sentiment prevailing on Wall Street, since the stock market would have already registered heavy losses if a debt moratorium (let alone a repudiation) was probable. It has not.

It is true that during May the yield on the one-month treasury bill moved from about 4.5 percent to about 5.5 percent. Yet, during the same period, the yield for three-month treasuries rose from 5 percent to 5.2 percent, while that for the five-year note went from 3.6 percent to 3.8 percent.

Put differently, markets do not fear the future and have not changed their expectations about the Federal Reserve’s commitment to fighting inflation. Rather, market operators fear that delays in reaching an agreement might disrupt their liquidity. The rise in interest rates signals greater uncertainty in the short term but does not mean that investors believe that disaster is around the corner.

Scenarios

Four scenarios lie ahead, in decreasing order of likelihood.

A quick agreement is reached that averts damage

First, policymakers will end up finding a face-saving compromise and agree on lifting the debt ceiling before early June, when the Treasury runs out of cash. Talks broke off on May 23

A slightly delayed agreement will harm America’s reputation

A second scenario would materialize if the Treasury does run out of cash, but Congress comes to the rescue relatively soon – say, by the end of June. In this case, financial markets would probably freak out for a couple of weeks, the image of America as a haven would suffer and domestic U.S. tensions would make headlines for months.

An extended impasse will cause major financial harm

A third possibility refers to a situation in which the current ceiling stays in place for several weeks, possibly months. Although the liquidity crisis might be over in July, as new tax revenues flow in, this would be the worst situation. American political institutions would lose public confidence, tensions and unemployment would rise significantly, and a new source of trouble would appear; commercial banking. While debt servicing would unlikely be threatened, the salaries of hundreds of thousands of federal employees would certainly be affected.

Since Americans usually run their budgets on a tightrope and rely heavily on consumer credit (60 percent of households do not have enough savings to cover more than three months of expenses), the enforcement of the current debt ceiling would encourage many households to borrow more. This would lead to a credit crunch and significantly higher interest rates. The administration might simply look the other way, or perhaps provide state guarantees or other forms of regulation to keep interest rates down and defuse tensions. If so, the temporary public finance crisis would open the way to further regulation. Put differently, a crisis triggered by the inability to manage public debt would become the vehicle through which more public debt is created in the future.

Simply remove the debt ceiling

A fourth scenario is the possibility that a prolonged stalemate leads to the removal of the debt ceiling. Until the early 20th century, all Treasury issues had to be authorized by Congress. The ceiling was introduced in 1917 to ease the procedures and ensure that war financing would not fall victim to congressional bickering. Although many thought it would be a temporary arrangement, it was left in place after the war was over.

Does it still make sense to have a ceiling that is raised every time politicians need more deficit spending? This pattern encourages book cooking by deliberately underestimating public spending and overestimating tax revenues. Certainly, the presence of the ceiling offers a veneer of rigor and restraint. Yet, that veneer has now lost much of its credibility, and one wonders whether it is worth the waves of uncertainty and petty logrolling that happens when the current ceiling becomes too tight.